What's up in space for Spring 2020? Find out here!

Meteor showers, supermoons and a 'planetary dance'

Spring can be an excellent season for stargazing, as the night air still tends to be stable, but temperatures warm enough to make it easier to stay outside.

Starting off Spring 2020, look up to the early morning skies, just before dawn, for a lineup of planets in the southeastern sky.

Over a period of 13 days, Jupiter, Saturn and Mars perform a little 'dance', morning-by-morning, with Mars starting on March 20 paired with Jupiter, and then sauntering over to Saturn by the 1st of April.

Jupiter, Saturn and Mars can be seen in the predawn sky throughout the season, but from March 20 - April 1 they will put on an extra special display as Mars migrates from a Jupiter conjunction to a Saturn conjunction, day by day. The two panels above show the beginning and end of this planetary 'dance'. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

This grouping of planets is set up to repeat itself - with slight differences - throughout the coming seasons. It will culminate on the first day of Winter, with a Great Conjuction, where Jupiter and Saturn appear to touch in the evening sky.

Visit our Complete Guide to Spring 2020 for an in-depth look at the Spring Forecast, tips to plan for it and much more

SPRING ASTRONOMY 2020

March 20-April 1: Saturn and Jupiter dance with Mars

April 7-8: Super Pink Moon

April 14-16: Moon sweeps past Jupiter, Saturn and Mars

Apri 21-22: Lyrid Meteor Shower (near New Moon)

May 6-7: eta Aquarid Meteor Shower (near Full Moon)

May 12-15: Moon sweeps past Jupiter, Saturn and Mars again

June 8-13: Moon sweeps past Jupiter, Saturn and Mars one more time

June 19: Moon occults Venus in predawn sky

June 20: Summer Solstice

BONUS June 21: Annular Solar Eclipse (Africa, India, China)

PLANET-MOON CONJUCTIONS

Throughout Spring, the brightest planets in the sky will continue to put on the morning shows we saw in Winter, and the Moon will be joining them as well.

Jupiter, Saturn and Mars are lined up in the predawn sky on April 15, with the Waning Gibbous Moon nearby. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Watch for the Moon to sweep past these three planets in mid-April, mid-May and mid-June.

