Saturn's 'Death Star' moon, Mimas, may be hiding a liquid water ocean

It may be the smallest of Saturn's major moons, but Mimas still had a surprise inside for researchers.

Saturn's moon, Mimas, appears to be harbouring a secret. Although once thought to be just a solid ball of ice, researchers have found evidence of an ocean deep under its surface.

Mimas has already gained some fame and recognition in the scientific community. As the innermost of Saturn's major moons, Mimas is positioned just outside the planet's ring system. From that vantage point, as its gravitational pull disturbs the particles in the rings, it clears out the dark band located between the two parts of the rings, known as the Cassini Division.

Icy Mimas appears to hover over Saturn's rings. The dark gap in the ring system, the Cassini Division, results from Mimas' gravitational pull on the ring particles. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

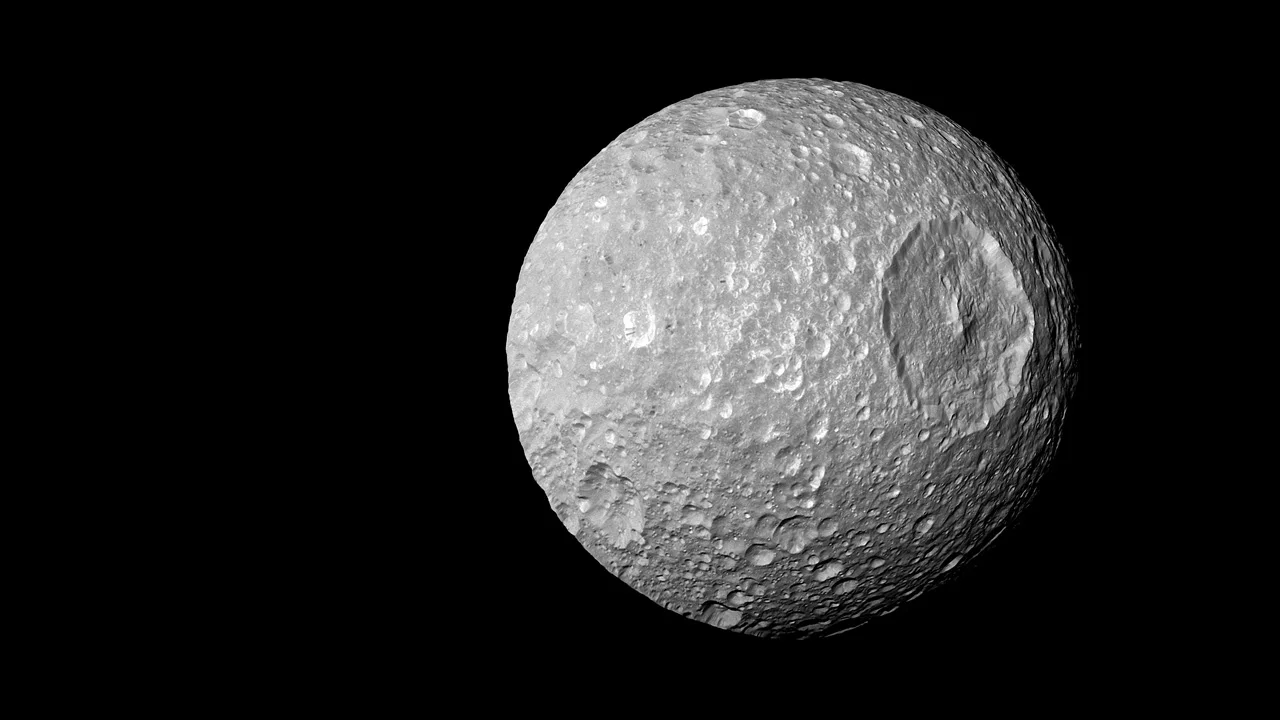

It has also gained some internet notoriety. Images sent back by Cassini revealed the immense impact remnant named Herschel Crater. Just the sight of this earned Mimas the nickname the Death Star moon.

This image of Mimas, taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft on February 13, 2010, reveals a closeup of its cratered surface, including Herchel Crater, which bears a distinct likeness to a well-known cinematic Space Station. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

One of the intriguing details about this small icy moon is that it presented scientists with a mystery.

Multiple images from Cassini's 13-year mission at Saturn revealed that Mimas 'wobbles' slightly as it orbits. This motion is known as libration, and it is caused by the gravitational interaction between Mimas and Saturn.

However, back in 2014, researchers noticed that part of this wobble couldn't be explained just by the direct influence of Saturn. Two explanations for this 'extra' motion were presented as the most likely. The first was that the moon's core is shaped like a football, and thus the gravitational pull between the planet and moon changes as the moon's orientation changes. The second was that Mimas' icy shell was actually shifting around its core, sliding atop a subsurface ocean of liquid water.

According to a press release by the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Dr. Alyssa Rhoden, a specialist in icy satellites at SwRI, was leading a team to take a closer look at Mimas. The intent was to show that the tiny, heavily cratered moon was just an inactive hunk of ice. But, instead, her team discovered compelling evidence that Mimas is an interior water ocean world, or IWOW. Despite its size and appearance, it really did look like there was an ocean of liquid water deep under Mimas' surface.

"Because the surface of Mimas is heavily cratered, we thought it was just a frozen block of ice," Rhoden said in the press release. "IWOWs, such as Enceladus and Europa, tend to be fractured and show other signs of geologic activity. Turns out, Mimas' surface was tricking us, and our new understanding has greatly expanded the definition of a potentially habitable world in our solar system and beyond."

This composite image shows colour photographs of Saturn's moons Mimas and Enceladus, taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Enceladus shows obvious signs of a subsurface ocean - a cracked, nearly crater-free surface, as well as plumes of water vapour that stream out near its south pole. Mimas, by comparison, presents only a few clues to the presence of its interior ocean. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI/Scott Sutherland

"If Mimas has an ocean," Rhoden said, "it represents a new class of small, 'stealth' ocean worlds with surfaces that do not betray the ocean's existence."

So, with the results found by Rhoden and her team it appears that Mimas can now join the list of other IWOWs we've found in our solar system. This list already includes fellow Saturnian moons Enceladus and Titan, along with Jupiter's Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, and possibly even Neptune's largest moon, Triton. Based on what we saw from the New Horizons probe, even Pluto may be on it.

Finding a subsurface ocean on Mimas provides us with more clues to how the moon formed, and it adds to our knowledge of the Saturn system. It may also indicate that we have been too narrow in our focus for where to look for these ocean worlds.

"Evaluating Mimas' status as an ocean moon would benchmark models of its formation and evolution," Rhoden said. "This would help us better understand Saturn's rings and mid-sized moons as well as the prevalence of potentially habitable ocean moons, particularly at Uranus. Mimas is a compelling target for continued investigation."