Fomalhaut's hidden debris rings revealed in amazing detail by JWST

Astronomers wanted to see this alien star's asteroid belt, but JWST revealed so much more!

New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope have revealed previously unseen details of the debris surrounding a nearby young star.

One of the brightest stars in our night sky, Fomalhaut, has attracted plenty of attention from astronomers over the past few decades. Located around 25 light years away, it's relatively close by, making it easy to image with telescopes. Most notably, though, the star is only a little over four hundred million years old and has a wide ring of debris around it. So, it appears to be in the beginning stages of developing one or more planets. As a result, it has been a prime target for observation with our best new telescopes, with the hope being that we may see those planets forming and perhaps gain new insights into how our own solar system formed.

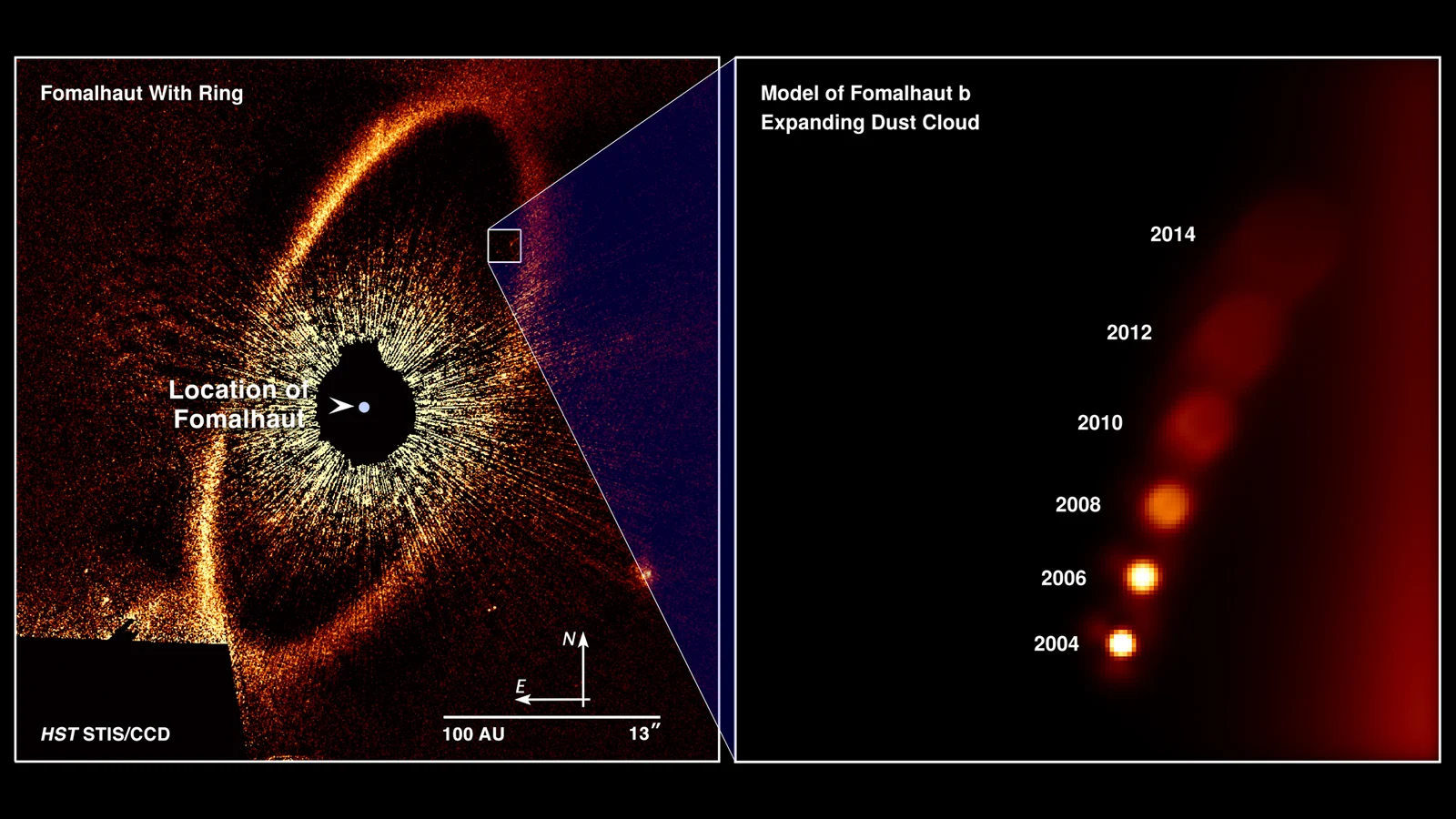

This view of the Fomalhaut system, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2008, reveals the vast ring of debris around the system's edge. At roughly 150 astronomical units (AU) from the star, this ring is thought to be similar to our own solar system's Kuiper Belt, located just beyond Neptune. The star, about twice the size and mass of our Sun, is blocked from view by the instrument, allowing it to image the dimmer material surrounding it. The star's location is indicated by the yellow dot. Credit: NASA, ESA and P. Kalas (University of California, Berkeley)

Indeed, back in 2008, it was announced that the Hubble Space Telescope had spotted a large baby planet orbiting around Fomalhaut inside its debris ring. However, as of 2020, further observations of so-called Fomalhaut-b revealed that it actually wasn't a planet. Instead, it was most likely an immense cloud of dust produced by the collision of two large icy bodies.

Even though Fomalhaut-b turned out not to be real, the young star's debris ring remained an object of interest for those studying planetary system formation.

In late 2022, astronomers pointed the James Webb Space Telescope at Fomalhaut. The goal was to capture the first image of an asteroid belt surrounding another star. They succeeded, but Webb also far exceeded what they intended, revealing that there's more going on around Fomalhaut than anyone knew.

In addition to the outer ring of debris imaged by other telescopes, JWST spotted previously undiscovered structure to the debris closer to the star.

