The frightening reason violent EF-5 tornadoes are so rare

Less than one-tenth of one percent of all twisters are scale-topping behemoths

Hundreds of homes vanished beneath the black cloud that descended on May 20, 2013. The violent tornado that forever scarred Moore, Oklahoma, took less than ten minutes to carve from one side of town to the other.

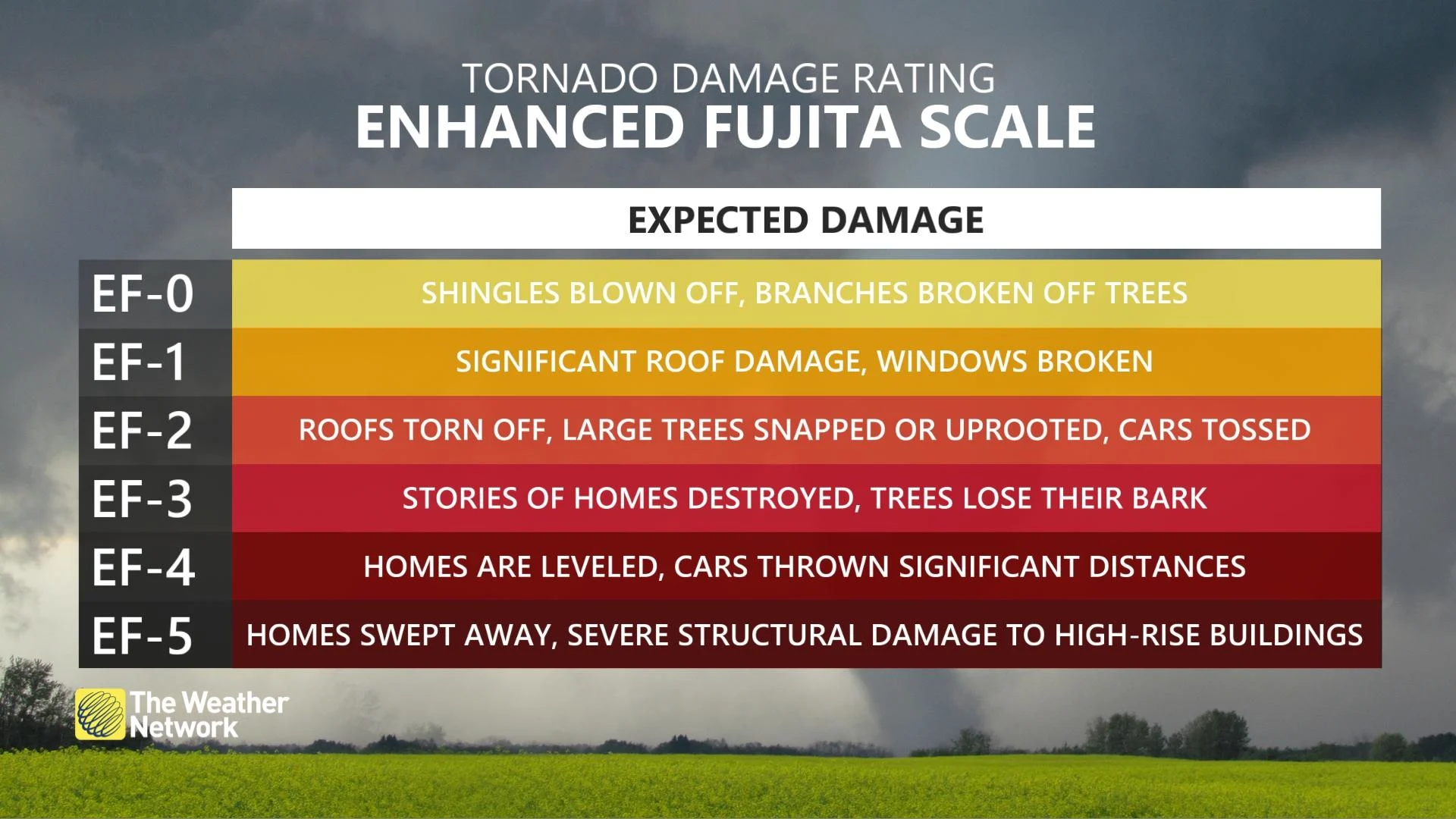

That devastating twister left behind EF-5 damage in its wake, the most severe category on the Enhanced Fujita Scale that uses damage to estimate a tornado’s winds.

And as of 2024, it’s the last tornado anywhere in North America to receive this scale-topping rating.

DON'T MISS: Don’t fall victim to these seven dangerous tornado myths

Plenty of tornadoes over the past decade have caused near-total destruction along their paths. In fact, it’s extremely likely that we regularly see tornadoes with winds of 323 km/h or stronger, but none have produced damage worthy of that EF-5 designation.

