Winter 2023-2024 could be best in years for observing the night sky

Bright planets, meteor showers, and potential displays of the Northern Lights! This winter could be one of the best in years for watching the night sky!

With longer nights, winter is an excellent time for stargazing, planet viewing, and meteor watching.

Here's what to look for in the night sky for Winter 2023-2024.

Winter Astronomy at a glance

Dec 21-22: Winter Solstice (Northern Hemisphere)

Dec 21-22: Jupiter near the Waxing Gibbous Moon

Dec 22-23 - Ursid meteor shower peak

Dec 26-27: Cold Moon

Jan 2: Earth at Perihelion (closest to the Sun for 2024)

Jan 3-4: Peak of the Quadrantids (best winter meteor shower)

Jan 11: New Moon

Jan 13-14: Saturn near Waxing Crescent Moon (evening sky)

Jan 18-19: Jupiter near the First Quarter Moon

Jan 25-26: Wolf Moon

Feb 4-5: Waning Crescent Moon near bright star Antares

Feb 7-8: Venus near the Waning Crescent Moon (predawn sky)

Feb 8-9: Mercury near the Waning Crescent Moon (predawn sky)

Feb 9: New Moon

Feb 10-11: Saturn near the Waxing Crescent Moon (evening sky)

Feb 14-15: Jupiter near the Waxing Crescent Moon (evening sky)

Feb 22: Venus and Mars close together (predawn sky)

Feb 23-24: Snow Moon (smallest Full Moon of 2024)

Feb 26-Mar 11: Zodiacal Light in western sky after evening twilight

Feb 29: Leap Day

Mar 3: Waning Gibbous Moon near bright star Antares (predawn sky)

Mar 8: Venus near the Waning Crescent Moon (predawn sky)

Mar 10: New Moon

Mar 19/20: Spring Equinox (Northern Hemisphere)

Visit our Complete Guide to Winter 2024 for an in-depth look at the Winter Forecast, tips to plan for it, and much more!

Solstice

On December 21 or 22, depending on where you are across Canada, the Sun will reach its southernmost point in the skies of Earth.

The exact timing of winter solstice is:

at 1:07 a.m. NST, December 22,

at 12:37 a.m. AST, December 22,

at 11:37 p.m. EST, December 21,

at 10:37 p.m. CST, December 21,

at 9:37 p.m. MST, December 21, and

at 8:37 p.m. PST, December 21.

Here in the northern hemisphere, this means the Sun will be at its lowest point in our sky, marking the first day of astronomical winter.

As a result, the 22nd will be the shortest day of the year and, thus, the longest night.

How much daylight and nighttime you see depends on how far north you live.

Kingsville, Ont (the southernmost community in Canada) will see 9 hours, 06 minutes and 18 seconds of sunlight on December 22. Meanwhile, Iqaluit, NU, will have less than half that, with only 4 hours, 20 minutes and 28 seconds of daylight. Farther north, the Sun will have already set for the last time this year and will only rise again in early 2024.

DON'T MISS: Solar max is approaching. Here’s where and how to see the Northern Lights

The Moon

There are three Full Moons in Winter 2023-2024 — December's Cold Moon, January's Wolf Moon, and February's Snow Moon.

The 3 Full Moons of Winter 2024, including their popular names. February's Snow Moon is the smallest Full Moon of the year (the apogee micromoon). Credit: Scott Sutherland/NASA GSFC, with data from Fred Espenak.

We've often heard of supermoons. These bigger and brighter Full Moons occur when the Moon is near the closest approach to Earth (perigee) in its elliptical orbit. The closest of these is known as the Perigee Supermoon. A micromoon is the opposite. It's a Full Moon that occurs when the Moon is close to apogee, its farthest distance from Earth. The most distant of these is called the Apogee Micromoon.

The Cold Moon and Wolf Moon will be relatively 'normal' Full Moons, with respect to their distance and apparent size. However, the Moon will be 405,931 km away from Earth during February's Snow Moon. That's only 372 km from its maximum distance for the month, which makes it a micromoon. Not only that, but this is the farthest and smallest Full Moon for all of 2024.