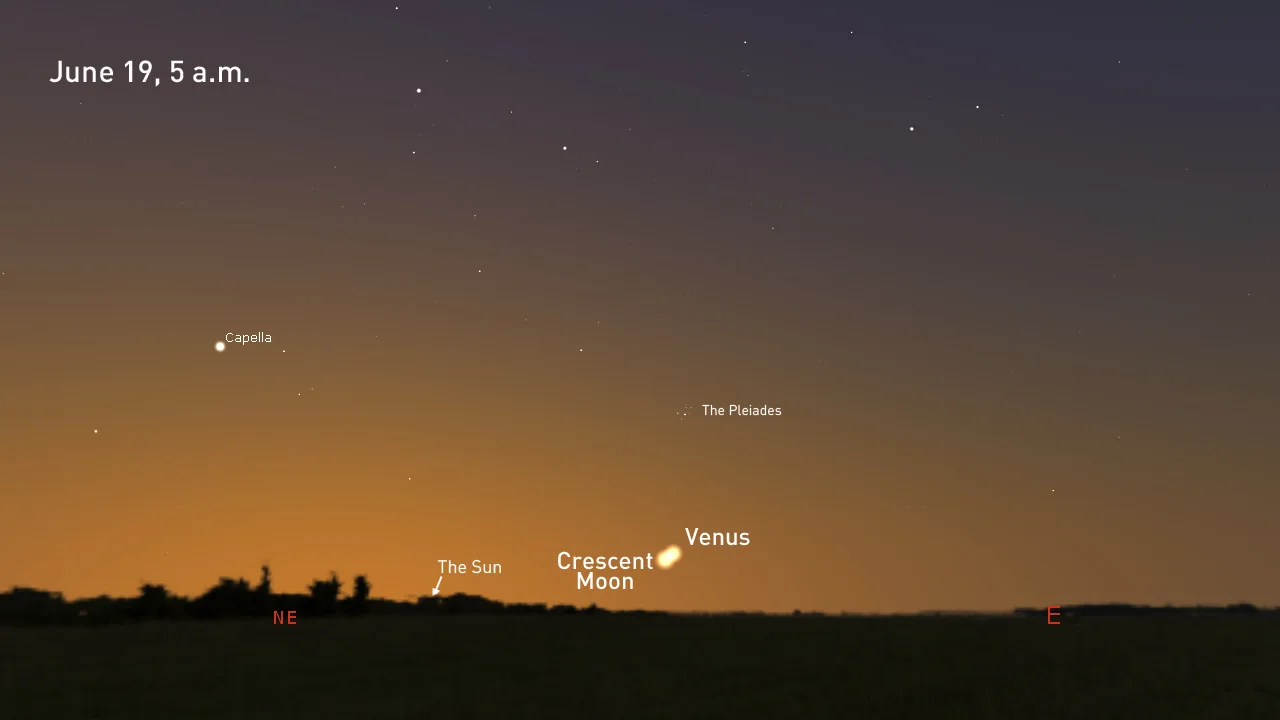

Venus will prove to be quite elusive this season, as we mostly lose sight of it in the daytime sky. Keep a close eye on the predawn sky late in the season, though, specifically on June 19. Before the Sun rises, Venus can be spotted very near the eastern horizon, and very close to an extremely thin Crescent Moon.

A view of the predawn sky on June 19, with Venus and the Crescent Moon nearly touching. In some areas, viewers will see the Moon occult Venus. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Viewers in northern and eastern Canada may see Venus pass behind the Moon, in an astronomical alignment known as an occultation.