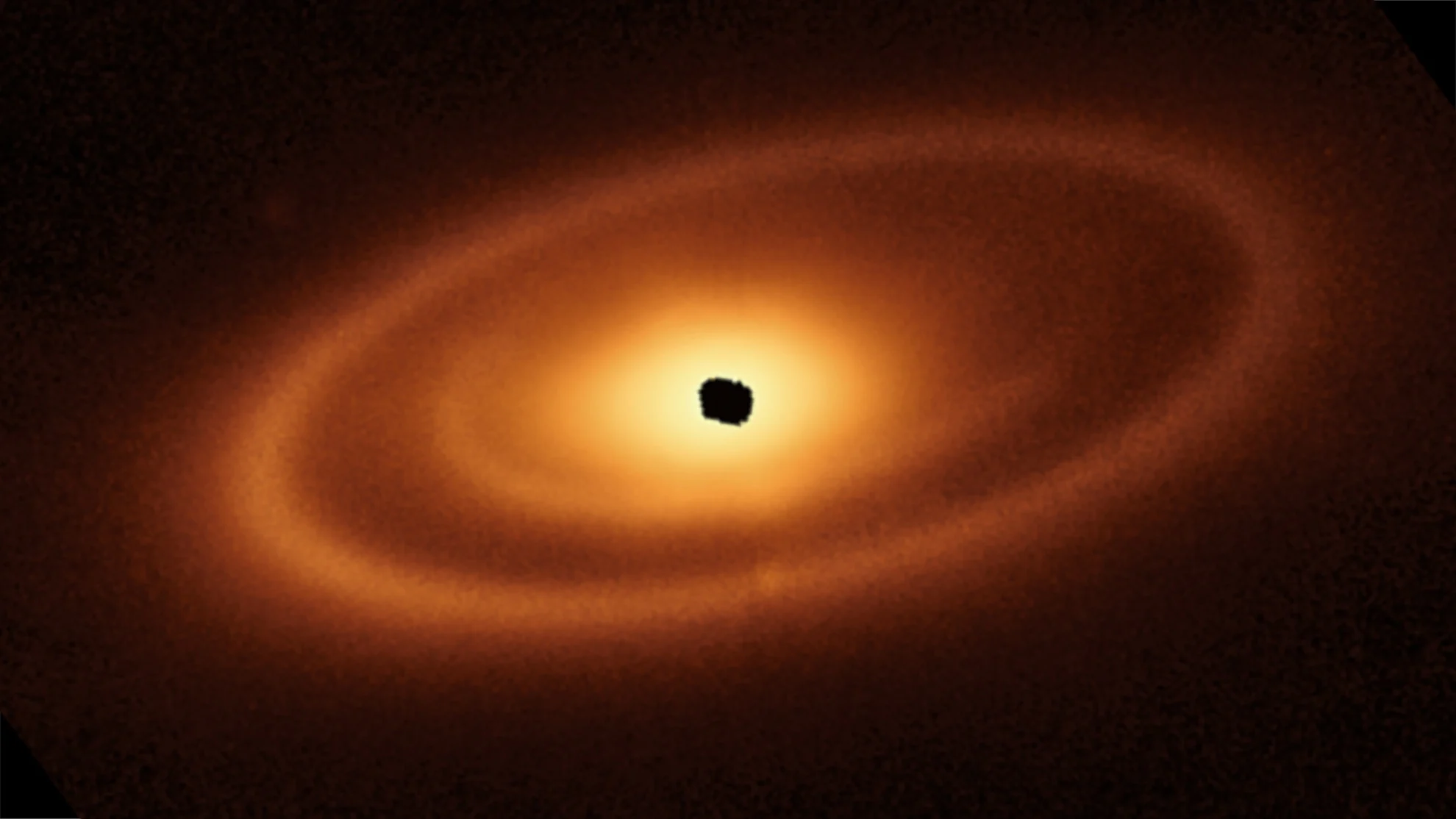

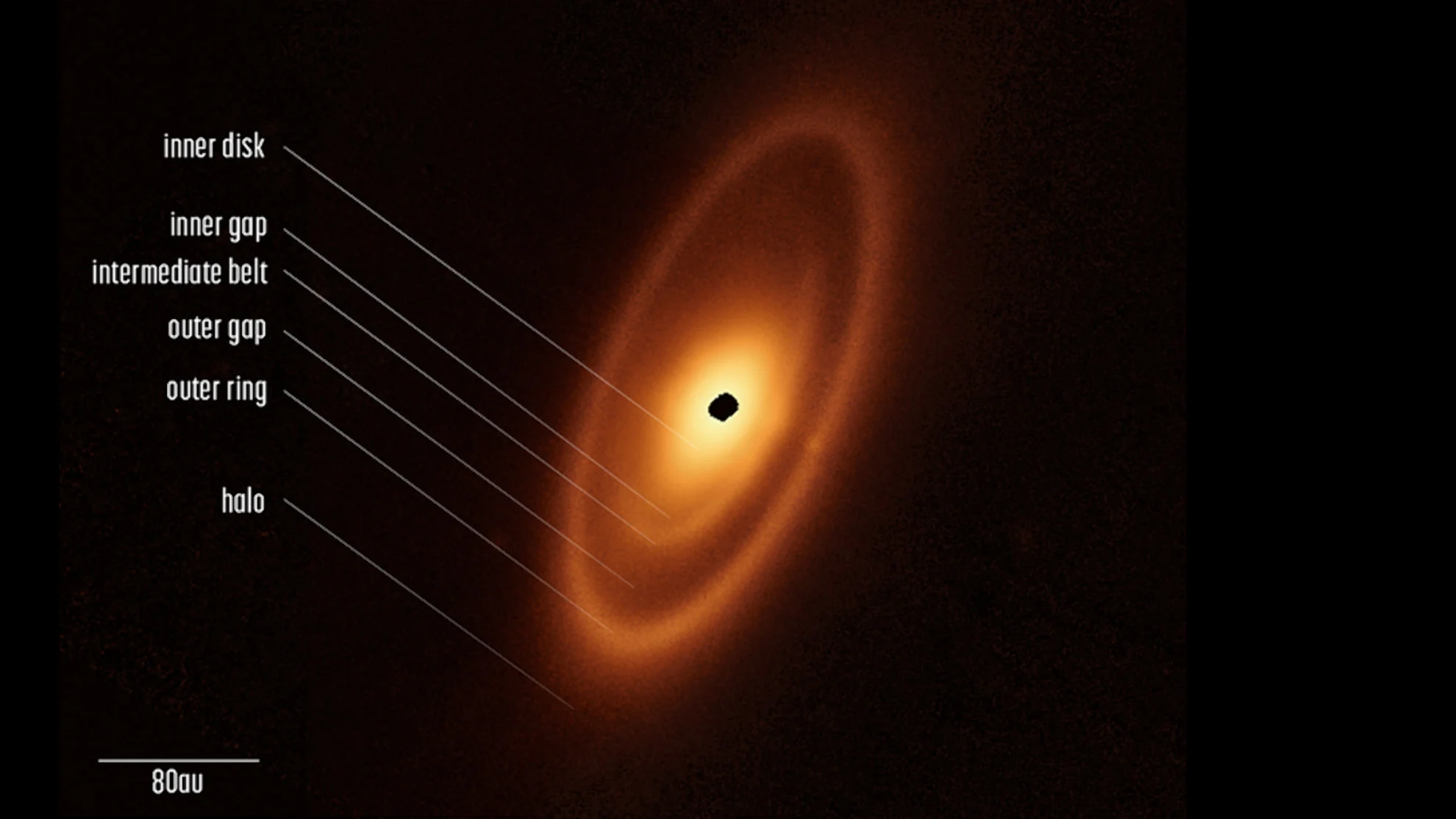

This image from the James Webb Space Telescope's MIRI instrument captures the same outer ring as previous observations but also reveals two other rings of debris closer to Fomalhaut. For a sense of scale, each pixel of the image is over 50 million kilometres wide and our entire solar system out to Pluto would fit into a space roughly half the size of the intermediate ring. As in the previous image, the direct light from the star is blocked from entering the instrument to better reveal the details around it. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Gáspár (University of Arizona). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

The telescope's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) captured an 'intermediate' disk of debris at about 100 AU from Fomalhaut, or a little over twice the distance between Pluto and the Sun. Also, at around 11 AU or the equivalent of just beyond the orbit of Saturn, is an inner debris disk.

According to NASA, while several telescopes before this had seen the outer ring, Webb is the first to spot any of this structure closer to the star. The results of Webb's observations were published in the journal Nature on Monday.

"Where Webb really excels is that we're able to physically resolve the thermal glow from dust in those inner regions," study co-author Schuyler Wolff, from the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, told NASA. "So you can see inner belts that we could never see before."

