New proposal expands 'planet' definition to thousands of alien worlds

A new definition for the astronomical term 'planet' would apply to all alien worlds we've discovered so far, but would still leave Pluto off the list.

A new and improved definition for the term 'planet' will soon be proposed that would expand the title beyond the confines of solar system to include every alien world we discover.

In 2006, over 2,500 scientists and researchers met in Prague for the triennial International Astronomical Union's General Assembly. There, they voted to adopt a new definition for the term 'planet', one that was proposed to help clear up any confusion and end any debates.

What they agreed upon at the time was that a planet was a celestial object that:

orbits the Sun,

is massive enough that its own gravity would cause it to form into a spherical shape (what is known as 'hydrostatic equilibrium'), and

has cleared the area around its orbit of other objects.

This artist's impression shows an idealized view of the solar system, compacting their orbits to fit all of the major objects into the same view and exaggerating their sizes to make them easier to see. (NASA/JPL)

When the dust settled from this decision, we had a new total of eight planets in our solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Pluto, which had been grouped among these other objects as a planet since its discovery in 1930, didn't make the cut. It was moved into the classification of 'dwarf planet', along with Ceres, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake.

New definition needed

We're long overdue for a fresh take on the definition of what is and what isn't a planet, though.

In August, the IAU will hear a new proposal written by Dr. Jean-Luc Margot from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Dr. Brett Gladman, a professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC), and Tony Yang, a student at Chaparral High School, in Temecula, California.

"The Earth isn't completely round, so how round does a planet have to be?" Dr. Gladman said in a UBC press release. "If you look at a world orbiting another star with current technology, we can't measure the shape."

"Additionally, Jupiter's orbit is crossed by comets and asteroids, as is Earth's. Have those planets not cleared their orbit and thus, aren't actually planets?" Gladman added. "We're drawing a line in the sand by putting some numbers to these definitions, to encourage our community to start the discussion: What exactly is a planet?"

