Eyes to the sky for these amazing springtime astronomical events

There's still plenty to see in the sky this spring, but the upcoming total lunar eclipse is sure to be the 'star' of the season.

There are meteor showers to look forward to, planetary conjunctions, and even an Annular Solar Eclipse high in the Arctic. Get ready near the end of May, though, for the first total lunar eclipse visible from Canada in over two years.

QUICK LIST

March 20 — Equinox

March 20 — Mercury, Jupiter & Saturn, eastern horizon pre-dawn

March 28-29 — Worm Moon

March 30 — Zodiacal Light after evening twilight, western sky for two weeks

April 21-23 — Lyrid meteor shower peak

April 26-27 — Super Pink Moon

May 5-6 — eta Aquariid meteor shower peak

May 15 — Mars & Moon conjunction, western horizon after sunset

May 26 — Super Blood Flower Moon total lunar eclipse

May 28 — Mercury & Venus conjunction, western horizon after sunset

June 10 — Annular Solar Eclipse across the Arctic

June 12 — Venus, Moon & Mars, western horizon after sunset

June 21 — Solstice

Visit our Complete Guide to Spring 2021 for an in-depth look at the Spring Forecast, tips for planning for it and much more!

THE PLANETS

The night sky is filled with stars, especially if you find a viewing spot far from city lights. Even from the densest urban core, though, when all the stars are washed out by light pollution, some celestial objects remain visible. The Moon is one, of course, but a handful of planets can also be seen. Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are the most notable, with Mercury making a morning or evening appearance at times.

In the spring of this year, Jupiter and Saturn make their return to the night sky. After the Great Conjunction on the December Solstice, the two giant planets ducked behind the Sun. They are starting to come out again, now, visible along the eastern horizon just as the Sun, with Mercury hanging out with them, as well.

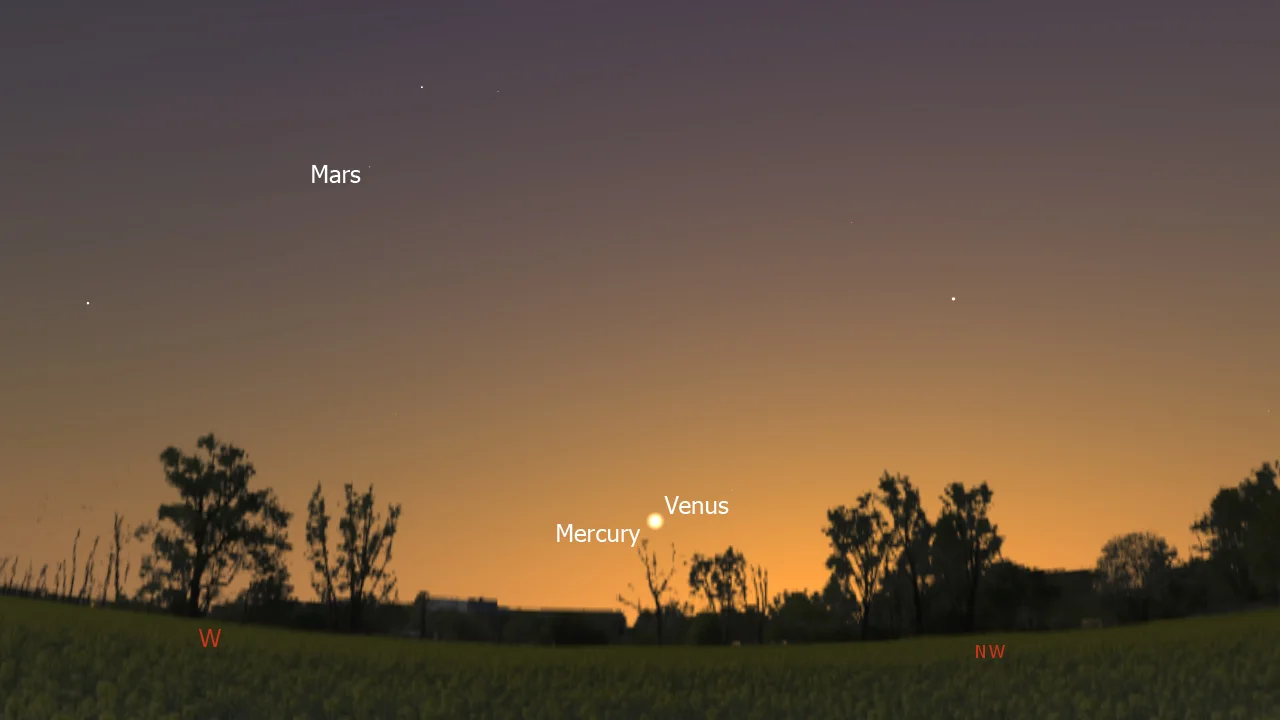

Three planets line up in the eastern sky, pre-dawn, on March 20, 2021. Credit: Stellarium

As the season progresses, the two will rise earlier and earlier, providing a much better look for pre-dawn stargazers.

