Why Toronto's Don Valley Parkway floods so often

It seems like it's always 'that time of year' along the DVP.

It's almost a "classic" Toronto experience these days.

How many times have we seen this scenario play out? A particularly strong rainstorm washes over the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), with a concentrated heavy downpour drenching the east end of Toronto. Suddenly, commuting along the Don Valley Parkway goes from simply slow to downright hazardous as the Don River crests its banks and envelopes the traffic artery's south end.

The Don Valley Parkway flooded following a storm on May 29, 2013. Courtesy: The Weather Network

The answer to the above question: Too often.

In fact, imagine setting up H.G. Wells' famous time machine on the edge of the Don Valley and sending yourself back through history. As the City of Toronto dwindled around you, as you witnessed the Mississaugas, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples before them inhabit the area, and going all the way back to the last time the glaciers retreated from southern Ontario, roughly 12,000 years ago, you would see the Don River flood parts of the valley, again and again.

So, what exactly makes the DVP so prone to flooding?

Basically, it comes down to a combination of three things. First, it was simply geology and hydrology. Then, over the past 225 years or so, urban development has been incrementally adding to the problem.

The Don River, which is currently about 15 metres wide, is quite small compared to the 400-metre-wide Don Valley. However, the river and its precursors (possibly a collection of smaller streams, or maybe even a larger lake) played a key role in the valley's formation by carving it out of the local landscape.

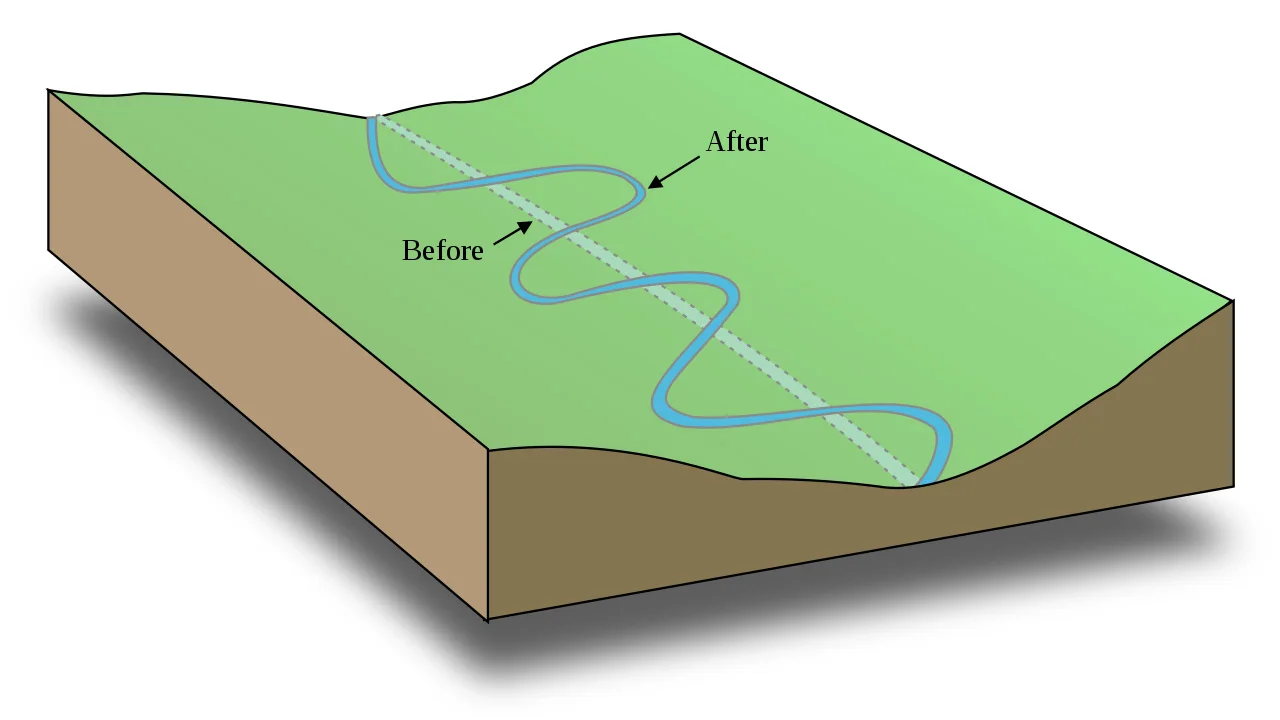

As water flows through a river, the current cuts into the sediments along the banks. The displaced sediments are then carried along, being deposited farther downstream or washed out into a larger body of water, such as a lake. Over time, this changes the shape of the river. It weaves back and forth in ever-widening curves, bends and loops, then breaks through some of those loops to form straight paths again, in a process called 'meandering'.