WINTER 2024: El Niño will play a critical role in the weeks ahead

The Planets

The brightest planets in the night sky will be visible during the season.

Jupiter and Saturn will continue their treks across the sky from the Fall. However, Saturn will be getting closer and closer to the western horizon each night, as Earth swings around the Sun from the ringed planet's position in the solar system. Watch for Jupiter on the night of the winter solstice as it hangs near the Waxing Gibbous Moon, then find it near the First Quarter Moon on January 18-19 and the Waxing Crescent Moon on the night of February 14-15.

Jupiter and the Waxing Crescent Moon in the western sky on the evening of February 14. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

We can see Saturn in the evening sky, close to the Waxing Crescent Moon on January 13-14, and again on February 10-11. After that, the planet is lost in daylight for the rest of the season.

Venus will be visible in the predawn sky, but will rise earlier and earlier as the season progresses and it gets closer to the Sun from our point of view. Watch for it each morning, but especially on February 8, then February 22, when it will be very near the planet Mars, and again on March 8, when it will be near the Waning Crescent Moon again.

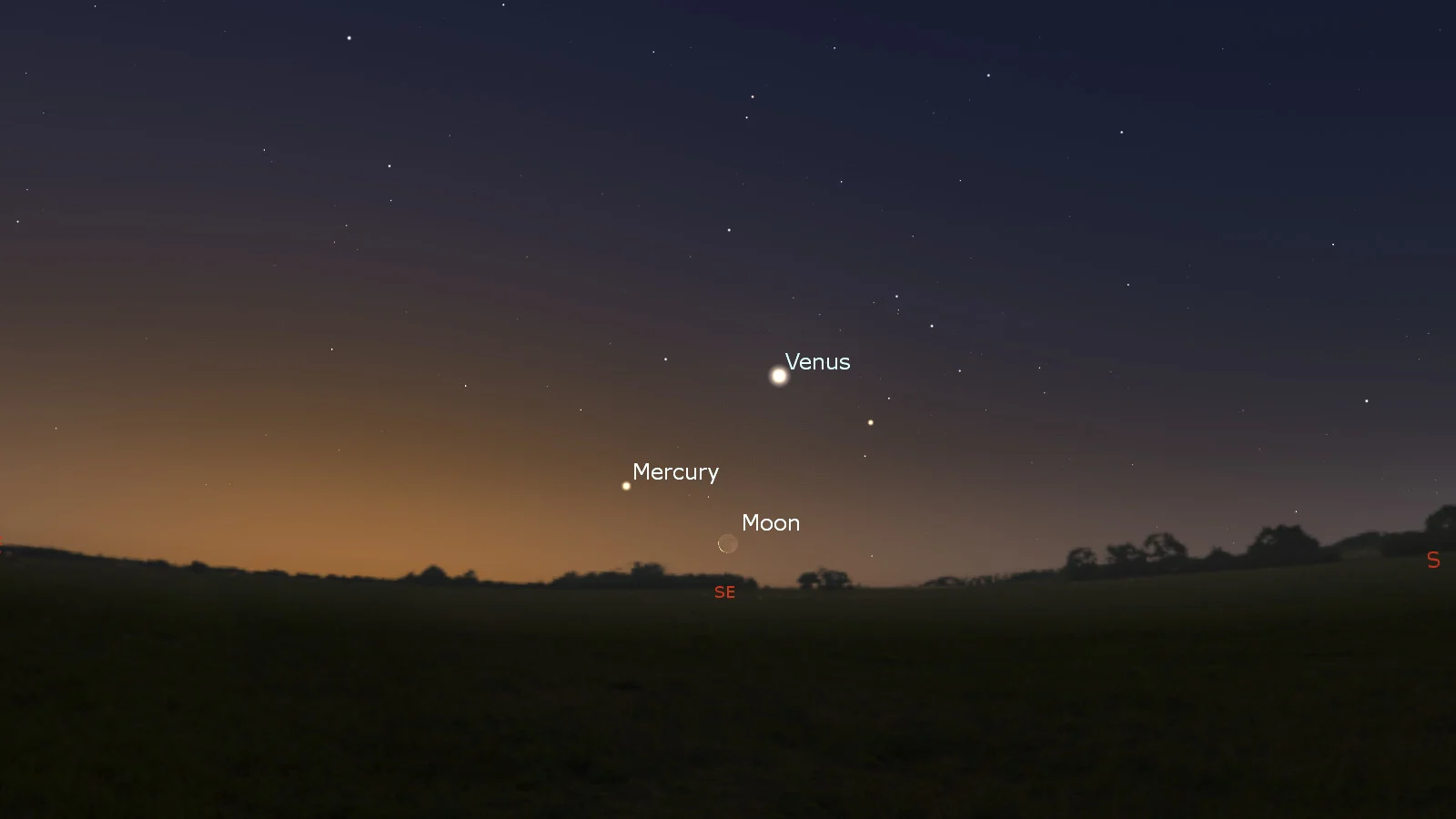

Although Mercury was too close to the Sun for us to see it towards the end of autumn, it reappears in the predawn sky in early winter. Watch for it to climb higher in the predawn sky each morning up until January 9, when it reaches its highest. On that same morning, the small planet will form a triangle with Venus and the thin Crescent Moon.

Three celestial bodies form a triangle above the eastern horizon in the predawn sky on January 9, 2024. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Mercury will remain visible in the predawn sky until early February, when it disappears from sight again.

The planet Mars, which has been on the other side of the Sun from Earth for months, finally emerges from the glare of daylight, just before sunrise in early to mid February. It won't be easy to see in morning twilight, though. We'll have to wait until spring to get a better look at it. See it very close to Venus on the morning of February 22.

Meteor Showers

Look up any night and you could spy a random meteor zipping across the sky above. At certain times of the year, though, we can see several meteors streaking by every hour. These are known as meteor showers and we see two of them during the winter months — the Ursids and the Quadrantids.

