'Hidden' cache of water ice may have been found in Mars' Grand Canyon

Spotted by the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, this ice deposit appears to lie just under the surface, making it a potential resource for future Mars explorers.

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter has made a remarkable discovery. There appears to be a large deposit of water ice, roughly the size of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined, lying just under the ground in Mars' Grand Canyon.

Valles Marineris is an immense canyon that stretches across the surface of Mars near its equator. At over 4,000 kilometres long, 200 kilometres wide, and up to 10 kilometres deep, it is roughly 10 times the length and 5 times the depth of Earth's Grand Canyon. And up until recently, it was 'hiding' a valuable resource — significant amounts of water, apparently lying just beneath the surface in the deep valleys of the feature known as Candor Chasma.

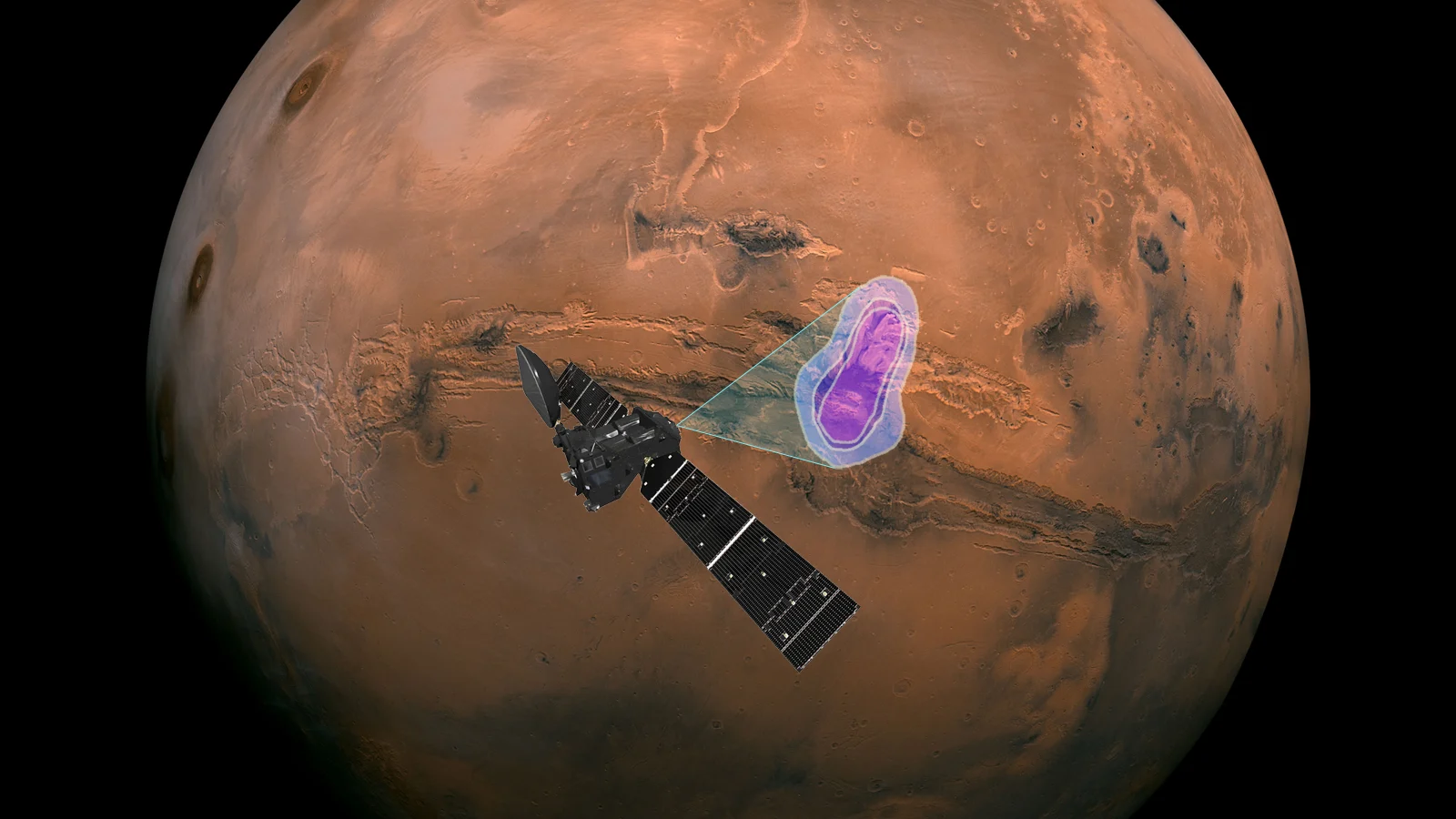

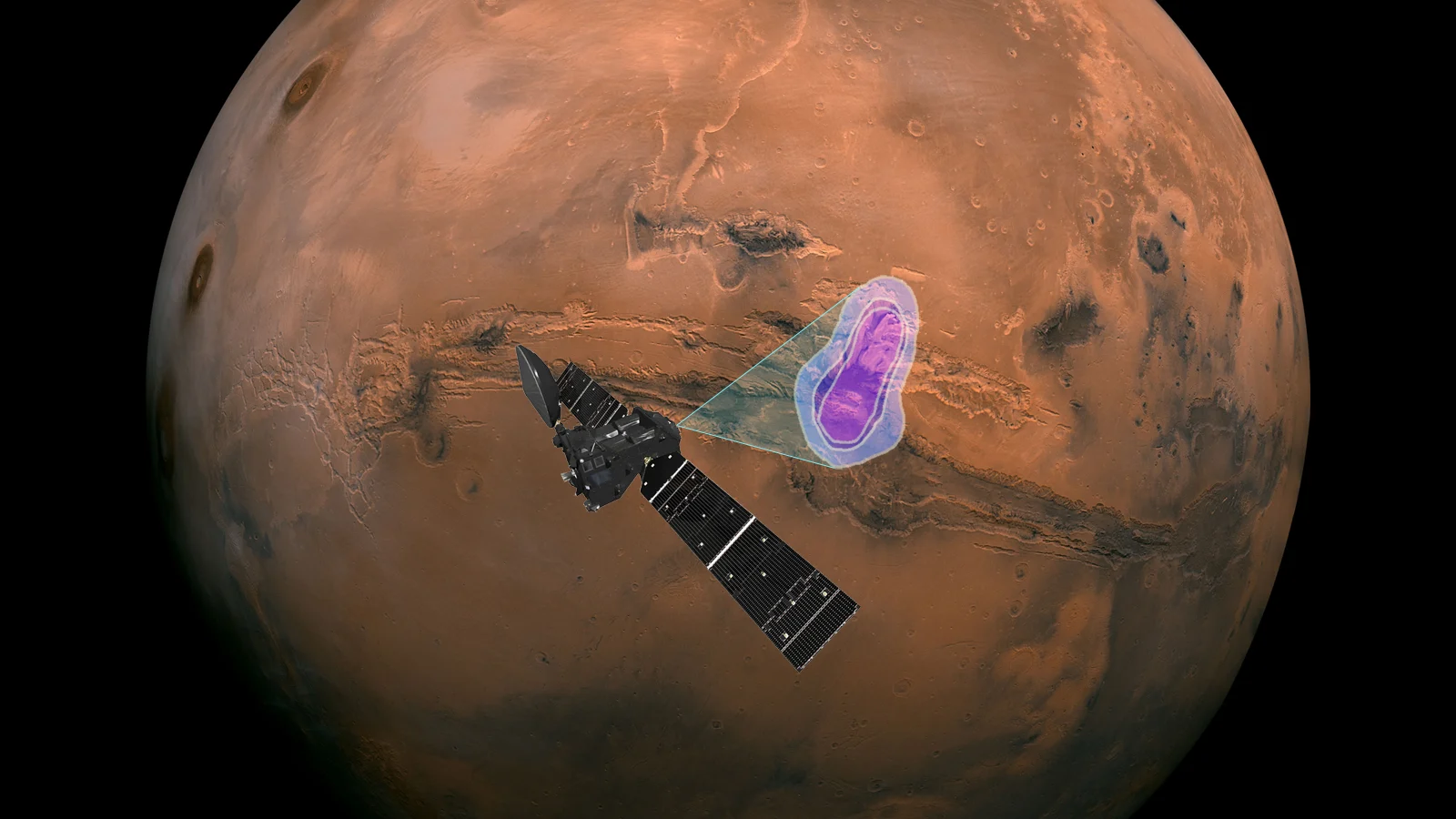

This mosaic image of Mars from space, composed of pictures from the Viking orbiter, shows the immense canyon system called Valles Marineris. Overlaid is a computer rendering of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter spacecraft and data from the ExoMars orbiter showing the location of a possible water deposit. Credit: NASA/ESA/Scott Sutherland

This discovery was made using data sent back from the FREND instrument (Fine-Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector), on board the ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft. FREND detects neutrons produced when high-energy cosmic rays strike the surface of Mars. As these particles can penetrate the top layers of the ground, they affect minerals and deposits below the surface dust. By analyzing the data FREND collects, scientists can determine what may be hiding under that dust.

"With TGO we can look down to one metre below this dusty layer and see what's really going on below Mars' surface — and, crucially, locate water-rich 'oases' that couldn't be detected with previous instruments," FREND principal investigator Igor Mitrofanov, of the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in an ESA press release.

"FREND revealed an area with an unusually large amount of hydrogen in the colossal Valles Marineris canyon system: assuming the hydrogen we see is bound into water molecules, as much as 40 per cent of the near-surface material in this region appears to be water," Mitrofanov explained.