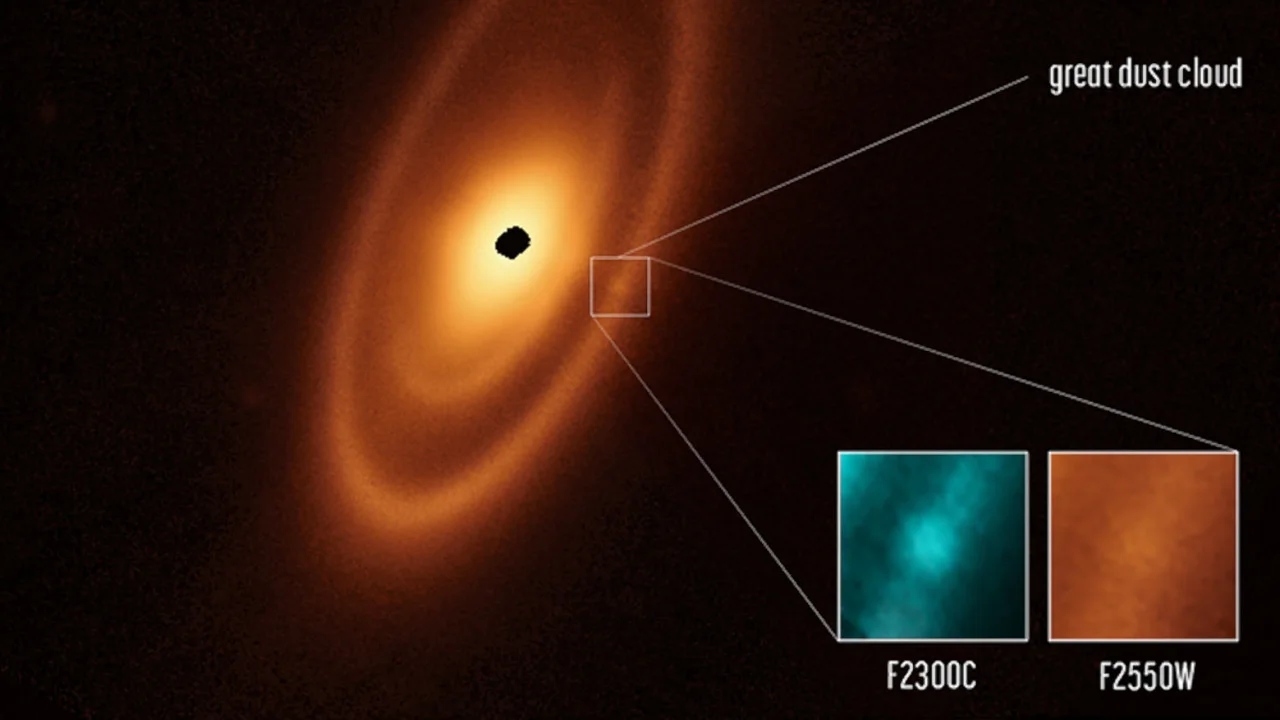

Additionally, the team spotted another structure embedded within the outer ring — a round cloud which they call 'The Great Dust Cloud.'

This image focuses on the Great Dust Cloud in Fomalhaut's outer ring. The inset images show the feature in different wavelengths of infrared light picked up by JWST's instrument. Credit:NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Gáspár (University of Arizona). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

According to the study, they believe this is similar to the cloud of dust that was initially thought to be Fomalhaut-b. However, the team wrote that the Great Dust Cloud appears to contain roughly 10 times more material (dust and ice).

Thus, it may represent the collision of two large icy objects, each nearly the size of the dwarf planet Ceres, crashing into one another at around 1,300 kilometres per hour!

"I would describe Fomalhaut as the archetype of debris disks found elsewhere in our galaxy, because it has components similar to those we have in our own planetary system," András Gáspár, the Steward Observatory astronomer and researcher who led the study, said in an STScI press release. "By looking at the patterns in these rings, we can actually start to make a little sketch of what a planetary system ought to look like — If we could actually take a deep enough picture to see the suspected planets."

Where are the planets?

Just as interesting as the rings of debris are the gaps between them.

"That structure is very exciting because any time an astronomer sees a gap and rings in a disk, they say, 'There could be an embedded planet shaping the rings!'" Wolff explained.

We see this same thing here in our own solar system, with Jupiter's gravity keeping the asteroid belt in place and Neptune shaping the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt. Also, NASA's Cassini orbiter showed us examples from Saturn, as tiny moons like Pan, Daphnis, Atlas, Pandora, and Epimetheus carve gaps in the planet's rings.

"The belts around Fomalhaut are kind of a mystery novel: Where are the planets?" said George Rieke, the Steward Observatory astronomer who leads the MIRI science team.

It's likely that Webb's MIRI image isn't picking up any direct sign of planets simply due to the scale of the image and the brightness of the debris.

These images show the expansion and disappearance of the dust cloud once thought to be exoplanet Fomalhaut-b. When it was still considered a planet, it would have been much smaller than the bright dot spotted in 2004 and 2006. Astronomers attributed its visibility to an immense swarm of dust, ice, and planetesimals that would have surrounded it. Credit: NASA/ESA/A. Gáspár and G. Rieke

Even with their ability to carve these rings out of the star's debris disk, any planets in the system would be small enough at the scale of this image to become lost in the glare. Despite that, they still reveal their presence by the structure of the rings and gaps.

"I think it's not a very big leap to say there's probably a really interesting planetary system around the star," Rieke added.