The Ursids

The Ursid meteor shower is a relatively minor one that is active between mid-to-late December. The night after the solstice, on December 22-23, this shower reaches its peak. Although the Ursids typically only produce around 10 meteors per hour, that number can sometimes jump up to 50 per hour. This may be one of those times, as astronomers have predicted that Earth will encounter a slightly denser part of the Ursids stream on the day of the peak.

The Quadrantids

The best meteor shower of winter and one of the three best showers of the year, the Quadrantids peak on the night of January 3-4.

The radiant of the Quadrantids, in the NE sky, in the hours after midnight on January 3-4, 2023. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The meteor shower 'radiant' for the Quadrantids (the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to radiate) never sets below the horizon. Thus, viewers only need to wait until the sky is dark enough to spot meteors.

Occurring on the same night as the last quarter Moon, the timing could be a bit better. Be sure to plan your viewing either for the hours between sunset and midnight, or just keep your eyes to the north so that, after the Moon rises around midnight, it stays out of your direct field of view.

The exact number of meteors from the Quadrantids can vary from year to year. Typically, it produces around 120 per hour, which amounts to about two every minute. However, the Quadrantid peak is a bit shorter than those we see from other meteor showers (only about 6 hours long). Thus, we need to be able to watch in that narrow range to get the most out of it. This year, the peak should be centred around midnight, EST, on the 3rd to 4th, which is excellent timing for observers in North America.

While most meteor showers are produced by comets, Quadrantid meteors originate from 2003 EH1, an asteroid that could be an 'extinct comet' — one that has lost all of its ice after repeated trips around the Sun. This puts the Quadrantids in an exclusive club along with the Geminids, which come from 'rock comet' 3200 Phaethon, and the Northern Taurids, which originate from asteroid 2004 TG10 (which may, itself, be a piece of a shattered comet)!

READ MORE: How to get the most out of meteor showers and other night sky events

Earth at perihelion

This event isn't so much something to see as it is something to experience.

