Is Greenland's ice hiding a second meteorite impact crater?

Just a few months after scientists reported discovering an immense impact crater in northern Greenland, it looks like they may have found a second one!

Scientists exploring the depths of the Greenland ice sheet were hoping to unlock the secrets of the island that lay underneath the ice, and it seems as though they've succeeded in uncovering a couple of amazing ones!

In a new study published this week, researchers with NASA's Operation IceBridge are reporting that they may have found a second giant impact crater, hidden away under the ice of northern Greenland.

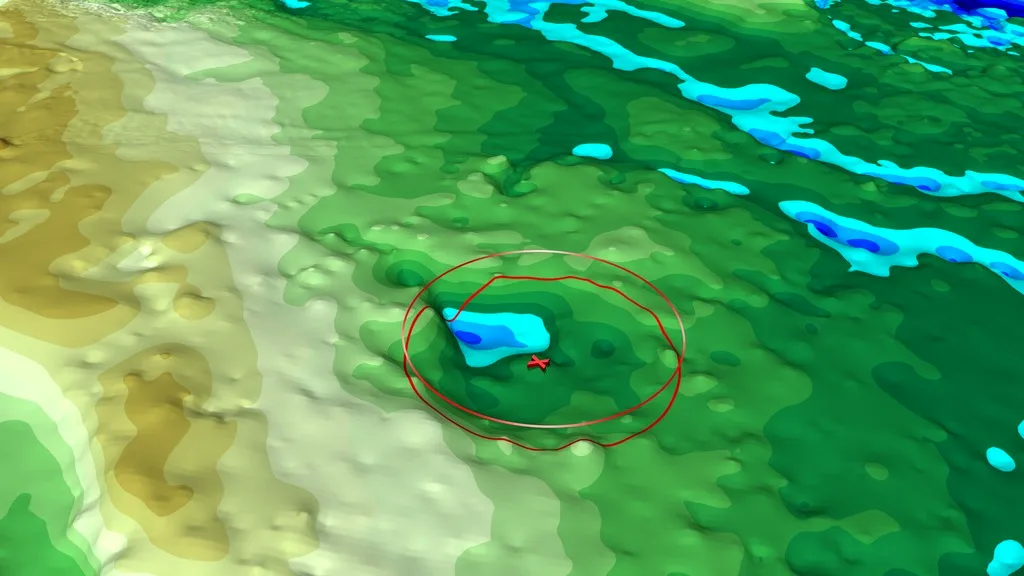

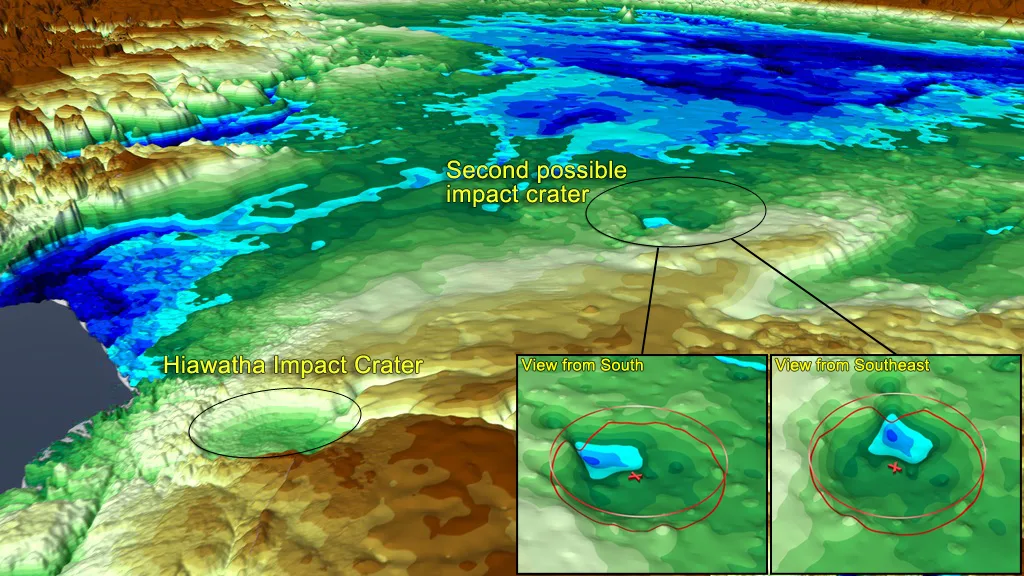

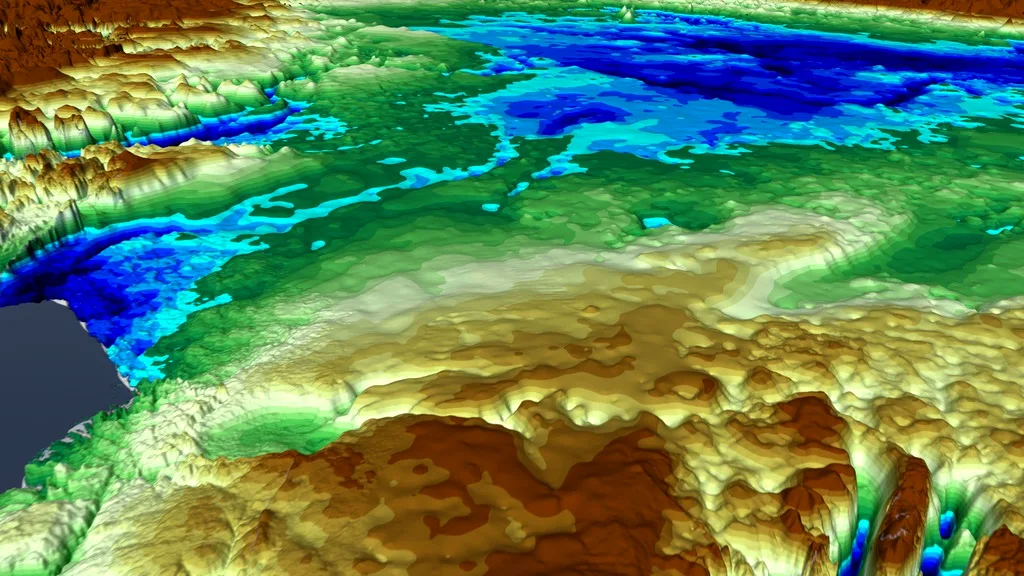

The Haiwatha crater and this second crater, are shown in this NASA computer simulation of the IceBridge ice-penetrating radar data. Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio/Scott Sutherland

The discovery of the 31-kilometre-wide Hiawatha impact crater was announced back in November of 2018. Located at the edge of the ice sheet, near the coastline, it was discovered by an international team of scientists that used Operation IceBridge ice-penetrating radar data to identify what appeared to be a crater rim preserved under the kilometre-thick glacier ice.

This was something of a surprise when it was revealed, since the assumption was that impact craters in places like Greenland and Antarctica would be lost due the intense pressure of billions of tonnes of moving ice scouring them away. So, finding that one of these craters had possibly survived was unexpected, to say the least.

While those findings did point to the potential that Hiawatha could be a fairly young crater, according to NASA glaciologist Joe MacGregor, it got him thinking about whether other craters might be lurking under the ice, just waiting to be found.

According to NASA and the American Geophysical Union:

