What can we see in the night sky this Fall? Here are the season's top events

A rare transit of Mercury, plus meteor showers, planetary conjunctions and the elusive Zodiacal Light.

As the nights get longer, Fall is an excellent time of year to get out under the stars, and there are plenty of events to behold this season.

A number of minor meteor showers grace the sky in Fall, with the amazing Geminids meteor shower ending off the season in December. Saturn and Jupiter are still shining bright throughout the nights, even teaming up with the Moon for a few nights each month. The most spectacular event, however, will be the rare Transit of Mercury.

Read on!

FALL ASTRONOMY 2019

Sept 26-Oct 10: Zodiacal Light in pre-dawn eastern sky

Oct 3: Jupiter-Moon Conjunction

Oct 5: Saturn-Moon Conjunction

Oct 8: Draconids Meteor Shower peak

Oct 10: Southern Taurids Meteor Shower Peak

Oct 13: smallest/dimmest Full Moon of 2019

Oct 21: Orionids Meteor Shower peak

Oct 26-Nov 9: Zodiacal Light in pre-dawn eastern sky

Oct 31: Jupiter-Moon Conjunction

Nov 2: Saturn-Moon Conjunction

Nov 5: Northern Taurids Meteor Shower peak

Nov 11: Transit of Mercury

Nov 17: Leonids Meteor Shower peak

Nov 24: Venus-Jupiter Conjunction

Nov 28: Jupiter-Venus-Moon conjunction

Nov 29: Saturn-Moon conjunction

Dec 11: Venus-Saturn Conjunction

Dec 13-14: Geminid Meteor Shower peak

Dec 21/22: Winter Solstice

SEPT 26 - OCT 10: ZODIACAL LIGHT

This fall, early risers will have a chance to spot an elusive phenomenon known as "The Zodiacal Light".

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: ESO

In the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada's 2019 Observer's Handbook, Dr. Roy Bishop, Emeritus Professor of Physics from Acadia University, wrote: "The zodiacal light appears as a huge, softly radiant pyramid of white light with its base near the horizon, and its axis centred on the zodiac (or better, the ecliptic). In its brightest parts, it exceeds the luminance of the central Milky Way."

The zodiacal light is caused by sunlight refracting off tiny bits of dust and ice that orbit around the Sun in the plane of the ecliptic (the same plane the planets orbit in). It is thought that this cloud originates from dust and ice blown off of comets.

According to Dr. Bishop, even though this phenomenon can be quite bright, the light is so diffuse that it can easily be spoiled by moonlight, haze or light pollution. Also, since it is best viewed just after twilight, the inexperienced sometimes confused it for twilight, and thus miss out.

On clear nights, and under dark skies, look to the eastern horizon, in the half an hour just before twilight begins to show, from about September 26 through to around October 10. It can also be seen from October 26 through to around November 9.

The best mornings to try to see this phenomenon are likely on either September 27 or 28, and October 27 or 28, since those are the days of the New Moon, and there will be no chance of moonlight spoiling the attempt. Look for a pyramid-shaped white glow, with the base along the horizon and the point angled towards the south.

MOON CONJUNCTIONS WITH JUPITER AND SATURN

Just as we've been seeing all summer long, with the planets Jupiter and Saturn so close together in our night sky, there are three nights every month to pay especially close attention, as the Moon passes right by these two, pairing up with one, then the other, for a very cool show.

On October 3, watch for Jupiter and the Moon, followed by Saturn and the Moon on October 5. Then seen Jupiter and the Moon again on Halloween, Oct 31, and Saturn and the Moon together on Nov 2.