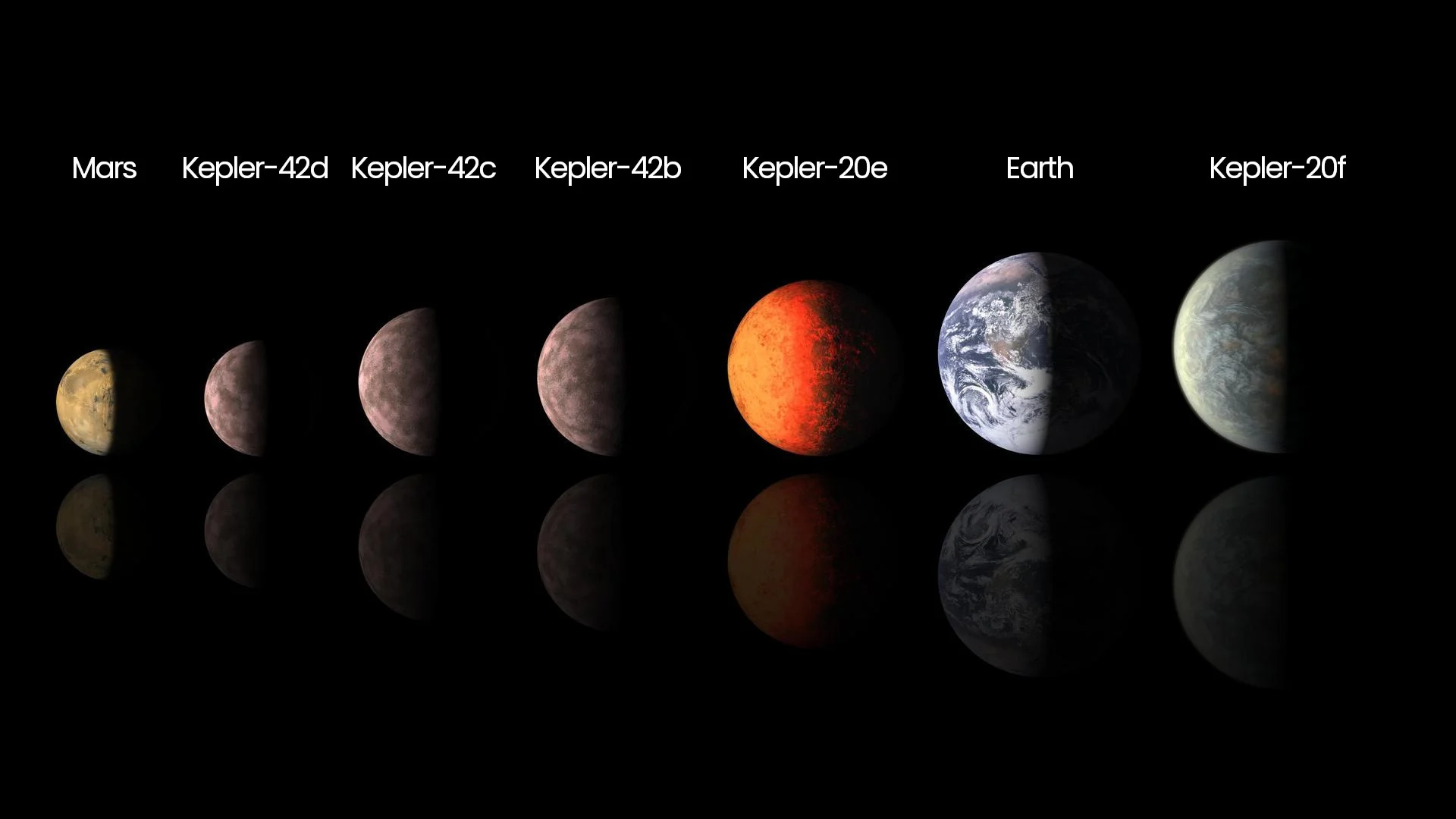

The five smallest exoplanets found by the Kepler Space Telescope as of 2012 are shown here with Mars and Earth added for comparison. Of these seven worlds, only Mars and Earth can currently be classified as planets. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

There are problems with the current definition even in our own solar system. However, they get even worse when we look beyond.

"We now know of thousands of 'planets' orbiting other stars, but the IAU definition applies only to those in our solar system, which is obviously a big flaw," explained Dr. Margot, who is the lead author of the paper describing this proposal. "We propose a new definition that can be applied to celestial bodies that orbit any star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf."

New proposal

In their paper, the definition reduces down to just two main points. A planet is a celestial object that:

orbits one or more stars, stellar remnants (white dwarf, neutron star, etc.), or brown dwarfs, and

has a mass that's at least one-third of the mass of Mercury (10^23 kg) but no greater than 13 times the mass of Jupiter (2.5x10^28 kg).

The second clause establishes some hard limits on what is a planet, based on the object's mass.

"Having definitions anchored to the most easily measurable quantity — mass — removes arguments about whether or not a specific object meets the criterion," Dr. Gladman explained. "This is a weakness of the current definition."

The lower limit — roughly one-third of the mass of Mercury — handles two of the criteria set by the current definition. It ensures that the object is massive enough to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium, and it would be massive enough to be 'dynamically dominant' over its orbit. That means it will have already swept up or expelled other similarly-sized objects from its orbit, and its mass will be far greater than the total mass of all other objects that may remain in its orbital zone.

