James Webb Space Telescope settles in at 'home', 1.5 million km from Earth

Webb is one step closer to helping us unlock the secrets of the cosmos.

After nearly an entire month of travelling through space, the James Webb Space Telescope has arrived at Lagrange Point 2. Having now made it 'home', Webb is in position for its final stages of deployment before it begins exploring the depths of the universe.

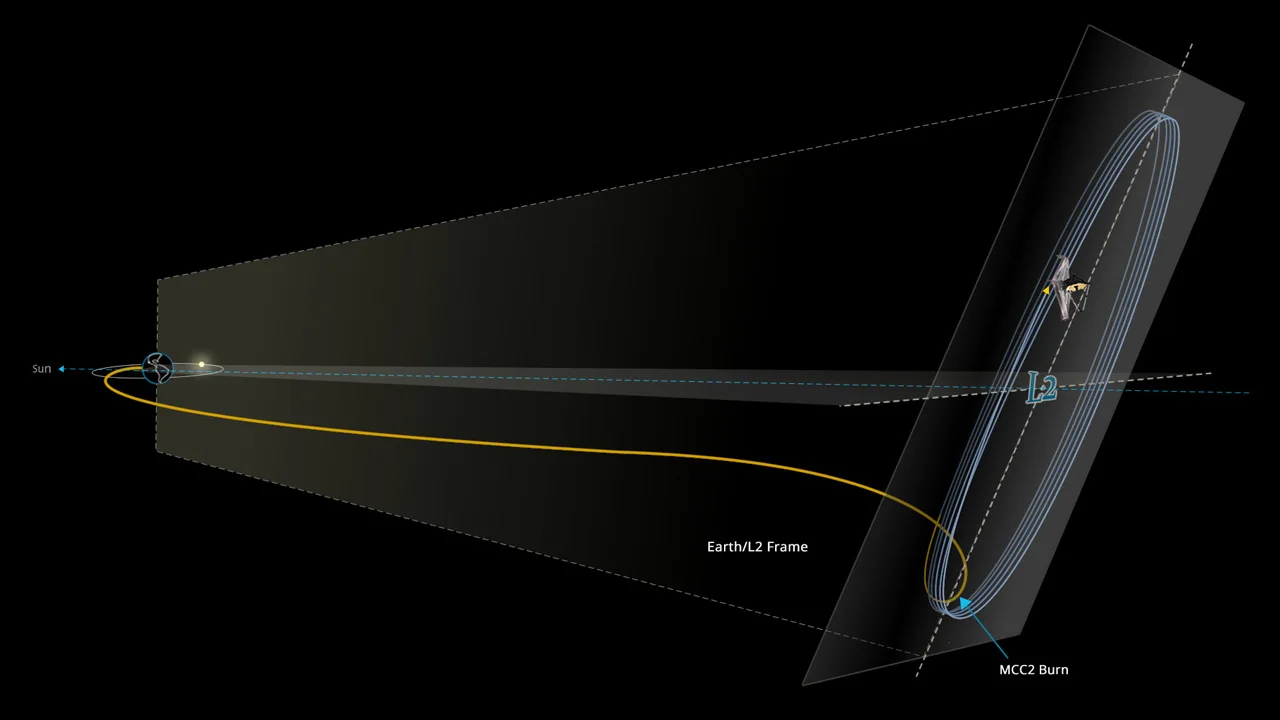

On Monday afternoon, from its position close to 1.5 million kilometres from Earth, the James Webb Space Telescope performed its second and final mid-course correction burn or MCC2. Using its onboard thrusters, Webb spent roughly five minutes pushing itself into just the right position, while picking up just enough speed, to settle into an orbit around Lagrange Point 2. This stable point in space, produced by the gravitational pulls of the Sun and Earth, will now serve as Webb's 'home' for years to come.

This diagram shows Webb's course from Earth orbit to Lagrange Point 2 and its insertion into orbit around L2, from where it will observe the universe. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

"Webb, welcome home!" NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement once the maneuver was complete. "Congratulations to the team for all of their hard work ensuring Webb's safe arrival at L2 today. We're one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can't wait to see Webb's first new views of the universe this summer!"

According to NASA, the planning for this course correction wasn't made until Webb was well underway towards L2. They relied on the rocket to do most of the work of getting the telescope on the right path. However, to arrive at just the right point to slip into its home orbit, they needed to know precisely where Webb was and exactly how fast it was travelling. If they didn't have that information, its final course correction could spell disaster for the mission.

