NASA's DART spacecraft is on its way to intentionally crash into an asteroid

If an asteroid were to threaten the safety of life on Earth in the future, this 'kinetic impactor' mission may reveal how to deflect it, thus saving us all.

NASA's DART spacecraft has launched on a mission to test whether we could deflect a dangerous asteroid that was headed straight for Earth.

Late on the night of Tuesday, November 23, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, lifted off from Vandenberg Space Force Base in Hawthorne, California, perched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 booster rocket.

DART lifted off at 1:21 a.m. EST from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

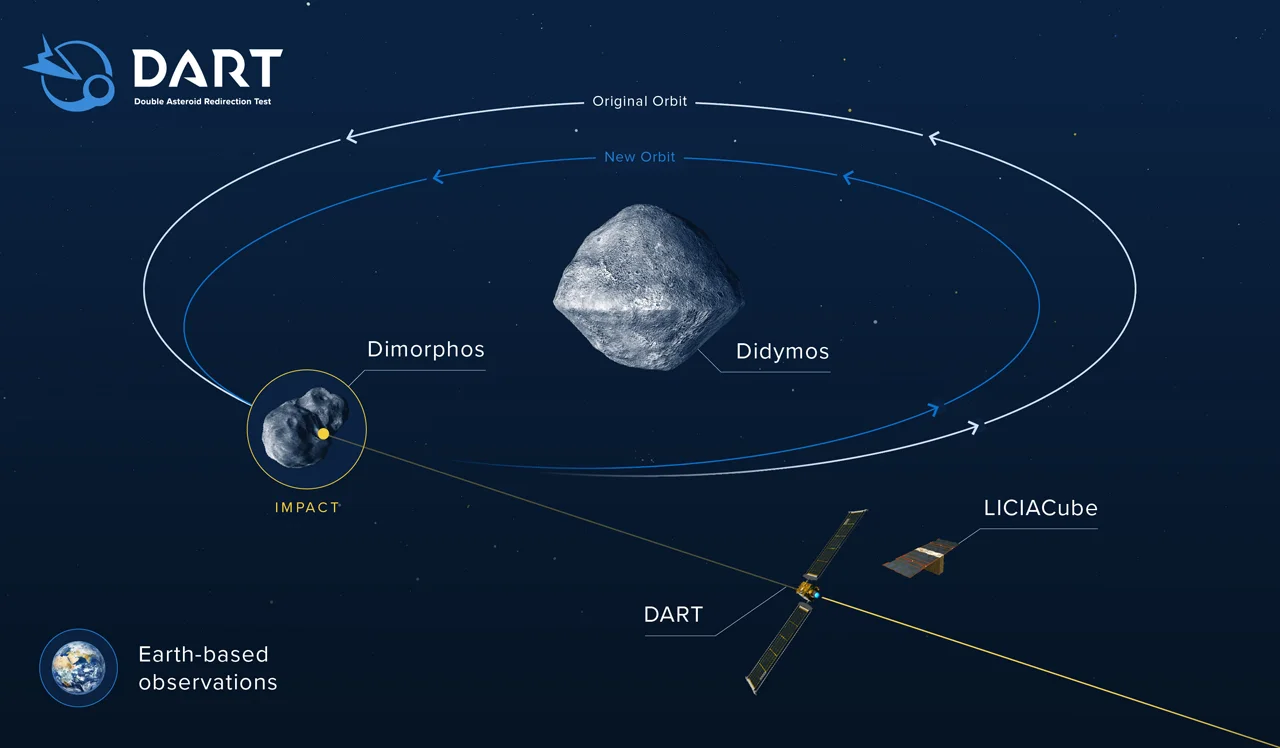

Now underway, the uncrewed, robotic DART spacecraft is speeding towards a fateful rendezvous with a pair of asteroids named Didymos and Dimorphos. When it arrives at its destination in late September of 2022, DART has a singular purpose.