SUPER (PERIGEE) PINK MOON

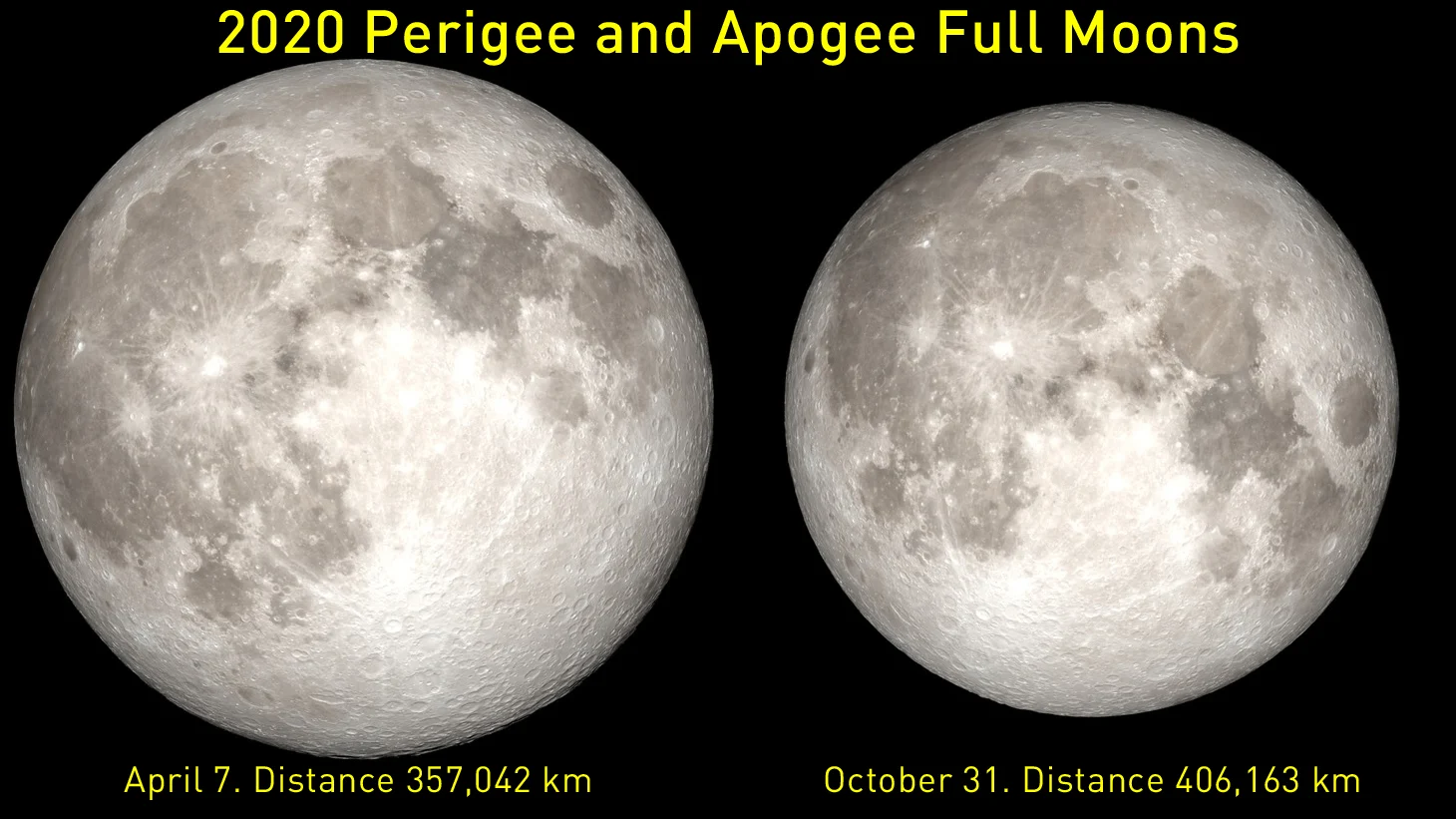

There are a sum total of four 'Super' Moons in 2020 - Full Moons that are exceptionally close and bright. The one that rises on the night of April 7 promises to be the best of them!

The April 7-8 Full Moon is what's known as this year's 'Perigee Full Moon' - the closest Full Moon of the entire year.

A comparison of the closest and farthest Full Moons of 2020. Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio/Scott Sutherland

It is not easy to tell that the Moon looks about 14 per cent bigger in the sky that night. It will be much easier, however, to notice that it is around 30 per cent brighter than usual!

LYRID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

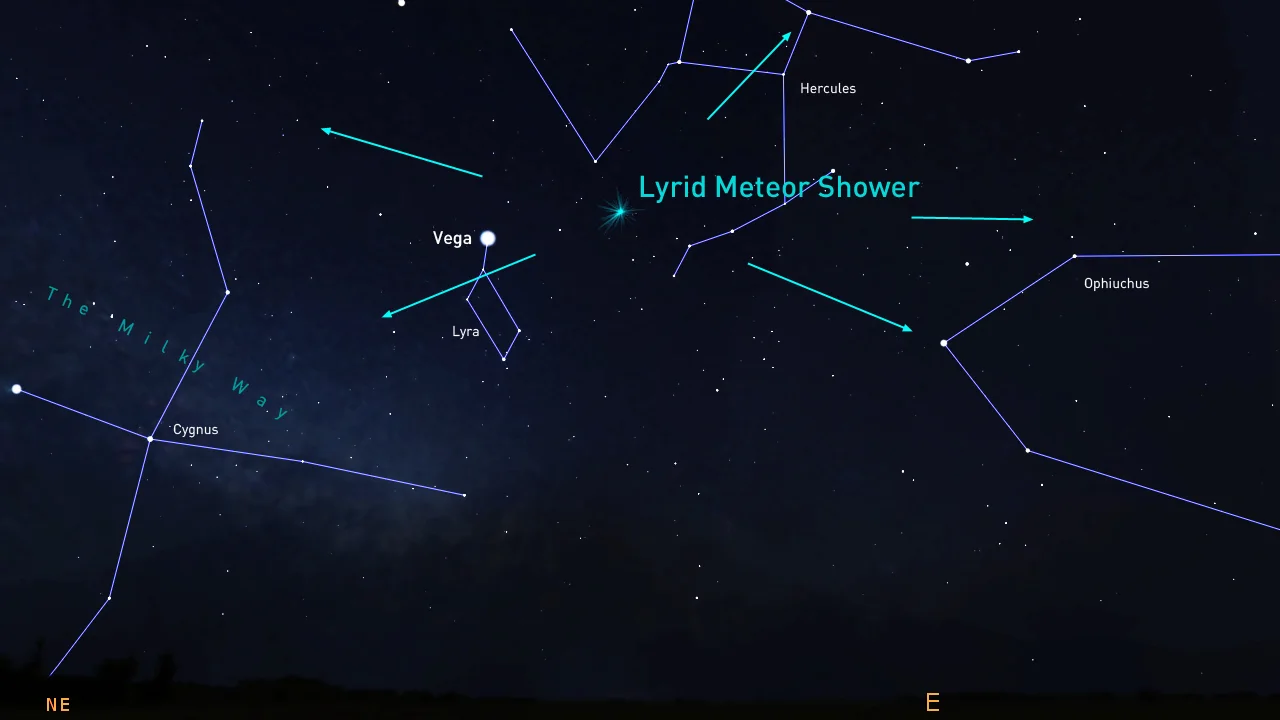

Two major meteor showers occur in springtime, and this year, the April Lyrids are definitely the one to watch.

Timed perfectly on the night of April 21-22, so that the peak of the shower happens the night before the New Moon, there will be no competing sources of light in the sky.