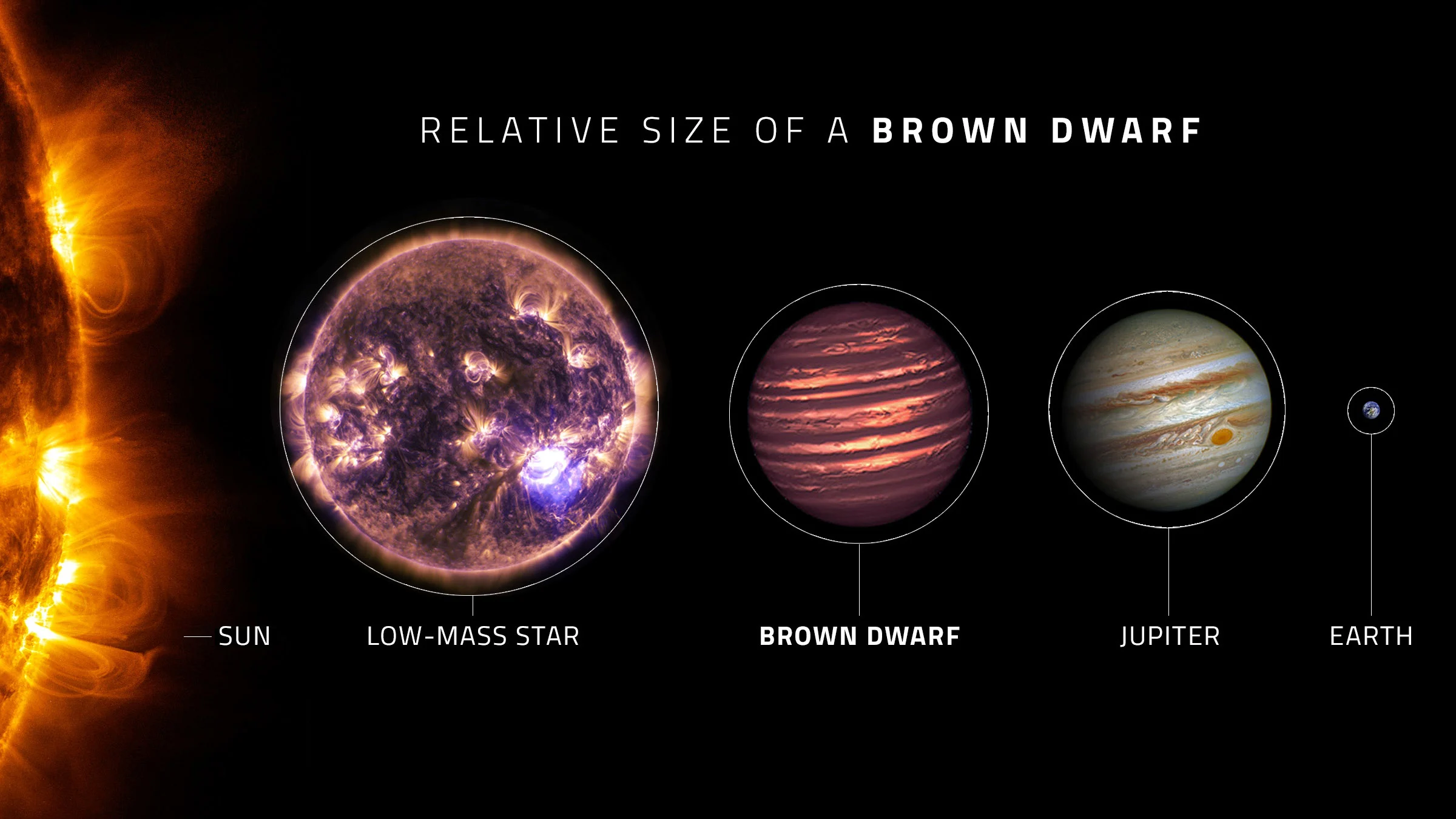

The upper limit — 13 times the mass of Jupiter — is the mass of the smallest brown dwarfs.

This infographic shows the relative sizes of different objects in space, from a star like our Sun, to a low-mass star, a brown dwarf, a gas giant planet (Jupiter), and a small rocky planet (Earth). While this brown dwarf appears to be only slightly larger than Jupiter, it compacts at least 13 times the mass of Jupiter into that space. (NASA/ESA/A. Simon, NASA GSFC, Canadian Space Agency)

Meanwhile, the first clause expands the definition of 'planet' beyond the confines of our own solar system to include any object of the right mass that orbits another stellar object. Currently, that would include every single exoplanet we've discovered so far.

No 'justice' for Pluto

On the down-side, this new definition would not grant the status of planet to any additional objects in our solar system, beyond the eight major planets.

Therefore, it's unlikely that we'll see Pluto's planetary status reinstated anytime soon.