Unlike previous asteroid missions, which were designed to orbit and study the objects, NASA has very different plans for DART, as 'kinetic impactor' test. As it approaches the Didymos system, travelling at around 24,000 kilometres per hour, the spacecraft will use its cameras to autonomously home in on Dimorphos. Once it is locked on target, DART will then intentionally crash itself into the space rock.

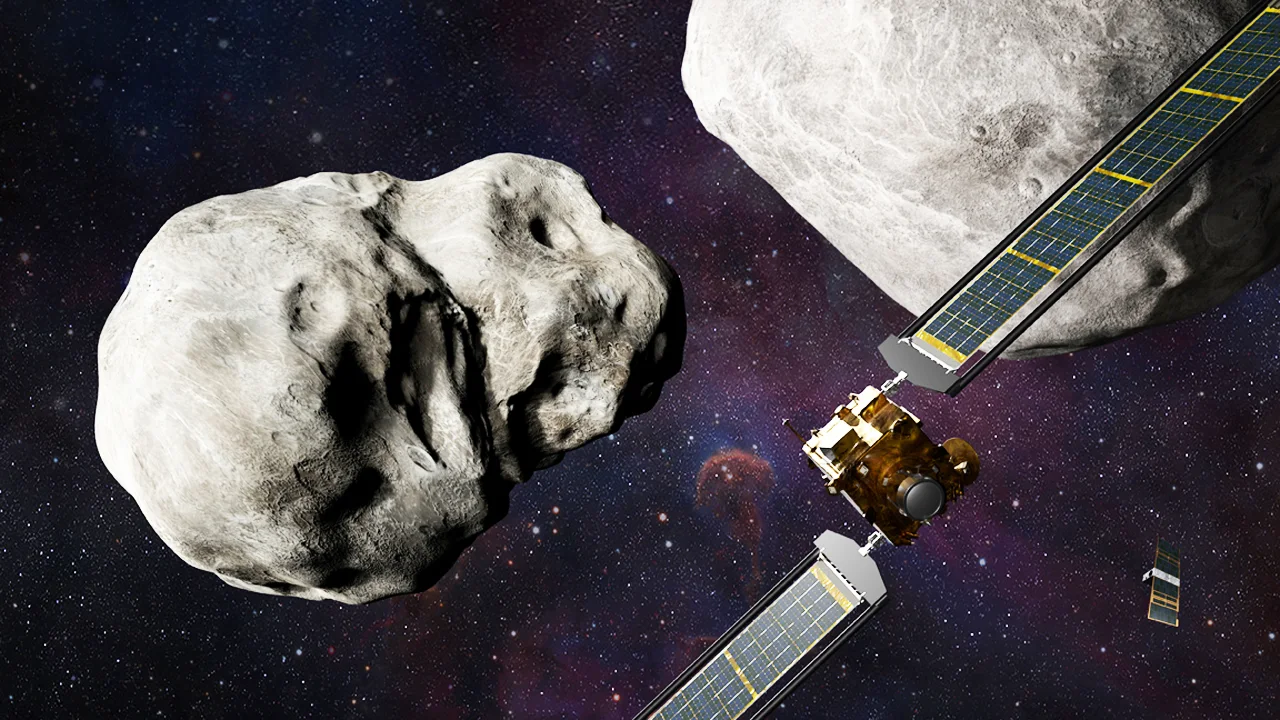

This artist's impression shows DART on final approach along its crash-course towards Dimorphos. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

The ultimate goal is to see if DART's impact can produce even the tiniest change in Dimorphos' orbit.

"DART is turning science fiction into science fact and is a testament to NASA's proactivity and innovation for the benefit of all," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a press release on Wednesday. "In addition to all the ways NASA studies our universe and our home planet, we're also working to protect that home, and this test will help prove out one viable way to protect our planet from a hazardous asteroid should one ever be discovered that is headed toward Earth."

The results of the impact will be recorded, close-up, by a small cubesat named LICIACube (Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids), which was provided by the Italian Space Agency. While it will remain attached to DART for most of the mission, LICIACube will detach and follow along at a safe distance during the impact test, snapping images with its cameras. In addition, since Didymos and Dimorphos will be reasonably close to Earth at the time (around 10 million km away, or 28 lunar distances), telescopes will be carefully watching the orbit of Dimorphos in the aftermath to measure how it changes.

