Peregrine Moon mission ends Thursday as a fireball over the South Pacific

With this first private lunar lander unable to safely reach the surface of the Moon, it instead ended its mission here on Earth, late Thursday afternoon.

With their ailing lunar lander unable to fulfill its directive to touch down on the Moon's surface, Astrobotic ended Peregrine's mission by burning up in Earth's atmosphere.

This story has been updated with details on the re-entry and subsequent burn-up of the Peregrine lander in Earth's atmosphere, as well as the issues regarding the human and animal remains on board the spacecraft.

On Monday, January 8, 2024, the first private space mission to the Moon lifted off from NASA's Kennedy Space Center. Although the rocket launch that carried Astrobotic's Peregrine Mission One into space was picture-perfect, once it reached orbit, something went very wrong.

Astrobotic's Peregrine lander lifts off atop the first ULA Vulcan rocket to launch, in the early morning of Monday, January 8, 2024. Credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Shortly after separation from the booster, Astrobotic's first mission update reported an 'anomaly' which kept Peregrine from orienting itself properly so that its solar panels could face the Sun.

Subsequent updates identified the problem as a "critical loss of propellent."

Simply put, the lander was losing fuel due to a failure in Peregrine's propulsion system. This leak was not only the cause of the spacecraft's problem with maintaining the proper alignment to gather power. The rate of the fuel loss also doomed Peregrine's mission to set down on the Moon's surface. There was no way that the spacecraft would have enough left for a soft landing.

This image of Peregrine's payload deck, taken on January 15, 2024, by a camera attached to the deck, reveals what the mission team called a "disturbance" in the Multi-Layer Insulation that makes up the lander's outer hull. Credit: Astrobotic

