Rare 'Earthgrazer' put on a show over Europe before escaping back into space

This 'lucky' meteoroid was spotted only due to the presence of a Global Meteor Network camera

Meteors can be spotted flashing through the night sky almost every night of the year. In late September 2020, a special one - a rare 'Earthgrazer' - was captured over northern Europe.

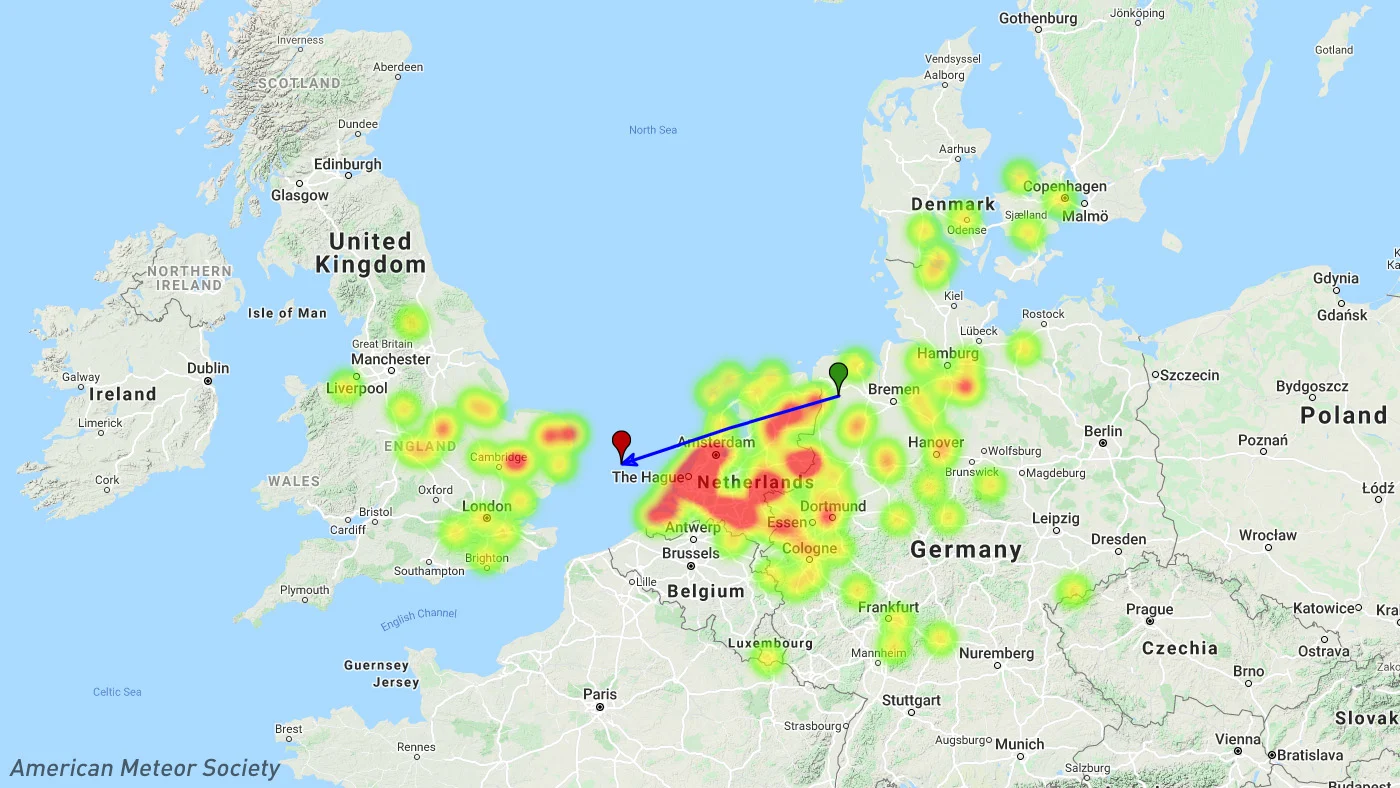

On the night of September 22, cameras and observers along a 750 kilometre-long swath of northern Europe witnessed a fantastic sight - a meteor flashed through the sky above, travelling at over 100,000 kilometres per hour. According to the American Meteor Society, 134 reports were submitted, from across southern Sweden, Denmark, northern Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and southern parts of the United Kingdom.

