After a bright fireball, meteorites may have hit the ground east of Lake Simcoe

A space rock dove into Earth's atmosphere on Sunday night, and pieces of it may have survived to reach the ground.

This may sound like a science fiction movie pitch, but it's true: tiny visitors from outer space may have crash-landed in Central Ontario on Sunday night.

At 11:37 p.m. on April 17, a bright fireball lit up the night sky just north of Toronto. As of Tuesday morning, over two dozen witnesses have reported the event to the American Meteor Society, from as far away as Ann Arbor, MI, and Albany, NY.

Its passage was much too fast for these witnesses to capture it on video. As luck would have it, though, this fireball passed over several cameras in Southern Ontario that are set up expressly to watch for these kinds of events.

According to Western University News, meteor scientist Denis Vida said that the fireball was captured by over a dozen all-sky cameras in the university's Southern Ontario Meteor Network (SOMN). In addition, several citizen scientist-operated cameras from the Global Meteor Network (GMN), a group led by Vida, also recorded footage of it.

Watch below: Global Meteor Network citizen scientists Tim Claydon and Miguel Preciado caught these views of Sunday night's meteor

SO WHAT WAS THIS?

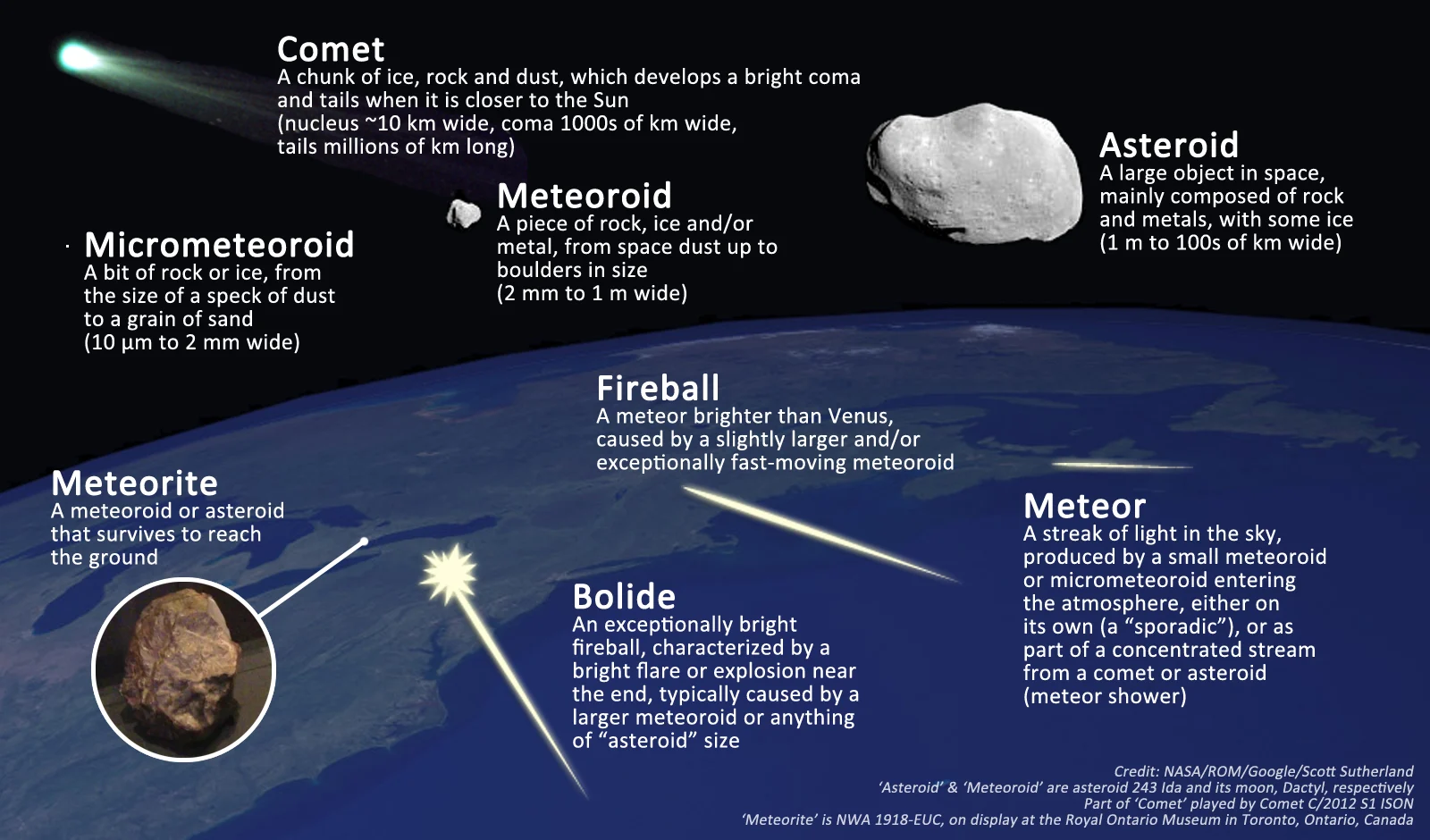

Meteors and fireballs are caused by bits of dust, rock, and ice — collectively called meteoroids — which have been floating around in space for up to 4.5 billion years. When their paths intersect with Earth's orbit, these objects plunge into the atmosphere at high speed. Travelling anywhere from 10 to 70 kilometres per second, a meteoroid compresses the air in its path, turning it into a white-hot glowing plasma. This is the source of the meteor flash that we see in the sky.

As the meteoroid presses on the air molecules, they push back on it, causing it to slow down. It only takes seconds, but either the heat from the plasma vaporizes the meteoroid (for smaller ones), or pushback from the air slows the meteoroid down to the point where it can't maintain the plasma. Either way, that's when the meteor flash winks out. Any material that survives past that point enters what's known as dark flight. This is where what's left of the meteoroid falls to the ground under the force of gravity and can be potentially found as meteorites.

Whenever a fireball like this is sighted, meteor scientists are presented with a challenge — exactly how much information can you glean from just a few seconds' worth of video footage?

However, since this meteor was recorded by multiple cameras, spread out over a wide area, each from a different point of view, they can actually learn quite a bit. For example, they can gauge the speed of the meteoroid and the brightness of the meteor flash it produced. This can give them a reasonably accurate estimate of the meteoroid's mass.

In this case, Vida told Western U News that the space rock's mass, before it hit the atmosphere, is believed to be around 10 kilograms. Meteoroids tend to be fairly dense compared to native Earth rocks. On average, a 10-kg meteoroid would be about 15-20 centimetres across or roughly the size of a softball.

