Rare Antarctic meteorite found by following satellite 'treasure map'

Of the roughly 45,000 meteorites found in Antarctica so far, only around 100 are this size or larger.

Guided by a 'meteorite treasure map', scientists have found an extraordinary specimen — one of the largest meteorites ever recovered from Antarctica.

Over the past two months, researcher Vinciane Debaille of the Free University of Brussels led a team of scientists across the barren terrain of Antarctica on a search for meteorites. Antarctica has long been considered an excellent spot to find space rocks. The cold, dry conditions preserve specimens for a long time, and their dark colour stands out quite well against the bright ice. Additionally, these treasures gather in specific regions, known as meteorite stranding zones, due to the effects of the weather and the movement of the ice.

Still, the Antarctic ice sheets represent an absolutely immense area to search!

So how did Debaille and her team know where to look? They followed a unique 'treasure map' that led them straight to a 7.6 kg (17 lb) meteorite, which is now one of the largest specimens ever found in that region of the world.

The scientists with the 7.6-kg meteorite they discovered. From left to right — White helmet: Maria Schönbächler. Green helmet: Maria Valdes. Black helmet: Ryoga Maeda. Orange helmet: Vinciane Debaille. Photo credit: Maria Valdes

Dr. Maria Valdes, from the Robert A. Pritzker Center for Meteoritics and Polar Studies at the University of Chicago's Field Museum, was one of the scientists on the expedition. In a Field Museum press release, she said that of the 45,000 meteorites recovered from Antarctica over the past century, only 100 or so have been of this size or bigger.

"Size doesn't necessarily matter when it comes to meteorites, and even tiny micrometeorites can be incredibly scientifically valuable, but of course, finding a big meteorite like this one is rare, and really exciting," Valdes explained.

According to the Field Museum, the team found five meteorites, which are being studied at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Along with these, the team members have divided up sediments gathered which may contain micrometeorites.

Valdes said that she is eager to see what they will learn from the specimens they recovered.

"Studying meteorites helps us better understand our place in the universe," she said in the press release. "The bigger a sample size we have of meteorites, the better we can understand our Solar System, and the better we can understand ourselves."

This close-up view of the 7.6-kg meteorite reveals the dark 'fusion crust' on its surface, as well as the lighter-coloured material exposed in areas where the crust has eroded away. Credit: Maria Valdes

Meteorite treasure map

Satellites reveal a lot about our planet. Now, thanks to their view from orbit, along with some very creative thinking by researchers and the power of machine learning, they have revealed where we can find treasures from space!

The map that Debaille, Valdes, and their colleagues followed in their trek across the Antarctic ice resulted from a study led by Veronica Tollenaar, a PhD student working with Debaille at the Free University of Brussels.

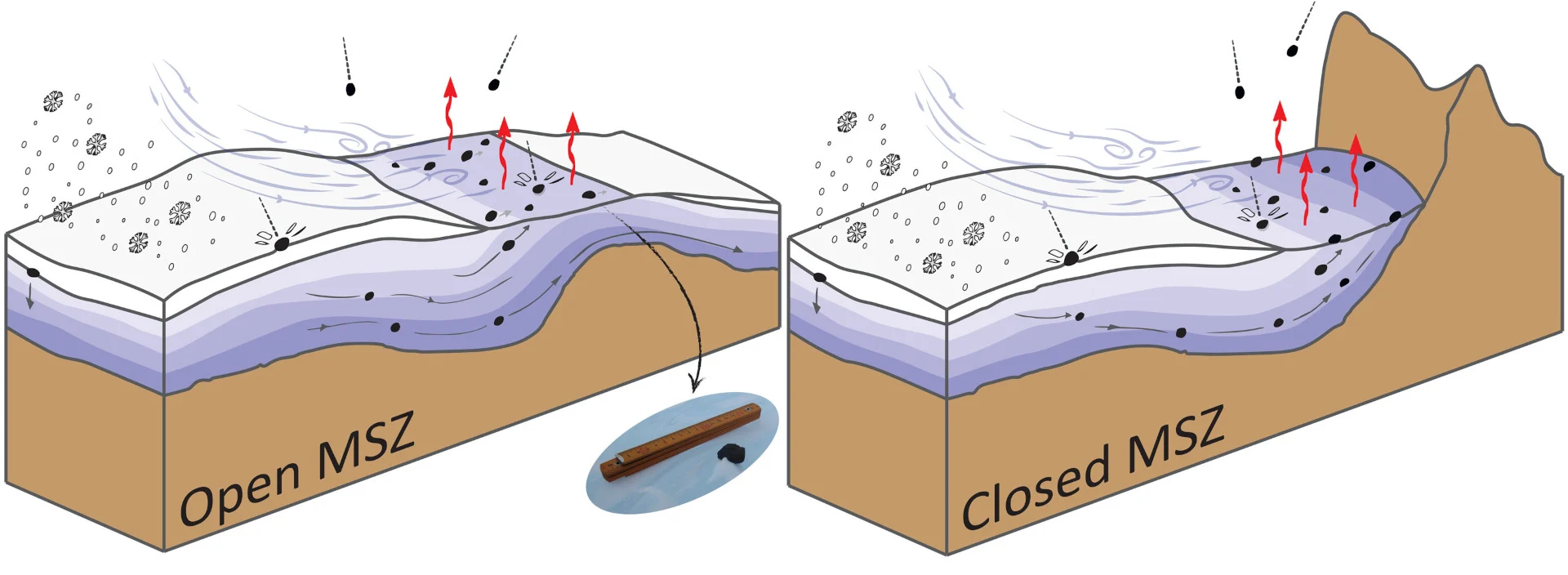

"When meteorites fall on the Antarctic, they typically lodge themselves within the ice sheet and drift toward the oceans," Tollenaar wrote in an article for The Conversation last year. "This has led some to describe ice as a 'natural conveyor belt' for meteorites. At times, mountains — occasionally hidden under the ice sheet — may come in their way and redirect them toward the surface of the ice sheet."

These two diagrams demonstrate how meteorite stranding zones develop. Credit: Tollenaar, et al./Science Advances

According to Tollenaar, meteorite stranding zones are reasonably easy to identify due to the blue-tinged ice exposed when the surface snow is blown away from these locations by the wind. While not all 'blue-ice areas' contain meteorites, those meteorites that have been recovered from Antarctica tend to be found in them.

To turn this knowledge into a 'meteorite treasure map', the researchers first combed through records of blue-ice areas that have been searched, separating them into those that contained meteorites and those that didn't. Noting the properties of each location — temperature, ice flow, surface cover, slope, etc. — they put computers to work identifying what combination of these properties made it more likely that meteorites would gather in those areas. Then, they applied that to other unexplored blue-ice areas to identify the most promising sites.

"Our research shows the accuracy of these predicted meteorite stranding zones is estimated to be over 80 per cent," Tollenaar said.

Now, just a year after their study was published, Tollenaar and her co-authors have had their research verified in the real world!