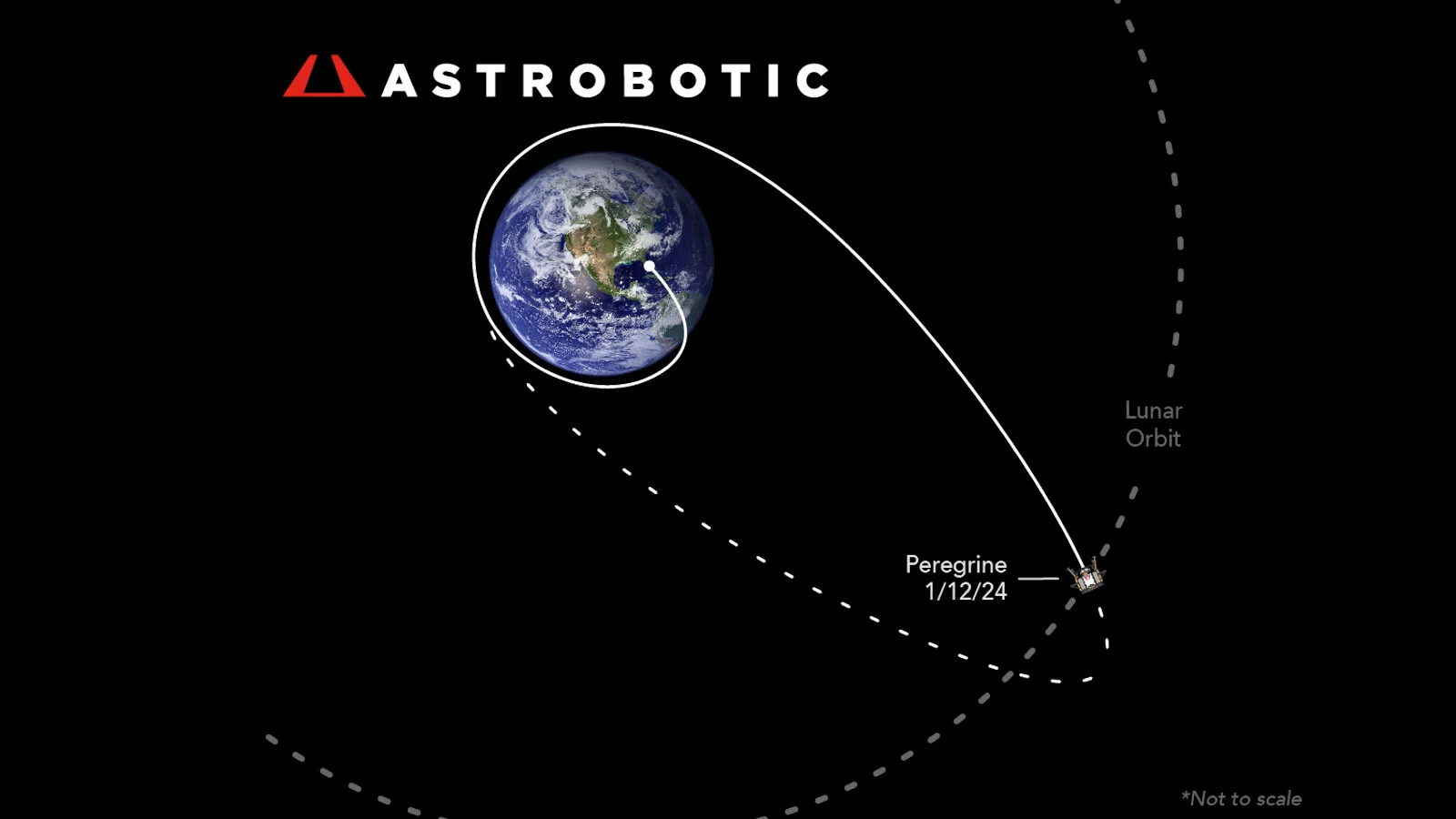

Over the past week, Astrobotic has kept Peregrine stable and fully powered as the spacecraft reached lunar orbit — at 384,000 km out — and began its journey back toward Earth.

This followed Peregrine's original flight path, which was set to have the spacecraft arrive at lunar orbit before the Moon actually reached that point in space. Peregrine would then loop back around Earth once, before returning to lunar orbit to rendezvous with the Moon on day 15 of the mission.

From Astrobotic's January 12 update, this diagram shows Peregrine having reached lunar orbit in its flight path. Although the graphic shows that the Moon was not at that location in its orbit when Peregrine passed that point, it would have been there upon the lander's return. Credit: Astrobotic

The mission team even activated several of the science instruments on board to gather as much information about Peregrine's operations as possible.

"Measurements and operations of the NASA-provided science instruments on board will provide valuable experience, technical knowledge, and scientific data to future CLPS lunar deliveries," Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration with NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said in an update.

However, with no chance of successfully making a soft landing on the Moon, Astrobotic had a difficult decision to make. If Peregrine were to be left alone to continue along its orbit, it could become a hazard to other missions. This includes the potential for a collision with a satellite in Earth orbit during each pass by the planet, as well as a possible crash into the Moon or with any lunar-orbiting spacecraft such as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or the future Lunar Gateway Station.

Thus, in their January 14 update, the company announced that they will follow the recommendation given to them by NASA, the United States government, and the space community.

"The recommendation we have received is to let the spacecraft burn up during re-entry in Earth's atmosphere," the mission team wrote. "Since this is a commercial mission, the final decision of Peregrine's final flight path is in our hands. Ultimately, we must balance our own desire to extend Peregrine's life, operate payloads, and learn more about the spacecraft, with the risk that our damaged spacecraft could cause a problem in cislunar space. As such, we have made the difficult decision to maintain the current spacecraft's trajectory to re-enter the Earth's atmosphere. By responsibly ending Peregrine's mission, we are doing our part to preserve the future of cislunar space for all."

According to Astrobotic, they continue to monitor the spacecraft's trajectory for its controlled re-entry into Earth's atmosphere. They do not believe that this re-entry poses any safety risks, and it should result in Peregrine completely burning up in the atmosphere.

"I am so proud of what our team has accomplished with this mission. It is a great honour to witness firsthand the heroic efforts of our mission control team overcoming enormous challenges to recover and operate the spacecraft after Monday's propulsion anomaly," said Astrobotic CEO John Thornton. "I look forward to sharing these, and more remarkable stories, after the mission concludes on January 18. This mission has already taught us so much and has given me great confidence that our next mission to the Moon will achieve a soft landing."

Burning up over the South Pacific

In a Wednesday update from Astrobotic, the company confirmed that they have placed Peregrine on course to re-enter Earth's atmosphere over the southwestern Pacific Ocean, around 1,300 km to the north of New Zealand.

This location was chosen "to minimize the risk of debris reaching land," the company said.

This graphic shows a map of the region where Peregrine is expected to burn up. As noted at the bottom, this result was produced based on the spacecraft's trajectory and speed as of 4:30 p.m. EST on Wednesday, January 17. At the time, Peregrine was 223,700 km away from Earth, or roughly 60 per cent of the distance to the Moon's orbit. Credit: Astrobotic

Due to the damaged propulsion system on Peregrine, the mission controllers used a two-step plan to put the spacecraft on the right trajectory to reach this final re-entry point. First, a series of 23 short burns of its main engine, carefully timed to avoid further damage to the system, put it on the right course. Second, since the leaking propellent was still exerting its own small but persistent push, they rolled the spacecraft to precisely aim the leak so that its push would shift Peregrine into the exact reentry ellipse shown above.

The mission team expects the timing of the re-entry to be around 4 p.m. EST, on Thursday, January 18.