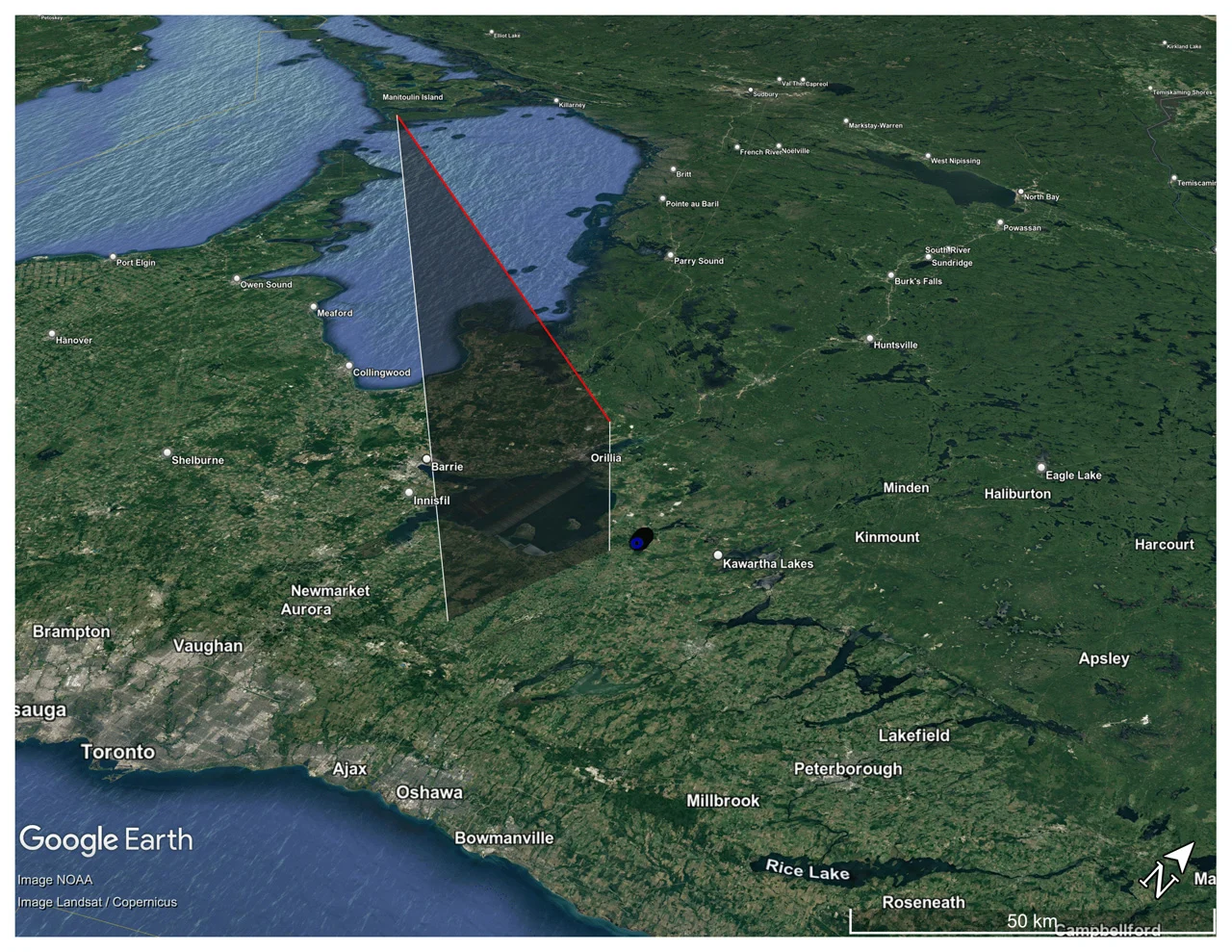

This trajectory (red arrow) was produced by analyzing data from WesternU's all-sky meteor camera network. Credit: Denis Vida/Western University

The multiple vantage points also allowed them to pinpoint the meteoroid's path. This revealed that it dove in on a steep angle, first showing up at about 90 kilometres above the ground and still producing light at just 29 kilometres up.

Based on everything they learned, Vida believes that pieces of this meteoroid may have survived to reach the surface.

From that 10-kg initial mass, Vida said "we would expect tens to hundreds of grams of material on the ground."

The possible meteorite fall zone from the April 17, 2022 fireball. Credit: Denis Vida/Western University

Even better, the data collected from the meteor camera network narrowed down the most likely area where the meteorites would have fallen. It covers a thin patch of land to the east of Lake Simcoe, about 2 km long by 0.5 km wide, just to the northwest of Argyle, ON.

Watch below: The most pristine meteorite sample in the world is being housed in Canada, see it

A FEW THINGS ABOUT METEORITES

"Meteorites are of great interest to researchers, as studying them helps us to understand the formation and evolution of the solar system," Vida told WesternU News.

Finding meteorites is not an easy task. Depending on where you're looking, they may be concealed by trees, plants, and even other, more mundane rocks. As a result, it often takes luck and a keen eye to locate them. However, they do have a few characteristics that set them apart from native Earth rocks.

Magnetic — due to having a high metal content, most meteorites will stick to a magnet.

Fusion crust — the outer surface of a meteorite will have a very thin, glossy dark crust, anywhere from grey to brown to black, which is produced by the heat as the meteoroid travels through the air. By comparison, the interior will tend to have a lighter colour.

Shape — meteorites tend to be unevenly shaped and are only rarely spherical or symmetrical. However, due to their passage through the air, any sharp corners will have been rounded smooth.

Fragments — larger meteoroids frequently break apart on their pass through the atmosphere. Thus, they are usually found as irregularly-shaped fragments, with only one side showing the smoothed shape and fusion crust.