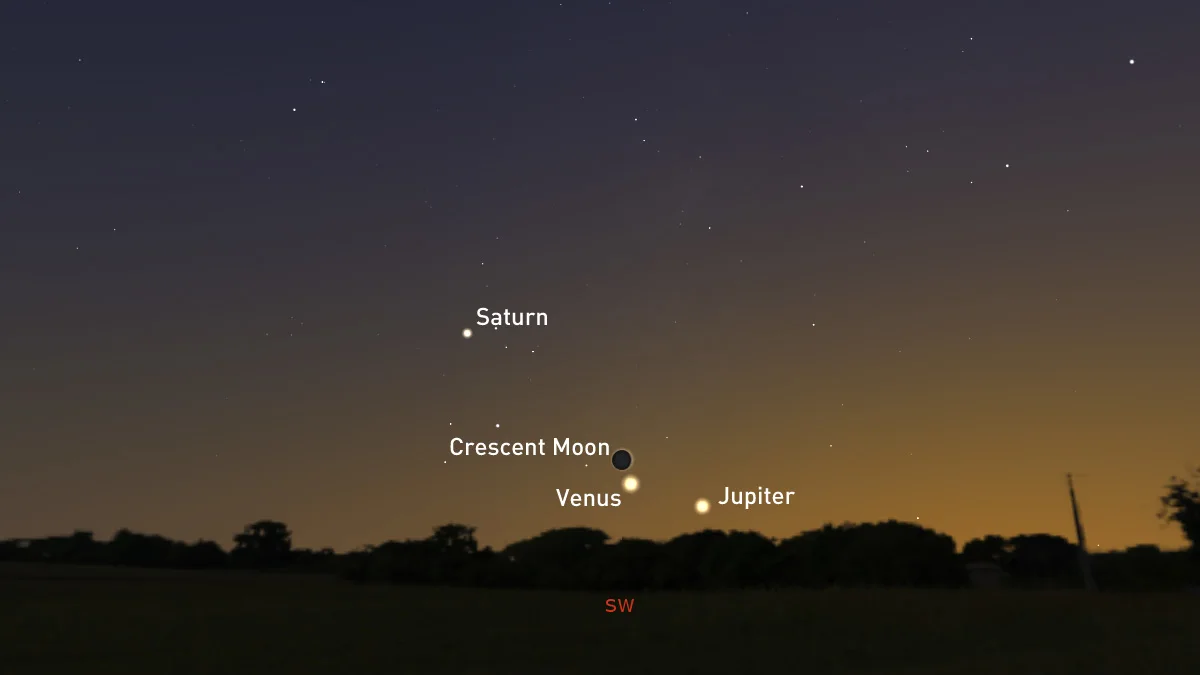

While out trick-or-treating, look towards the western horizon to see Saturn, Jupiter and a thin Crescent Moon. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

This pattern repeats one last time for the season on Nov 28 and Nov 29, with Venus coming in as an added bonus to the Jupiter-Moon conjunction on the 28th.

The view towards the southwest, at around 7:30 p.m. local time on November 28, 2019. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

OCT 8 to NOV 17 - FIVE MINOR METEOR SHOWERS PEAK

Although there are annual meteor showers during all parts of the year, Fall is a particularly active season.

A meteor shower occurs when Earth passes through a stream of fast-moving bits of dust or ice, left behind by the passage of a comet or asteroid. With repeated passes around the Sun, these objects build up persistent trails of meteoroids, and as Earth passes through one of these streams, the atmosphere sweeps up the meteoroids.

When a meteoroid particle enters the atmosphere, the bright streak of light it produces (the meteor) is due to the atmospheric gases in its path being suddenly compressed and heated. The meteor goes out when either the meteoroid slows down enough that it is no longer compressing the air to the point of glowing hot, or the heating vaporizes the meteoroid, leaving nothing behind.

There are four minor meteor showers that peak in the autumn months - the Draconids on October 8, the Southern Taurids on October 10, the Orionids on October 21, the Northern Taurids on November 5 and the Leonids on November 17.

Each of these showers produces maybe 10-20 meteors per hour, on average, but this can vary from year to year. Due to this, they tend not to be very noteworthy events, although dedicated meteor shower watchers who get far away from city lights can still catch these displays.

Some years, these minor meteor showers can experience what's known as an 'outburst', becoming a major shower or even a 'meteor storm', as Earth encounters denser parts of the parent body's meteoroid stream. Meteor scientists have become fairly good at predicting these 'outburts' ahead of time. No outbursts are predicted for 2019, however.