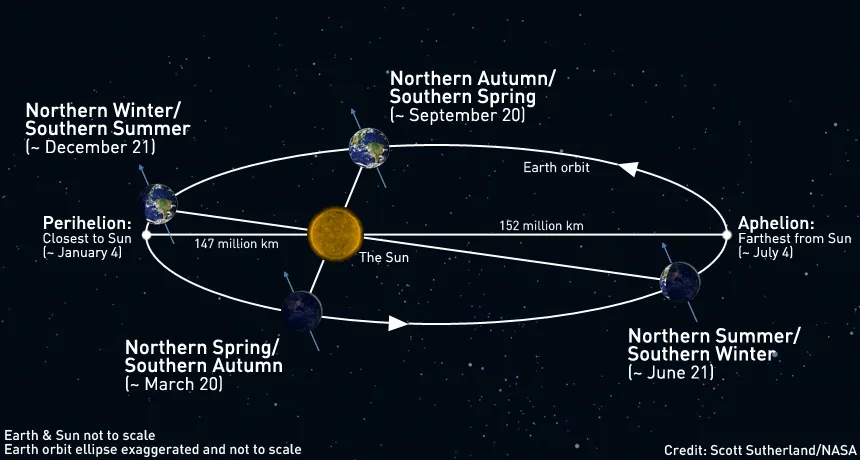

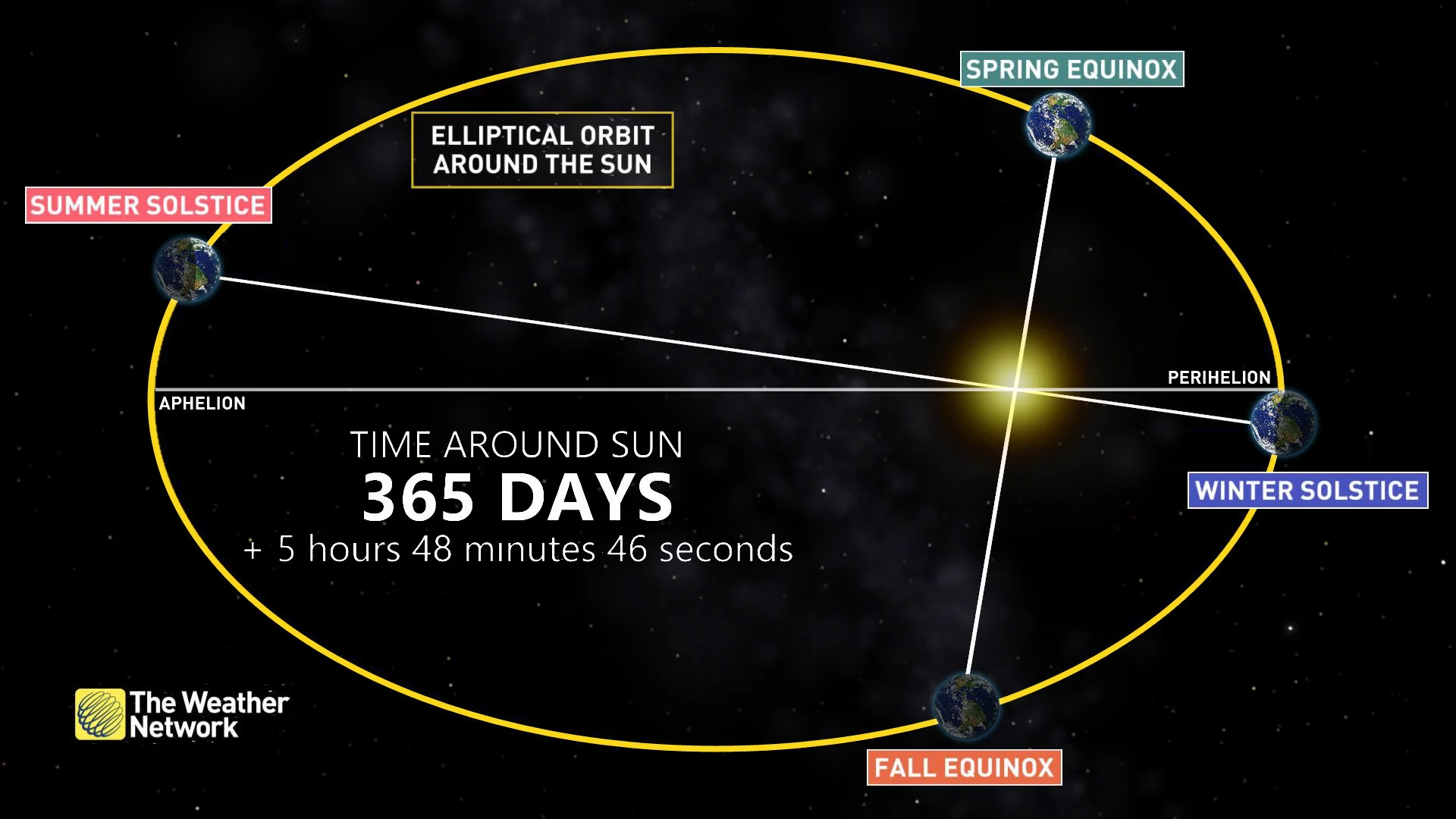

Each year in early January, Earth reaches a point in its elliptical orbit known as perihelion — the planet's closest distance to the Sun for the entire year.

Earth's orbit around the Sun, noting the Solstices, Equinoxes and the timing of perihelion and aphelion. The image is not to scale, and the ellipse of Earth's orbit has been exaggerated. Credit: NASA/Scott Sutherland

If you want to mark the event, even if it's just to pause for a short break, it occurs at exactly 00:39 GMT on January 3, 2024. For those of us in Canada, that translates to:

9:09 p.m. January 2 NST

8:39 p.m. January 2 AST

9:39 p.m. January 2 EST

7:39 p.m. January 2 CST

6:39 p.m. January 2 MST

5:39 p.m. January 2 PST

According to retired NASA scientist Fred Espenak, at that exact moment, Earth will be roughly 147,100,633 kilometres away from the Sun.

Will you feel anything when this occurs? Not specifically from the astronomical event, but it will still be cool to mark the moment when it happens!

The Zodiacal Light

Have you ever been out in the hours just after sunset or before sunrise and noticed a bright pyramid of light covering a significant portion of the sky? If so, you may have seen an elusive phenomenon known as the Zodiacal Light.

For about two weeks starting on February 26, turn your gaze to the western horizon in the half hour or so after evening twilight. Specifically, you are looking for a diffuse white glow in the shape of a pyramid, with its base along the horizon and peak extending high into the sky.

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: European Southern Observatory (ESO)