This map shows the concentrations of the eyewitness reports and the trajectory of the fireball from this Earthgrazer. Another map from the UK's System for Capture of Asteroid and Meteorite Paths (SCAMP) indicates that the trajectory likely reached all the way to Oxford or Swindon, to the west of London, UK. Credit: American Meteor Society

This was no ordinary meteor, though. Sure, it was a bright fireball, which attracted a lot of attention, but there was something extraordinary about this one.

It was an 'Earthgrazer'.

The flashes of light we call meteors are caused by bits of rock, ice or dust - collectively known as 'meteoroids' - that are swept up by Earth as we travel around the Sun. Most meteoroids plunge into the atmosphere at such an angle that it becomes the end of their journey. Smaller ones make a brief flash and completely burn up. For larger ones, pieces of them fall to the surface, for us to (maybe) find later, as meteorites.

In rare instances, the timing of the meteoroid's encounter with Earth is just right that it only skims through the highest, thinnest portion of the atmosphere. While it can still compress enough air molecules to emit a meteor flash, the air is too thin to slow it down significantly. Rather than burning away or plunging to the ground, it pops right back out of the atmosphere and continues on its journey through space. These are the Earthgrazers.

Four views of this Earthgrazer, captured by GMN cameras. Credit: Global Meteor Network

Dr. Denis Vida, a meteor physics postdoc at Western University who coordinates the Global Meteor Network, says the meteoroid may be a small piece of some unknown comet. This is based on the amount of fragmentation they saw as it travelled across the sky, as well as the orbit they traced it back along.

As for how big this meteoroid was, according to Vida, an estimate would be reasonably straightforward, if this had been a 'normal' meteor. In that case, it only takes knowing the speed it was travelling at and the total amount of light it produced before it burned out. Plug those values into some fairly simple physics equations, and out pops your answer.

"Estimating the size of an earthgrazer is trickier, as only a part of the mass is converted into light," Vida said in an email to The Weather Network. "The rest of what is now a charred rock returned back into space."

Vida's best estimate is that it was probably at least a centimetre across, and possibly up to 10 centimetres wide. Knowing with any greater accuracy would take "crunching some scary differential equations," Vida said.

RELATED: FIREBALL STREAKS ACROSS SOUTHERN ONTARIO

CITIZEN SCIENTISTS WANTED

One of the most significant limitations to observing and studying fireballs and meteors is the very small amount of the night sky covered by cameras that can capture them.

We do live in a world where the number of cellphone cameras and dashcams appears to be ever-increasing. However, most cameras are focused on what's happening on the ground, not high up in the sky.