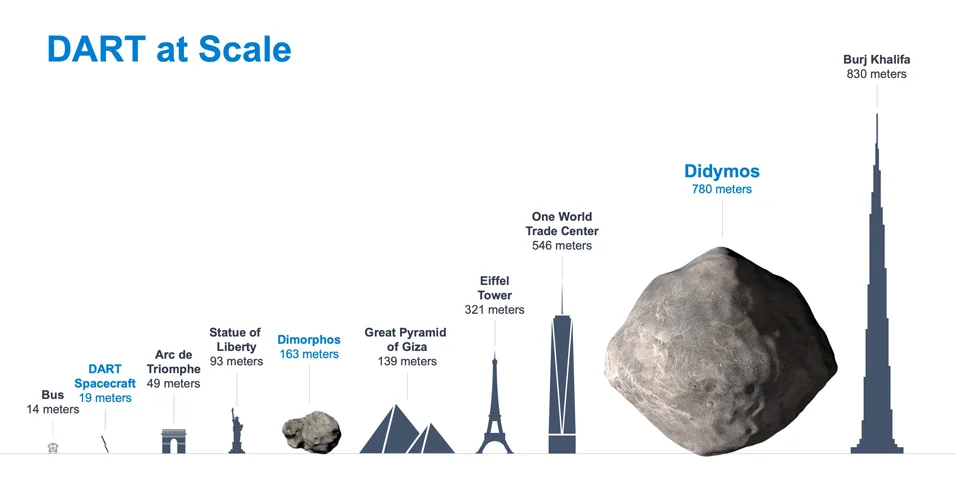

DART is tiny compared to Dimorphos. While the spacecraft (minus its solar panels) is about the size of a vending machine, Dimorphos is roughly the same size as the Great Pyramid of Giza. So, any change brought on by the impact test will be small. It currently takes Dimorphos around 11 hours and 55 minutes to make a complete orbit of Didymos. NASA estimates that the impact should shorten that orbit by several minutes. This will cause Dimorphos to orbit slightly closer to Didymos, as well.

This graphic shows the Didymos system, with binary asteroids Didymos and Dimorphos, and DART's intended trajectory on its crash course towards the smaller of the two space rocks. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins Advanced Physics Lab

Any change in the orbit will be a success for DART's mission, though.

According to the team that designed the spacecraft, at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, the measurements gathered during the impact and its aftermath "will be used to both validate and improve scientific computer models that are critical to predicting the effectiveness of kinetic impact as a reliable method for asteroid deflection."

Thus, in the unlikely case that some asteroid becomes a threat to us in the future, and we spot it with enough lead time before impact, the data we gather from DART could provide us with the means to deflect that asteroid and save ourselves from catastrophe.

"If we know how to deflect space rocks, these low-risk events can be averted. When you shoot a hockey puck, even a slight tip can cause a large deflection by the time it gets to the net," Paul Wiegert, an asteroid expert at Western University's Institute for Earth and Space Exploration, said in a statement. "We need to learn how to do the same thing for asteroids and the DART mission is an important part of this testing and learning process."

THE DIDYMOS SYSTEM

Didymos and Dimorphos are a binary asteroid — two asteroids bound together by gravity, with one orbiting the other.