As they explained in a blog post before the maneuver, Webb's orbit around L2 isn't perfectly stable. It's stable enough that, by circling L2, Webb can remain there for decades in near-perfect alignment with Earth and the Sun, without drifting off to one side or the other. However, Webb still has the potential to drift "uphill" in the direction of Earth or "downhill" away from Earth. While one of these is inconvenient and would require correcting, the other would be nearly catastrophic.

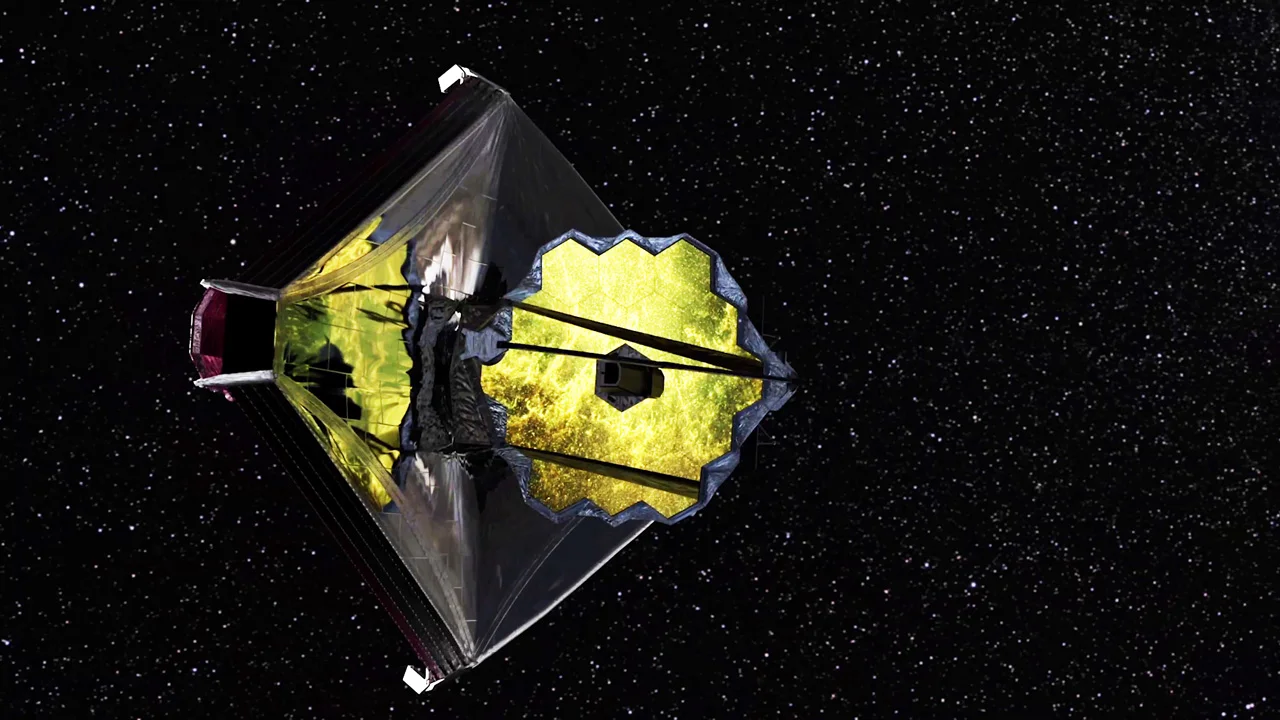

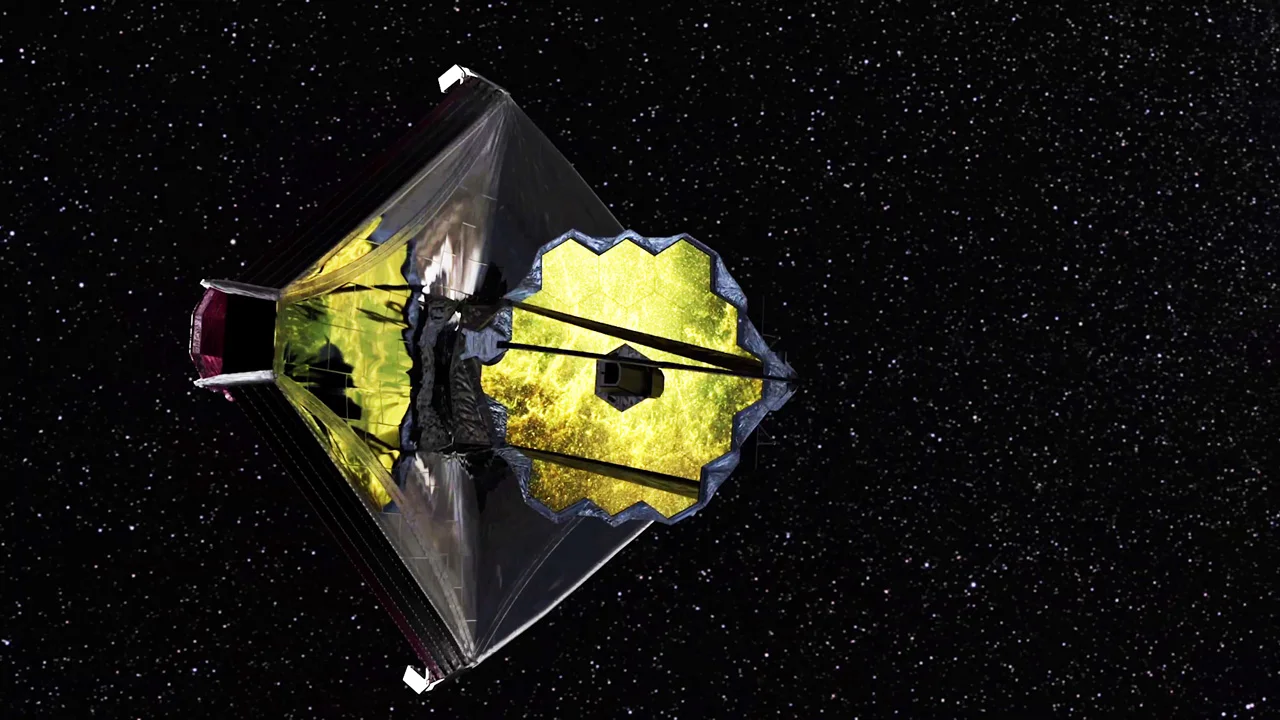

This artist's rendition of the James Webb Space Telescope shows it properly oriented with its mirrors protected by its 70-metre Sun shield. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

"If Webb drifted a little bit toward Earth, it would continue (in the absence of corrective thrust) to drift ever closer; if it drifted a little bit away from Earth, it would continue to drift farther away," wrote Randy Kimble, the Webb Integration, Test, and Commissioning Project Scientist at NASA Goddard. "Webb has thrusters only on the warm, Sun-facing side of the observatory. We would not want the hot thrusters to contaminate the cold side of the observatory with unwanted heat or with rocket exhaust that could condense on the cold optics. This means the thrusters can only push Webb away from the Sun, not back toward the Sun (and Earth). We thus design the launch insertion and the MCCs to always keep us on the uphill side of the gravitational potential, we never want to go over the crest – and drift away downhill on the other side, with no ability to come back."

With Webb's mirrors now fully deployed and the telescope orbiting its home, there will now be a few months of testing and calibration before we see its first "wow" images.

Watch below: Webb scientists detail what's next for the space telescope

According to NASA, Webb's 'first light' images will come during that calibration process. Nearby stars and targets like the Large Magellanic Cloud — a satellite galaxy that orbits the Milky Way — will be used to focus Webb's optics. These first images will be pretty blurry, though.