Here’s a look at how a tornado leaves behind EF-5 damage and why so few intense tornadoes ever manage to meet that terrifying level of destruction.

Ted Fujita’s scale formalized tornado investigations

Dr. Theodore Fujita developed the Fujita (F) Scale in the 1970s to rate tornadoes based on damage to buildings, vehicles, and vegetation.

Meteorologists and engineers introduced the revised Enhanced Fujita (EF) Scale in 2007 to incorporate extensive research into how different structures and objects withstand powerful winds.

Both scales range from F0/EF-0 (“weak”) to F5/EF-5 (“incredible”), with the top of the scale representing winds of 323 km/h or stronger.

WATCH: TWN's Jaclyn Whittal reports from the aftermath of the 2013 Moore tornado

F5/EF-5 tornadoes are very rare

The U.S. National Weather Service confirmed nearly 68,000 tornadoes across the country between 1950 and 2022. Tornado data is far more sparse in Canada, where Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Northern Tornadoes Project have confirmed more than 2,500 touchdowns since 1980.

MUST SEE: Tornadoes can happen anywhere—and cities aren't immune

Out of all those tornadoes, only 60 (0.085 percent) have ever been rated an F5 or EF-5. 59 of those tornadoes touched down in the U.S., with Canada's sole F5 twister hitting Elie, Manitoba, on June 22, 2007.

That’s an exceptionally small number—and it’s not just because violent tornadoes are particularly uncommon.

Tornadoes are rated based on damage

EF-Scale ratings are assigned based on damage, not actual wind speeds. Crews are trained to assess rubble based on more than two-dozen grading rubrics to help surveyors estimate wind speeds based on damage to everything from oak trees to skyscrapers.

A convenience store with EF-3 damage in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, on March 24, 2023. (NWS)

If a convenience store were destroyed except for small interior rooms like a closet or bathroom, winds there probably reached about 222 km/h. This level of damage would likely warrant an EF-3 rating.

STAY SAFE: Watch? Warning? How we communicate severe weather in Canada

Just one week after the Moore tornado in May 2013, the widest tornado ever recorded touched down in nearby El Reno. A mobile Doppler radar measured winds of nearly 475 km/h in the 4.2-kilometre-wide twister.

Despite the hard data that would suggest it was an EF-5, the storm only caused EF-3 damage to a metal structure and steel electrical power poles, so the tornado officially stands in the books as an EF-3.

WATCH: The science behind the EF-Scale

Few buildings can withstand an EF-4, let alone an EF-5

It’s likely that many tornadoes pack winds capable of producing EF-5 damage, but they don't cause the damage needed to earn that rating.

The long-track tornado that destroyed Mayfield, Kentucky, on December 21, 2021, is a grim example of the limits of using damage to estimate a tornado’s maximum winds. Meteorologists assigned the tornado an EF-4 rating with estimated winds just a tick below EF-5 strength.

Renowned wind engineer Tim Marshall noted in a post-storm report that “the tornado damage rating might have been higher had more wind resistant structures been encountered.”

EF-4 tornadoes often scrub buildings down to their foundation. It’s extremely difficult for meteorologists to find evidence of EF-5 damage because most structures and objects can’t stand up to that kind of sheer force.

Experts rely on unique and subtle clues for EF-5 ratings

If few buildings can stand up to those intense winds, then how do experts find evidence of these scale-topping twisters?

A home wiped from its foundation in the EF-5 Moore, Okla., tornado on May 20, 2013. (NWS)

For example, the above photo shows damage from the 2013 Moore tornado.

Surveyors note that this was a well-built house that was properly anchored to its foundation with bolts. The experts found those bolts were sheared by the intense winds within the tornado and used that evidence to assign an EF-5 rating.

RELATED: ‘This is a tornado emergency’: How forecasters warn of grave danger

Many of the damage indicators needed to achieve a scale-topping rating are subtle and based on context clues. One of the deadliest tornadoes in modern history was the EF-5 that killed more than 150 people in Joplin, Missouri, on May 22, 2011.

The worst-hit neighbourhoods were completely levelled by the storm. Street after street of total destruction mostly amounted to EF-4 damage. Experts largely relied on context clues to arrive at the storm’s rating, including that some vehicles were tossed long distances and shredded beyond recognition.

Heavy damage at the St. John's Regional Medical Center in Joplin, Missouri, May 2011. (Wikimedia Commons)

Another unconventional indicator experts used was the fact that the nine-storey St. John's Regional Medical Center was irreparably damaged after the tornado shifted and rotated the entire building on its foundation.

High-end, destructive tornadoes happen every season. Many of them are likely to produce unfathomably strong winds. Whether they hit anything capable of withstanding such intense forces, though, is a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.