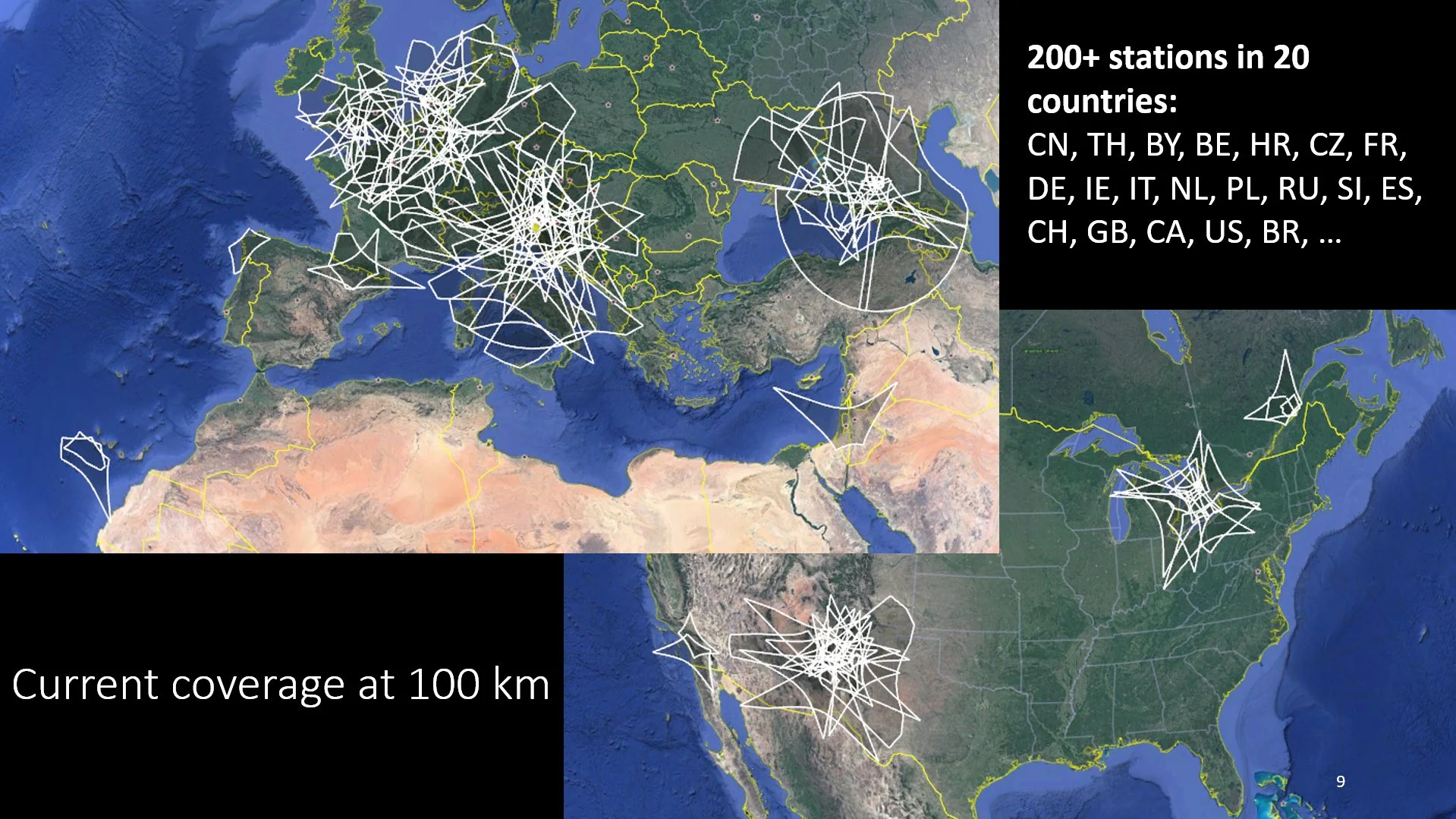

The Global Meteor Network is a project Vida coordinates in his spare time. It links together over 200 cameras, operated by amateur astronomers and citizen scientists across 20 different countries, to capture as many meteors as is possible. "No meteor unobserved" is their motto.

globalmeteornetwork.org. Credit: GMN

"The network is basically a decentralized scientific instrument, made up of amateur astronomers and citizen scientists around the planet each with their own camera systems," Vida explained in a European Space Agency news release.

"We make all data such as meteoroid trajectories and orbits available to the public and scientific community, with the goal of observing rare meteor shower outbursts and increasing the number of observed meteorite falls and helping to understand delivery mechanisms of meteorites to Earth."

Currently, very little of the Earth's night skies are actually covered by these cameras, though.

These maps showing the sky coverage of the Global Meteor Network were presented by Vida during the 2020 virtual International Meteor Conference. Credit: Denis Vida/GMN

Part of the issue with obtaining greater sky coverage has been the cost of cameras sensitive enough to capture meteor images for scientific research.

"One of the major goals of the Global Meteor Network is to bring the price of a meteor system down to the $100 price range," Vida said.

A pre-built, ready to use meteor camera is priced on the GMN website at around $700 Cdn. However, using the Network's instructions to build a meteor camera from scratch, the cost comes down to about $300.

An example meteor camera system. Credit: Denis Vida/GMN

Even with the amount of light pollution many of us deal with, living in urban or suburban areas, anyone can still become part of the network. The amount of light pollution may make it necessary to buy a better camera lens. However, the price difference is small (the 4mm lens that is optimal for "dark skies" is priced at just over $12, while the 8mm lens recommended for very light polluted skies is $16).

While the Network indeed produces some fantastic images for enthusiasts to pore over, the primary goal is to use the data they collect for scientific research. Participation in the network provides valuable resources for meteor scientists. As Vida points out, it can also connect amateurs and citizen scientists with professional astronomers who "are always on a lookout for prospective students."

"Finally, I expect this field to become increasingly important in the near future as space companies start launching more interplanetary missions and begin mining asteroids," Vida said. "Our atmosphere serves as a giant detector of meteoroids [from 30 microns up to 1 metre wide] which are otherwise invisible in space, but can be a big issue if they hit a spacecraft."

Sources: European Space Agency | Global Meteor Network | American Meteor Society