The zodiacal light is produced by sunlight glinting off grains of dust that float in an immense disk surrounding the Sun. However, we can only see this effect at specific times of the year. In February and March, it appears in the western sky, in the half-hour after evening twilight, in the two weeks just after the Full Moon. In September and October, we can see it in the eastern sky, in the half-hour or so before morning twilight, during the two weeks following the New Moon.

New research has shed fresh light on this phenomenon. It was once thought that the dust cloud that produces the zodiacal light originated from comet tails. However, researchers used data from NASA's Juno spacecraft to reveal it may actually be Martian dust floating in space!

The best way to be sure that you really are seeing this phenomenon is to look up the exact timing of twilight in your area so that you know precisely when it begins, and get away from city lights so that you are sure light pollution isn't going to spoil the view.

Equinox

At precisely 3:06 GMT on March 20, the Sun will appear to cross Earth's celestial equator, ushering in Spring in the northern hemisphere.

Due to this exact timing, though, different parts of Canada actually experience this on different days:

at 12:36 a.m. NDT, March 20,

at 12:06 a.m. ADT, March 20,

at 11:06 p.m. EDT, March 19,

at 10:06 p.m. CDT, March 19,

at 9:06 p.m. CST/MDT, March 19, and

at 8:06 p.m. PDT, March 19.

Solar Maximum is approaching

One final note to keep in mind during the winter months: The Sun is nearing the peak of its 11-year solar cycle. That means we're going to see more frequent and more powerful solar flares, as well as more aurora activity from the solar wind and solar storms (coronal mass ejections).

With the winter months having longer nights, this will be a prime time to get out to see the Northern Lights shine in the sky. Watch for updates on space weather forecasts throughout the season!

(Thumbnail courtesy Claire Smith, who snapped the amazing view of the winter night sky from the shores of Georgian Bay in early 2017.)