In October, the Draconids will be competing with a fairly bright gibbous Moon, as will the northern Taurids, so neither shower is likely to give a good showing. The Orionids will have a last-quarter Moon to contend with, which will be up for the second half of the night (not good!).

For November, the northern Taurids will take place during a first quarter Moon, which will set around midnight (good timing!), but the Leonids could be largely spoiled by a gibbous Moon that rises early in the evening and remains up the rest of the night.

One thing of note for the Orionids: the meteoroids from this stream hit the top of the atmosphere at exceptionally fast speeds. This makes for brighter meteors, in general, but it can also result in a secondary phenomenon, known as persistent trains.

A persistent train lingers after this fast-moving meteor. Credit: Giphy

A persistent train forms when a meteoroid is travelling so fast through the air that it strips away electrons from the air molecules in its path. These ionized air molecules linger along the meteoroid's path and each one emits a brief burst of light when it pick up a replacement electron to neutralize that ionization.

With so many molecules emitting this light, it shows up to us as a wispy, dimly-glowing ribbon in the sky, as the molecules are carried along by the wind. Since it takes some time for all of the ionized molecules to replace their lost electrons, these trains have been known to persist for up to half an hour!

Scroll down to the bottom of the article for an in-depth guide on how to get the most out of watching meteor showers.

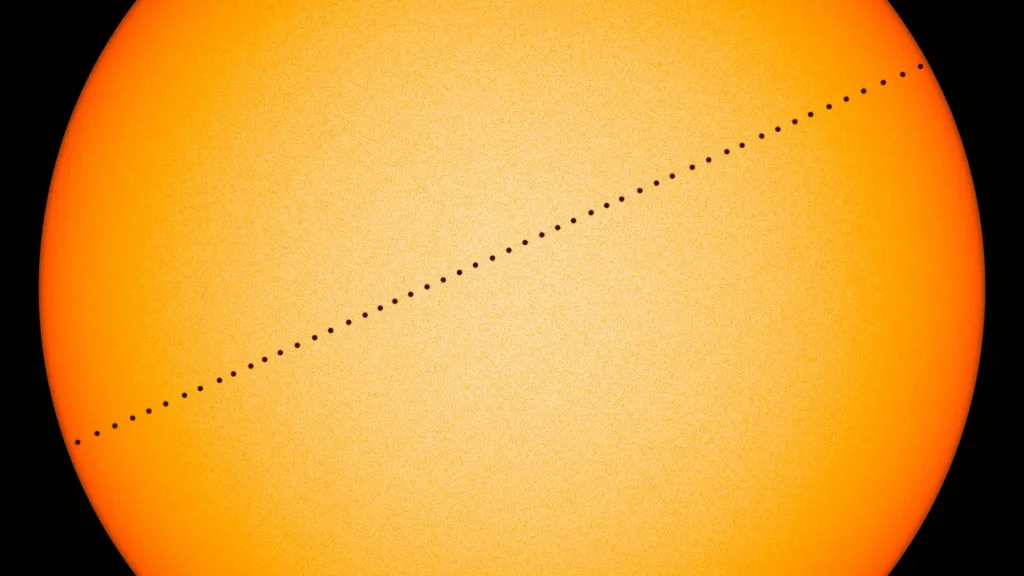

NOV 11: THE TRANSIT OF MERCURY

Among all the events happening in the sky during the next few months, a special show put on by the planet Mercury promises to be the best of them!

On November 11, 2019, Mercury will line up directly between the Sun and Earth to perform what is known as a 'transit'.

This simulated time-lapse view of the transit of Mercury traces the planet's path across the Sun. Credit: NASA/Scott Sutherland

Over the course of roughly five and a half hours, from 7:35 a.m. EST to 1:04 p.m. EST, the tiny planet will show up as a small dark circle crossing the face of the Sun!

This is exactly how astronomers look for alien worlds around other stars!

For more information, check out all the details at our dedicated Mercury Transit viewing guide.