Interior — there are three basic types of meteorites, each with a different appearance on the inside, with 'iron' meteorites shiny like steel, 'stony-iron' being steel-like with small gemstone-like bits embedded within, and 'stony' mostly uniform or with tiny spherules all packed together.

Regmaglypts — some larger meteorites, especially iron ones, will have impressions on their surface, which look similar to a thumbprint pressed into putty.

These three fragments of the carbonaceous chondrite Tagish Lake meteorite were collected from northern British Columbia in January 2000. These examples show off the dark fusion crust, in contrast to the lighter interior visible in a few surface patches. Photo provided by Chris Herd, University of Alberta.

Also, beware of so-called meteor-wrongs.

Many Earth rocks, both natural and artificial, can share some of these characteristics. For example, hematite and magnetite, as well as mining and industrial slag, are commonly mistaken for meteorites due to their magnetic properties. The biggest flags to identify a meteor-wrong are if it's not magnetic, lacks a fusion crust, has tiny holes in the surface, or looks like it's made up of layers.

There's another vital factor to remember before you go meteorite hunting. While meteorites can be freely collected from public land, always ask permission before venturing onto someone's private property to search for rocks from space.

It's the courteous thing to do, but by Canadian law, the private owner of the land a meteorite falls onto also owns that meteorite. So, be sure to ask permission and also discuss — up front — who gets to keep what you may find.

For anyone who goes looking for meteorites from this event, bring along some aluminum foil and plastic bags. Don't worry. This isn't due to any safety concerns. Meteorites are very safe to handle, even immediately after hitting the ground. However, by wrapping what you find in foil and placing them in clean plastic bags, you can help preserve their scientific value.

If anyone believes they've located one or more meteorites from this fall, take 2 or 3 good pictures of what you've found, and send them to the scientists at the Royal Ontario Museum.