Update

Richard Stephenson, who works at NASA's Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, confirmed in a post on X that Peregrine Mission One ended at 20:59 UTC (3:59 p.m. EST), on target and on schedule with Astrobotic's predictions.

NASA and Astrobotic will co-host a live teleconference on NASA TV at 1 p.m. EST, Friday, January 19, to discuss the mission and its end.

Science and Memorials lost

Once Peregrine burns up the science instruments installed on the lander by NASA will be lost:

LETS (Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer), which was to study the radiation astronauts would experience on the lunar surface,

NIRVSS (Near-Infrared Volatile Spectrometer System) for studying lunar soil temperature and structure,

NSS (Neutron Spectrometer System) for passive detection of water in the lunar soil, specifically from the lander's engine exhaust,

PITMS (Peregrine Ion-Trap Mass Spectrometer) for studying the composition of the thin lunar atmosphere, and

LRA (Laser Retro-Reflector Array) which is a collection of eight retroreflectors that can be used by spacecraft to gauge their distance to the lander.

This rendering of the Peregrine lunar lander shows an artist's conception of the spacecraft on the Moon's surface, ready to deploy its science instruments. With future missions in the works, a small lunar lander may provide us with a real version of this soon. Credit: Astrobotic

Also lost will be Celestis' Tranquility Flight, a "memorial spaceflight" holding the ashes or DNA samples of 66 "participants" - avid science fiction fans, space enthusiasts, inspiring educators, authors, beloved pets, scientists, spaceflight engineers, and others who would have appreciated some small piece of them making the journey to space. The ashes of scientist and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke were also on board, as well as those of Gene and Majel Roddenberry.

Another memorial flight, known as Elysium Lunar 1, was also flown on Peregrine by private company Elysium Space. Although there appear to be no specific details made public about whose remains were on board, images posted to the company's Flickr photostream indicate that there were the remains of at least 25 people on the flight.

The inclusion of these remains on the spaceflight caused some controversy leading up to the launch date. Objections were raised by the Navajo Nation to the mission, due to concerns that it would desecrate a place held as sacred to many Indigenous cultures.

"It is crucial to emphasize that the Moon holds a sacred position in many Indigenous cultures, including ours," Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren wrote in a letter to NASA and the U.S. Department of Transportation. "We view it as a part of our spiritual heritage, an object of reverence and respect. The act of depositing human remains and other materials, which could be perceived as discards in any other location, on the Moon is tantamount to desecration of this sacred space."

This is the second time objections have been raised by the Navajo Nation to human remains being sent to the Moon. The first was in 1998, regarding NASA sending the ashes of geologist Eugene Shoemaker to the Moon on the Lunar Prospector mission. Shoemaker studied meteorite impact craters, produced the first geological map of the lunar surface, and co-discovered Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which hit Jupiter in July 1994.

As Alvin D. Harvey, a member of the Navajo Nation currently completing their PhD in Aeronautics and Astronautics at Cambridge University, wrote on Nature.com earlier this week: "Nygren's call to action is not about ownership of the Moon or to enforce Diné religious beliefs, but rather about the right to be consulted, to uphold Native American legal rights, to hold government agencies accountable and to safeguard the Moon for future generations."

Indeed, the United States government has agreements in place that specify it must consult with Indigenous tribes when the spaces held sacred by those peoples could be impacted. While Peregrine was a private spaceflight mission and thus the cargo included was not entirely up to NASA, the space agency (and thus the U.S. government) did have a large financial stake in the mission.

At this moment, there is no specific set of rules governing the use of the Moon or any other celestial body.

The Outer Space Treaty, which has been in effect since October 1967, prohibits the deployment or use of nuclear weapons in space, designates that the Moon and all other celestial bodies are to be used for peaceful purposes, establishes that space can be explored and used freely by all nations of the world, and prevents any nation from claiming sovereignty over outer space or any celestial body.

The Moon Treaty, which was drafted in 1979, has the stated objective "to provide the necessary legal principles for governing the behavior of states, international organizations, and individuals who explore celestial bodies other than Earth, as well as administration of the resources that exploration may yield." However, since the treaty has not been ratified by any nation that currently conducts space launches, it holds no authority.

With the failure of Peregrine Mission One, the remains included on board will not reach the Moon. With private space missions becoming more common now, it may be a good time to review how their activities relate to the agreements already in place, and for us to decide if there should be limitations on the commercialization of space and the Moon.

(Thumbnail image combines an artist rendition of the Peregrine lunar lander, courtesy Astrobotic, with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter recreation of the Apollo 13 Earthrise via NASA. On the right is the reentry of the ATV-1 European satellite, which was de-orbited over the Pacific Ocean on September 28, 2008, courtesy NASA and the ESA.)