Finding water with FREND is a case of looking at what isn't there, apparently.

"Neutrons are produced when highly energetic particles known as 'galactic cosmic rays' strike Mars; drier soils emit more neutrons than wetter ones, and so we can deduce how much water is in a soil by looking at the neutrons it emits," study co-author Alexey Malakhov, also of the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said. "FREND's unique observing technique brings far higher spatial resolution than previous measurements of this type, enabling us to now see water features that weren't spotted before."

According to the ESA: This water could be in the form of ice, or water that is chemically bound to other minerals in the soil. However, other observations tell us that minerals seen in this part of Mars typically contain only a few percent water, much less than is evidenced by these new observations. Water ice usually evaporates in this region of Mars due to the temperature and pressure conditions near the equator. The same applies to chemically bound water: the right combination of temperature, pressure and hydration must be there to keep minerals from losing water. This suggests that some special, as-yet-unclear mix of conditions must be present in Valles Marineris to preserve the water — or that it is somehow being replenished.

This view of Valles Marineris, showing the feature at a 45-degree angle, was created using data from the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on board the ESA's Mars Express orbiter. Candor Chasma is the large valley just to the north of the main canyon. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

There have been many discoveries of water on Mars over the years — craters filled with water ice, lakes of brine under the south pole, and numerous glaciers buried underground.

While these findings are fascinating and show that Mars was, indeed, a much wetter place in its warmer past, there's something more significant about this discovery.

Much of the water found up until now has been in very remote regions of the planet's icy poles where we are less likely to send robotic missions, or it has been buried deep under the surface where we will likely never be able to drill deep enough to access it.

If TGO has discovered an abundant deposit of water ice in the deep valleys of Valles Marineris, it might turn out to be one of the best places to search for evidence of life on Mars. It could also be a potential resource for future human explorers.