This diagram shows a simplified view of the meandering of a river's course over time. Credit: USDA/Mysid/Wikimedia Commons

The specific landscape the Don Valley was carved out of is composed of what's known as glacial till. Till is a loose mixture of clay, pebbles, stones, and boulders, which was once trapped in glacial ice and then deposited on the ground when the ice melted. Due to its nature, this type of loose topsoil is easily altered by flowing water, especially in the early days when it was first deposited.

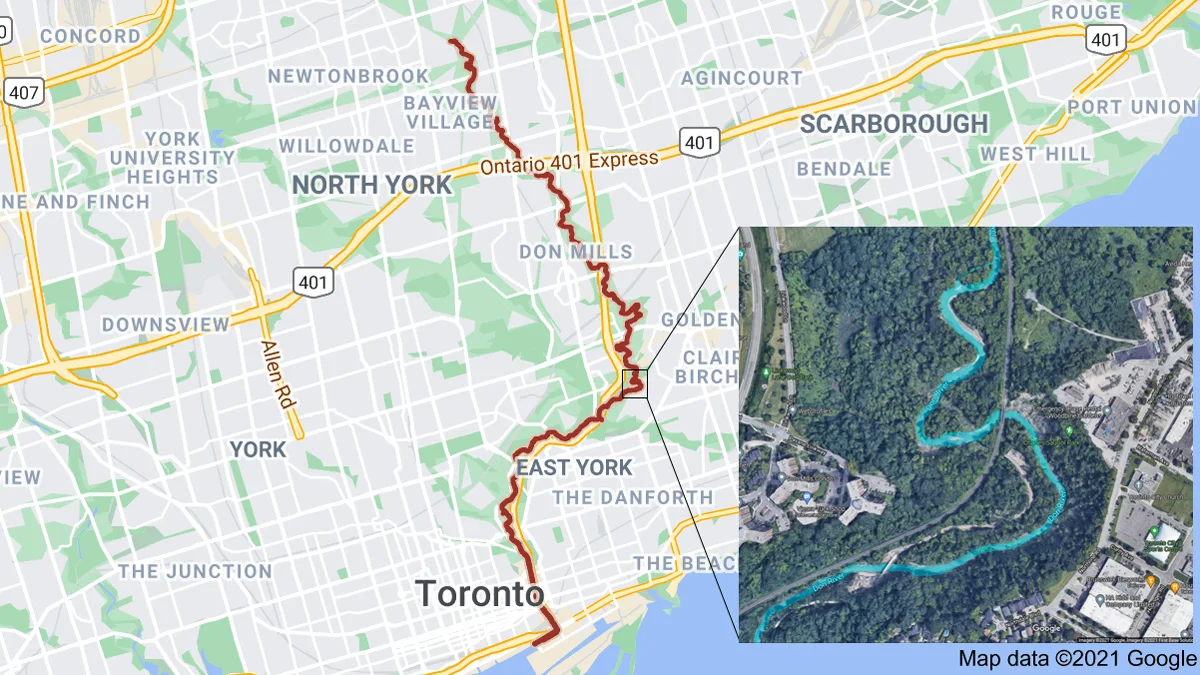

So, the flow of the Don River was likely fairly straight when it first formed (possibly as straight as it has been artificially made to be in some places now). The natural processes discussed above then caused its path to meander over time. Thus, over hundreds of years, the river cut back and forth across the valley.

This map shows the current course of the Don River. The inset satellite image shows a few of the river's remaining meanders, with the river highlighted in blue to more clearly show its path. Credit: Google/Scott Sutherland

Now, depending on what it's made of, the ground can only absorb so much water at one time. Sandy topsoil has relatively large individual particles and larger spaces between them, so it absorbs more water and it can absorb water fairly quickly. However, if there is more clay in the soil, the finer grains provide less space between them, resulting in less water absorption and thus slower removal of surface water.

No matter what the natural soil type, though, they allow at least some water absorption. Thus, they provide a natural buffer, to slow the transfer of rain water from where it falls to where it would enter the flow of any rivers and streams in the area. So, normally, waterways tend to handle the influx of water fairly well. Flooding typically occurs during extreme events.

In 1886, when the city adopted the Don Improvement Plan, construction teams dug out a long trench that cut through several of the meanders at the south end of the river. They then filled in all the twists and turns of the river with dirt, effectively deepening and straightening that section of the waterway. This helped with the immediate issue of overland flooding.