"When we take what we call the 'first light' of the telescope, we will be expecting to see 18 separate spots, that are probably going to be pretty blurry because everything is going to be misaligned," Lee Feinberg, the Webb Optical Telescope Element Manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said during a press conference. "It's essentially like we're going to have 18 separate telescopes, and the first thing we're going to have to do is align those individual telescopes — the individual primary mirror segments — and then we're going to take those 18 separate spots and put them on top of one another."

Feinberg said that by 'stacking' the images on top of one another, they can then use computer algorithms to determine how far out of alignment each segment is. Then it's just a matter of adjusting the segments accordingly to bring the telescope into full alignment.

"At roughly four months into the mission, at around day 120, is when we think the entire telescope will be aligned," Feinberg said.

"I like to think of it as it's like we have 18 mirrors that are right now, little prima donnas, all doing their own thing, singing their own tune in whatever key they're in, and we have to make them work like a chorus," said Jane Rigby, the Project Scientist for Operations for the James Webb Space Telescope at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. "That is a methodical, laborious process."

"We want to make sure that the first images that the world sees, that humanity sees, do justice to this 10 billion dollar telescope," Rigby explained. "So, we are planning a series of 'wow' images to be released at the end of commissioning, when we start normal science operations, that are designed to showcase what this telescope can do, to showcase all four science instruments, and to really knock everybody's socks off."

The top two panels of this image are taken from the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, showing one section of the field and a close-up on one specific galaxy in that section. The bottom two panels are simulations of what JWST would see in the same area of space. Credit: Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) via Canadian Space Agency

With files from The Weather Network