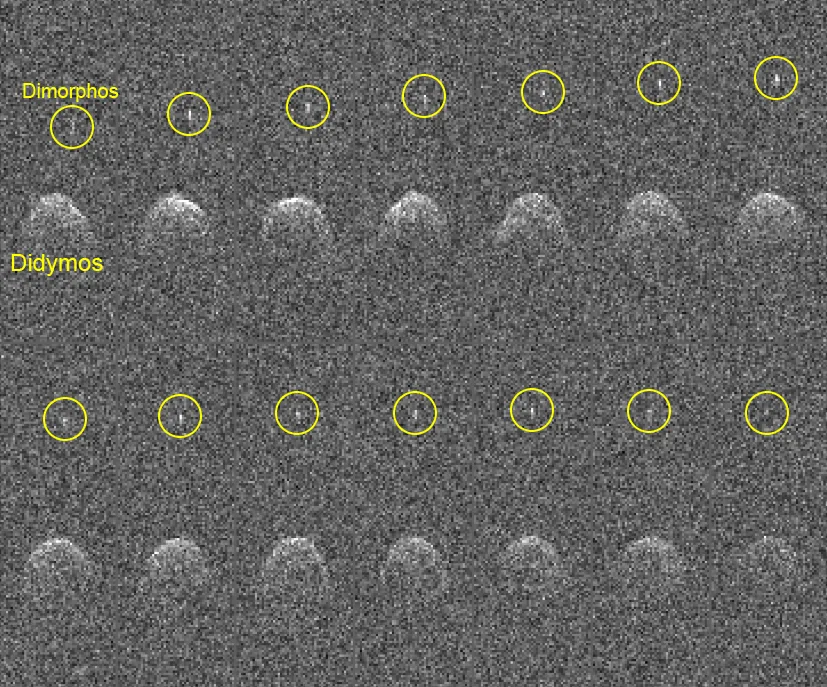

Originally spotted in 1996 and simply named "1996 GT" to start, this pair was thought to be a single, unremarkable asteroid at the time. It wasn't until late 2003, when they made a reasonably close approach to Earth, at a distance of just over 7 million km (or about 18x the distance to the Moon), that astronomers discovered the smaller companion asteroid.

The Didymos system, as imaged by radar from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico during its 2003 flyby of Earth. Credit: Arecibo Observatory/NASA

By bouncing radio waves from the Arecibo Observatory off the pair during its flyby, the primary asteroid was confirmed to be around 800 metres wide. The binary companion was estimated to be about 170 metres wide, and it orbited once every 12 hours or so. The pair were named Didymos, which is Greek for "twin". The smaller of the pair was nicknamed Didymos B or "Didymoon" until it was given the official name of Dimorphos (Greek for "having two forms").

It's important to note that Didymos and Dimorphos are not a threat to Earth — neither now nor at any point in the future. They do not even appear on NASA's Sentry Table of Impact Risk. The orbit of this pair is well known, and the closest it ever comes to Earth is on November 4, 2132, when it will be around 5.8 million kilometres away. That's more than 15 times farther away than the Moon. Also, this impact test will not have any effect on their impact risk for the future.

As a target for a kinetic impactor test, Dimorphos was the perfect option for NASA. The pair pass fairly closely by Earth every 19 years or so (within about 10 million km). Thus, as long as you time it right, you can fly a spacecraft there in a reasonable amount of time. Also, Dimorphos' orbit around Didymos is a lot slower than Didymos' orbit (or the orbit of other asteroids) around the Sun. Therefore, it's easier to deflect than a single asteroid. This same slower orbit also makes it easier for telescopes to detect the changes caused by the impact.

DART, Didymos, and Dimorphos are presented alongside various objects and structures to show their relative sizes. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins Advanced Physics Lab

Finally, this binary pair was a much less risky option than other targets. Science fiction has certainly presented us with many nightmare scenarios that stem from the unintended consequences of science and space missions. However, regardless of the test's outcome, Dimorphos will continue to circle around Didymos, and both will continue on their path around the Sun, with no change to their relative risk to Earth.

"We have not yet found any significant asteroid impact threat to Earth, but we continue to search for that sizable population we know is still to be found," Lindley Johnson, planetary defence officer at NASA Headquarters, said in the NASA press release. "Our goal is to find any possible impact, years to decades in advance, so it can be deflected with a capability like DART that is possible with the technology we currently have."

"DART is one aspect of NASA's work to prepare Earth should we ever be faced with an asteroid hazard," Johnson added. "In tandem with this test, we are preparing the Near-Earth Object Surveyor Mission, a space-based infrared telescope scheduled for launch later this decade and designed to expedite our ability to discover and characterize the potentially hazardous asteroids and comets that come within 30 million miles [48 million km] of Earth's orbit."