The radiant of the Lyrid meteor shower, at midnight on the night of April 21-22. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The 'radiant' of this meteor shower - the point in the sky where the meteors appear to originate - rises in the east as the Sun sets on April 21, and it tracks across the night sky towards dawn.

Lyrid meteors originate from a stream of dusty, icy meteoroid debris left behind by Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher. The bright streaks we see across the sky occur when Earth passes through that stream, and the atmosphere 'sweeps up' some of that dust and ice. Travelling at around 100,000 km/h, these tiny meteoroids compress the air in their path until that air glows white-hot. This meteor flash goes out either when the 'push-back' from the atmosphere slows the meteoroid, or the meteoroid completely vaporizes.

The stream of debris from Comet Thatcher is relatively sparse, so even at the shower's peak, the Lyrids only deliver around 20 meteors per hour. Many viewers will only see about half that number.

Embedded within the stream, however, are some larger meteoroids, and when those hit the atmosphere, they produce bright fireballs!

The Lyrid radiant is up all night, so we can view this shower at any time after sunset (provided the weather is good). The best time to watch, though, is typically in the hours between midnight and dawn. This is when the sky is at its darkest, and be sure to get away from city light pollution to get the best show.

ETA AQUARIID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

Comet Halley is probably the most well-known comet in the world, passing by our planet and putting on a spectacular show every 75 years. Perhaps less well-known is the fact that it is the only comet we know of that produces two major meteor showers each year!

The eta Aquariids, which peak on the night of May 5-6 this year, is the first of these two Comet Halley meteor showers.

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, in the hours before dawn, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The best time to see the eta Aquariids is in the hours before dawn on May 6, since the radiant only rises above the eastern horizon at that time.

This year is not ideal for the eta Aquariids, due to how soon dawn arrives after the radiant rises, and due to the presence of a nearly Full Moon.

The eta Aquariids typically produce around 50 meteors per hour under ideal conditions (clear, dark sky, with the meteor shower radiant directly overhead). Most observers will likely see a couple of dozen per hour, but possibly more depending on sky conditions. This shower does not tend to produce bright fireballs, as the Lyrids do. The meteoroids are moving so quickly when they hit our atmosphere, however, that they can produce a phenomenon called persistent trains.

Watch below to see a persistent train from a different meteor shower

When a typical cometary meteoroid hits the top of Earth's atmosphere, it is moving fast enough to produce a meteor flash (as mentioned above). The particles in the eta Aquariid stream, however, hit Earth's atmosphere travelling at nearly two and a half times as fast!

Streaking through the air at 240,000 km/h, Comet Halley meteoroids produce the usual brief meteor flash, but they can also result in a bonus. Once the meteor goes out, a glowing trail is left behind, floating in the air, called a persistent train. Some persistent trains last for minutes after the meteor flash, while others remain visible for hours.

Since persistent trains have only rarely been recorded, scientists still aren't quite sure what causes them. There are two basic ideas that could explain them, though.

The first is that the meteoroids are travelling fast enough to strip electrons from the air molecules, leaving them in an ionized state. As the air molecules snatch up electrons from their surroundings, they release energy in the form of light. Since this process can take much longer than the original meteor flash, the 'train' appears fainter, and it can persist for some time after the meteor flash ends.

The other idea involves what is known as 'chemiluminescence'. Metals vaporizing off the surface of the fast-moving meteoroids can chemically react with ozone and oxygen in the air, to produce a glow.

One of these explanations may account for these 'trains', or both may cover different occurrences, at different times, and even between individual meteors. It will take more sightings of these to explain them fully.

SUMMER SOLSTICE

On June 20, at 21:44 UTC, the Sun will reach its highest point in the northern sky for 2020.

The June Solstice marks the start of Summer in the northern hemisphere and the start of Winter in the southern hemisphere.

It is also the longest day of the year for the northern hemisphere. Exactly how long will depend on where you live (and how close to the north pole you are). For example, Toronto will see 15 hours, 26 minutes and 32 seconds of daylight on this day. Edmonton, on the other hand, will see 17 hours, 2 minutes and 43 seconds of daylight.

BONUS: JUNE 22 ANNULAR SOLAR ECLIPSE

This event happens in Summer of 2020, but just two days after the solstice, an annular solar eclipse (very similar to the one from last December) will be taking place on the other side of the planet from Canada.

This image of an annular or 'ring of fire' eclipse was taken by Wikimedia user Nakae in 2012.

While we won't be able to see this directly from here, there will undoubtedly be live streams of the event for us to watch as it happens.

Sources: IMO | RASC | TimeandDate.com | With files from The Weather Network