It was Hurricane Hazel, which blasted across Toronto in 1954, that served as an effective wake-up call for the disaster potential that still existed in the valley. River flows during the storm have been estimated at around 1,700 cubic metres per second — over 400 times greater than the normal average flow the river experiences.

There hasn't been anything quite that bad since. However, the government did ban development in the valley (as well as other flood plains) as a result of that disaster.

Still, less than four years later, in 1958, construction crews broke ground on the newly approved Don Valley Parkway, which was going to wind its way right through the middle of the Don River's flood plain.

Meanwhile, the city continued to grow, laying down even more concrete and asphalt, up and down the lands that border both sides of the river valley. These artificial surfaces are specifically designed to minimize water penetration, to improve their durability and strength. Therefore, rainwater or meltwater just flows along the top until it reaches a storm drain. Storm drains, for their part, are effective at moving that water along, to prevent it from becoming a problem where it originated. However, this just passes the problem along.

As the water flows along in storm sewers, it multiplies as more is gathered by each storm drain located along the sewer's path. Compounding the problem is the fact that, in older sections of Toronto, many underground sewer lines that collect water from people's homes combine together with storm sewers. The result is a large, rapidly moving volume of water that flows into the Don River, which can far exceed what the waterway can normally handle.

Urban development is also influencing this in another way, due to the urban heat island effect. This effect is the result of the concentration of artificial surfaces in urban areas, which causes a localized increase in temperatures (especially at night). Some studies have noted this may be resulting in a localized increase in precipitation amounts over cities like Toronto.

Climate change may be having its own impact on these trends, as well. Increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere cause temperatures to increase. That's been a well-established scientific fact since the 1800s. Also, warmer air is capable of holding more water vapour than cooler air, and it will fill that capacity from any source of water available (the ground, lakes, rivers, oceans, etc). With an increased amount of water vapour in the air, this translates into greater water availability to form clouds and precipitation. Thus, due to climate change, there is an increased chance that storms will produce higher rainfall rates.

Watch below: The Science Behind Flash Flooding

Is this going to get any better?

Toronto and Region Conservation Authority staff work very hard on flood management, of course.

In recent years, a fairly aggressive flood management plan (pdf) was put into place for the south end of the Don Valley, sparking off major excavation and construction to try to deal with the problem. However, even as of April 2014, both the Lower Don and Brickworks regions of the Don River — both of which border the last stretch of the Parkway before it merges with the Gardiner Expressway — were still identified as 'flood vulnerable areas' on Toronto and Region Conversation Authority maps (pdf).

Newer projects, such as the Don River and Central Waterfront & Connected Projects, and the related Wet Weather Flow Master Plan, are the latest attempts to address the problems with the Don River.

Although much of these plans appear focused on water quality, mainly by separating the cities combined sewer systems, there are aspects of them that could have a direct impact on flooding. In particular, the Coxwell Bypass Tunnel is intended as a way to capture combined sewer flow, as well as storing it during extreme rainstorms. By storing it, this will reduce the overall amount of water entering the river at once, thus reducing the chance of flooding. The plan is then to transport this stored water to a water treatment plant once flow rates in the system return to normal.

Other ways of addressing the problem include daylighting. As the city has grown, many of the natural streams and creeks that run through the area have been preserved, but now run through artificial environments — metal pipes and concrete sewers that keep the water from being absorbed by natural soils. Daylighting returns these streams and rivers to a more natural state, allowing more water to soak into the ground, thus restoring part of that natural buffer for the river.

Also, technology can help as well as hinder, like the development of a new product called Topmix Permeable, by British company Tarmac, which has been nicknamed "Thirsty Concrete."

Simply by replacing the fine grain materials of the concrete mix with coarse grains of crushed granite, Tarmac has produced a porous version that emulates how sandy soils respond to rainfall. According to the company, this concrete can deal with a flow rate of up to 36,000 millimetres per hour. That's over 700 times better than what sand can handle, and somewhere around 2,000 times better than the permeability of your average soil. For comparison, on July 8, 2013, when 126 mm of rainfall caused extensive flooding throughout the GTA, it fell mostly over a two-hour period. However, that doesn't even come close to what this new concrete can handle.

Perhaps, as the city continually repaves Toronto's roadways, a slow replacement of fine-grain impermeable concretes with coarse-grain permeable ones, along with preservation of green-space and an expansion of the daylighting process, could help enough to eventually bring this problem under control.