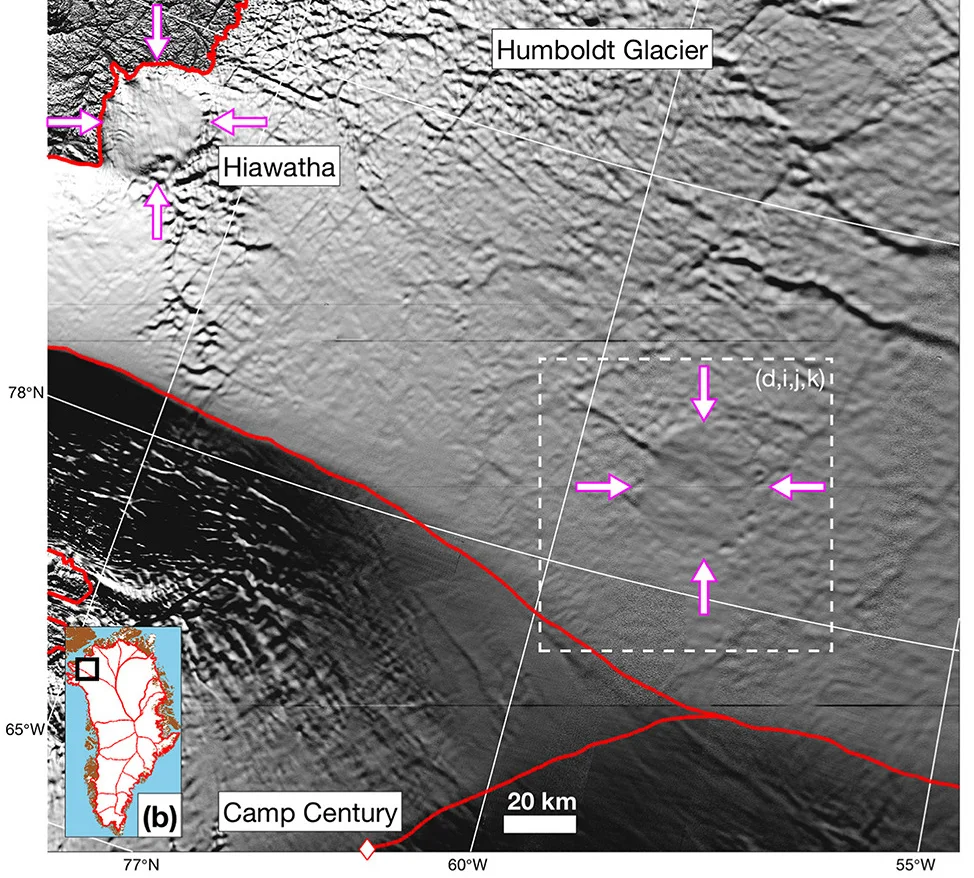

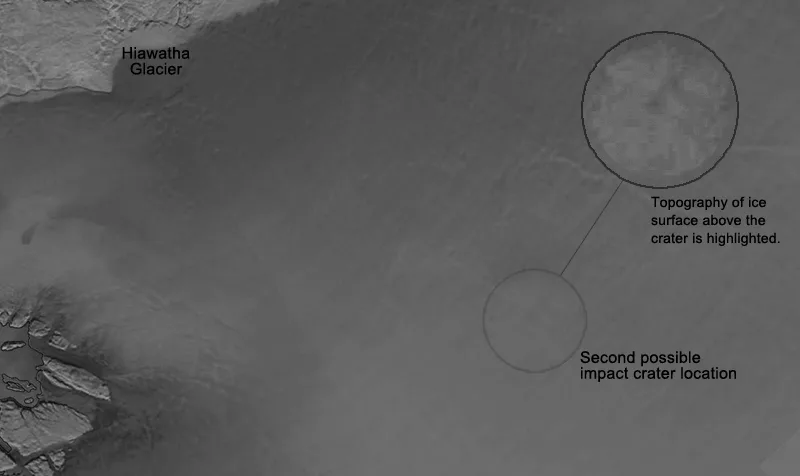

Following the finding of that first crater, MacGregor checked topographic maps of the rock beneath Greenland’s ice for signs of other craters. Using imagery of the ice surface from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer instruments aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, he soon noticed a circular pattern some 114 miles to the southeast of Hiawatha Glacier. The same circular pattern also showed up in ArcticDEM, a high-resolution digital elevation model of the entire Arctic derived from commercial satellite imagery.

"I began asking myself 'Is this another impact crater? Do the underlying data support that idea?'," MacGregor told NASA and the AGU. "Helping identify one large impact crater beneath the ice was already very exciting, but now it looked like there could be two of them."

This newly discovered, as-of-yet unnamed potential crater is roughly 180 kilometres to the southeast of Hiawatha, and is slightly bigger, with an apparent diameter of around 35 kilometres.

Satellite view of the Hiawatha crater (upper left), and the position of the new potential impact crater identified by the new study. Credit: MacGregor et al., using Arctic DEM data from University of Minnesota

Satellite view of this same region from the VIIRS instrument of NASA's Suomi NPP satellite. The region of the newly discovered crater is highlighted. Credit: NASA Worldview/Scott Sutherland

IS THIS REALLY AN IMPACT CRATER?

There is still some uncertainty surrounding this discovery, so at the moment there's no way to say, conclusively, that this is an impact crater or it isn't an impact crater.

NASA's topographical map of the Hiawatha crater (lower left) and this new crater (right of centre). Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio

Hiawatha is certainly a much better candidate for an impact crater. Just glancing at it, it looks like what you'd expect to see for an impact crater, with a very obvious steep-sided rim, flat base and central peaks. Still, even so, there is a chance that Hiawatha is left over from some other process or collection of processes.

For this new candidate, it is even more difficult to say. The ice feature at the surface is more difficult to pick out, compared to Hiawatha's, and the depression appears similar to many of the other depressions in the Greenland bedrock.

So, if it wasn't actually an impact crater, though, what could it be?

"The only other circular structure that might approach this size would be a collapsed volcanic caldera," MacGregor said in the NASA/AGU press release. "But the areas of known volcanic activity in Greenland are several hundred miles away. Also, a volcano should have a clear positive magnetic anomaly, and we don't see that at all."

According to the study, what this crater does have is a 'negative gravity anomaly', meaning that the surface is depressed (pushed down), relative to the surrounding bedrock. This is characteristic of impact craters. Negative gravity anomalies are also known to be associated with glaciers, but specifically in areas that once had glaciers, long, long ago. Due to the presence of Greenland's current ice sheet, the island has an overall positive gravity anomaly, because the mass of the ice adds to the gravity of the area.

One possible reason for why this crater does not share the same 'look' of an impact crater that Hiawatha has, is that is has gone through much more weathering and erosion, by comparison. According to the study, the ice over the crater is much thicker, and it is much older, than the ice of the Hiawatha glacier. This thicker ice may have eroded the crater faster, or if the crater formed earlier than the Hiawatha crater, there would have simply been more time for erosion to take its toll.

Sources: AGU | NASA | University of Minnesota