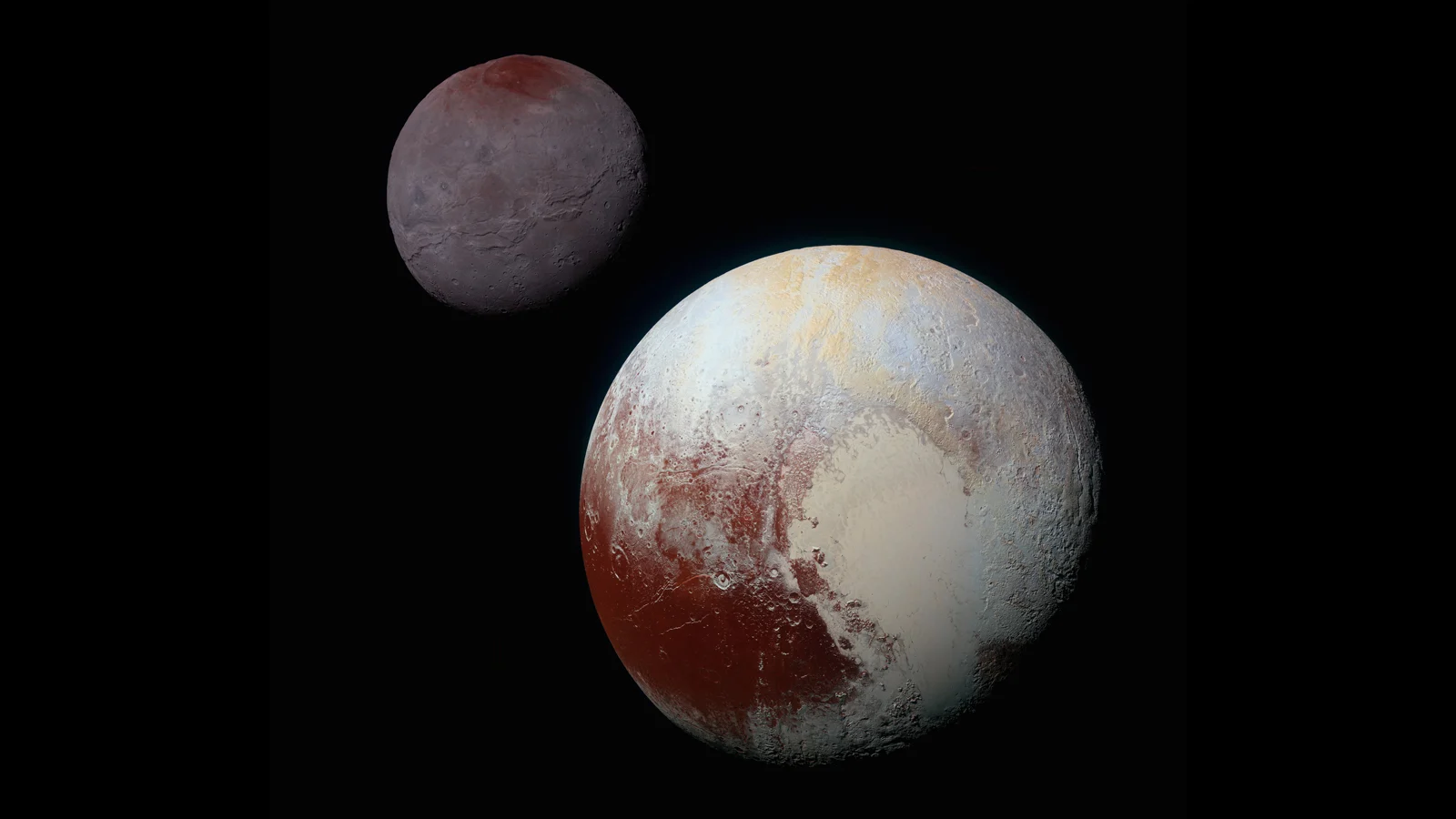

Pluto and its largest moon Charon, as shown here in images taken by NASA's New Horizons mission in 2015. Images such as these have caused many to question Pluto's demotion from planet status. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

As shown above, Pluto's mass is certainly large enough for it to have formed into a spherical shape. However, it is not massive enough to be dynamically dominant of its orbit.

"All the planets in our solar system are dynamically dominant, but other objects, including dwarf planets like Pluto, and asteroids, are not," said Dr. Margot.

Other definitions

This isn't the only time that scientists have suggested a different definition for what a planet is.

One proposal put forth would even completely remove the need for a planet to orbit around a star or other stellar object.

In 2002, planetary scientists Alan Stern and Harold Levison suggested that planetary status should only depend on the object being massive enough to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium, but below the mass needed for an object to generate energy in its core due to nuclear fusion.

Specifically, within our own solar system, this definition would increase the number of planets significantly.

Joining the eight major planets, would be nine dwarf planets — Pluto, Ceres, Eris, Sedna, Orcus, Haumea, Quaoar, Makemake, and Gonggong.

It would also add nineteen planetary-mass moons: Earth's Moon, four of Jupiter's moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto), seven of Saturn's moons (Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, and Iapetus), five of Uranus's moons (Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon), plus Neptune's moon Triton, and Pluto's moon Charon.

In addition, this definition would have included all exoplanets around other stars, as well as all rogue planets that are travelling alone through space after being expelled from their original star system.

The overall justification for including such diversity in planets was due to these objects all having value for studying planet formation. Titan has a substantial atmosphere. Europa has more water than Earth. Thanks to New Horizons, we know that Pluto's geology — even though it primarily involves ice — is incredibly varied, and it has fascinating atmospheric dynamics.

Perhaps during the coming conversation, some of these ideas will find their way into the final definition for 'planet'. Thus, the term may end up applying not only to objects outside our solar system, but to far more objects within our solar system as well.

(Note: a previous version of this article mistakenly stated that IAU general assemblies are annual events. They are, in fact, triennial. Thank you to Dr. Jean-Luc Margot for the correction.)