DEC 13-14: GEMINID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

After we get through all the minor meteor shower peaks of this season, we will see what is typically the best meteor shower of the year - the Geminids.

The Geminid Meteor Shower is produced as Earth passes through a stream of dust and gravel left behind by famous "rock comet" 3200 Phaethon.

This tends to be the best meteor shower of the year for three main reasons. 1) It produces the most meteors - averaging 120 per hour under clear skies and with dark sky conditions, 2) the grit and gravel from 3200 Phaethon produce multicoloured meteors when they hit the atmosphere, and 3) with the nights getting longer, there is more time during the night to see this meteor shower in action.

There is one unfortunate thing about this year's Geminids. The timing puts the shower's peak just one night after the Full Moon. That means the light from the Moon will wash out many of the dimmer meteors, even if you are far away from city lights.

This will make observing the event a bit more challenging, but it will still be worth checking out!

How to watch a meteor shower

First, some honest truth: Many people who want to watch a meteor shower end up missing out on the experience, unnecessarily.

I hear this kind of scenario far too often: Someone gets excited to watch the upcoming meteor shower everyone's been talking about. When it gets dark on the night of the event, they step outside into their back yard, directly from the lighted interior of their house, and look up. They don't see anything happening. They wait for about five to ten minutes, still not seeing anything. Then they immediately go back inside, disappointed.

It's not their fault. For most astronomical events, all you need to do is walk outside and look up. Meteor showers require a bit more preparation to watch however, but the rewards for going through the right steps are well worth the effort!

Here is a basic guide on how to get the most out of meteor shower events.

The three 'best practices' for watching meteor showers are:

check the weather,

get away from light pollution, and

be patient.

Having clear skies is very important for meteor-spotting. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin an attempt to see a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on the Out of this World blog, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from light pollution. If you look up into the sky are the only bright lights you see street lights or signs, the Moon, maybe a planet or two, and passing airliners? If so, your sky is just not dark enough for you to see any meteors. It's possible you might catch a bright fireball, but there's no guarantee, and those are typically few and far in-between. So, get out of the city, and the farther away you can get, the better!

Watch below: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village. Once you're out from under the dome of city lights, a multitude of stars becomes visible above your head. In some areas, however, such as in southwestern and central Ontario, and along the St Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high.

Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution, unfortunately, tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over. In these areas, there are dark sky preserves, however, a skywatcher's best bet for dark skies is usually to drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot, after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

Sometimes, based on the timing, the Moon is also a source of light pollution, and its light can 'wash out' all but the brightest meteors. We can't get away from the Moon, so in these situations, we can just make do, as best we can.

Once you've verified you have clear skies, and you've gotten away from sources of light pollution, this is where having patience comes in.

For best viewing, it's crucial to give your eyes time to adapt to the dark. Typically, somewhere between 30-45 minutes of adjustment time is optimal. Just as a warning, if you skip this step, even if you follow the rest of the steps, above, you are going to miss out on a lot of the action.

During this adjustment time, avoid all bright sources of light. That includes overhead lights, car headlights and interior lights, and especially cellphone, tablet and computer screens. Any exposure to bright light during this period will cancel out some or all the progress you've made, forcing you to start over. Shield your eyes from light sources, and if you need to use your cellphone during this time, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off, and reduce the screen's brightness as much as possible. Also, it may be worth finding an app that puts your phone into 'night mode', which will shift the screen colours into the red end of the light spectrum, which has less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly look up into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark. If the Moon is shining brightly in the sky, turn so that you have your back to it.

Now, once you're in a good dark place, under clear skies and your eyes are adapted to the dark, look straight up. The graphics presented for meteor showers often give a 'radiant' point on the field of stars, showing where the meteors appear to originate from, but meteors can flash through the sky anywhere above your head. So, if you focus only on the location of the radiant, you may miss many of the meteors, as they flash through the sky behind you, or beyond the edges of your peripheral vision.

Bring a chair to sit in, or lean back against the side of your car, and tilt your head back, so you can take in as much of the sky at once. Then, just wait for the meteors to show up.