Additionally, watch for Mars in the western sky throughout the season. Starting in early May and progressing through early June, Mars can be spotted along with Mercury and Venus. The Moon will swing past the trio on May 15. Then, watch as Mercury and Venus perform a celestial 'do-si-do' in late May, appearing to merge on the 28th.

The western horizon, just after sunset on May 28, 2021. Mars can be seen, very faintly in the twilight, while Mercury and Venus are close enough to appear to have merged. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

While Mercury moves on, the Moon returns to sweep past Venus and Mars on June 12.

THE ZODIACAL LIGHT

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: ESO

For about two weeks this spring, evening skywatchers can catch a glimpse of the immense cloud of interplanetary dust that encircles the Sun. This manifests in our night sky as a phenomenon known as The Zodiacal Light.

In the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 2021 Observer's Handbook, Dr. Roy Bishop, Emeritus Professor of Physics from Acadia University, wrote: "The zodiacal light appears as a huge, softly radiant pyramid of white light with its base near the horizon and its axis centred on the zodiac (or better, the ecliptic). In its brightest parts, it exceeds the luminance of the central Milky Way."

According to Dr. Bishop, even though this phenomenon can be quite bright, it can easily be spoiled by moonlight, haze or light pollution. Also, since it is best viewed just after twilight, the inexperienced sometimes confuse it for twilight and miss out.

On clear nights and under dark skies, look to the western horizon, in the half an hour just after twilight has faded, from about March 30 to April 13.

LYRID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

On the night of April 21-22, the Lyrid meteor shower reaches its peak. Active from April 14-30, the Lyrids show off their best activity on the three nights around its peak, according to the International Meteor Organization (IMO).

This year, although a waxing gibbous Moon is in the sky, it will be in the opposite end of the sky throughout the night. The peak is also timed for the early morning, pre-dawn hours, so after the Moon has set.

The radiant of the Lyrid meteor shower, at midnight on the night of April 21-22. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The 'radiant' of this meteor shower — the point in the sky where the meteors appear to originate — rises in the east as the Sun sets on April 21, and it tracks across the night sky towards dawn.

Lyrid meteors originate from a stream of dusty, icy meteoroid debris left behind by Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher. The bright streaks we see across the sky occur when Earth passes through that stream, and the atmosphere 'sweeps up' some of that dust and ice. Travelling at around 100,000 km/h, these tiny meteoroids compress the air in their path until that air glows white-hot. This meteor flash goes out either when the 'push-back' from the atmosphere slows the meteoroid enough, or the meteoroid completely vaporizes.

The stream of debris from Comet Thatcher is relatively sparse. Even at the shower's peak, the Lyrids only deliver around 20 meteors per hour. Many viewers will only see about half that number.

Embedded within the stream, however, are some larger meteoroids, and when those hit the atmosphere, they produce bright fireballs!

The Lyrid radiant is up all night, so we can view this shower at any time after sunset (provided the weather is good). The best time to watch, though, is typically in the hours between midnight and dawn. This is when the sky is at its darkest, and be sure to get away from city light pollution to get the best show.

ETA AQUARIID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

Comet Halley is probably the most well-known comet in the world, passing by our planet and putting on a spectacular show every 75 years. Perhaps less well-known is that it is the only comet we know of that produces two major meteor showers each year!

The eta Aquariids is the first of these two Comet Halley meteor showers. Active from around April 19 to May 28 each year, it peaks on the night of May 5-6 in 2021.

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, in the hours before dawn, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The best time to see the eta Aquariids is in the hours before dawn on May 6, since the radiant only rises above the eastern horizon at that time. Also, with only a waning crescent Moon at the time, there is little competing light for the meteors.

The eta Aquariids typically produce around 50 meteors per hour under ideal conditions (clear, dark sky, with the meteor shower radiant directly overhead). Most observers will likely see a couple of dozen per hour, but possibly more depending on sky conditions. This shower does not tend to produce bright fireballs, as the Lyrids do. The meteoroids are moving so quickly when they hit our atmosphere, however, that they can produce a phenomenon called persistent trains.

Watch below to see a persistent train from a different meteor shower

When a typical cometary meteoroid hits the top of Earth's atmosphere, it moves fast enough to produce a meteor flash (as mentioned above). However, the particles in the eta Aquariid stream hit Earth's atmosphere travelling at nearly two and a half times as fast!

Streaking through the air at 240,000 km/h, Comet Halley meteoroids produce the usual brief meteor flash, but they can also result in a bonus. Once the meteor goes out, a glowing trail is left behind, floating in the air, called a persistent train. Some persistent trains last for minutes after the meteor flash, while others remain visible for hours.

Since persistent trains have only rarely been recorded, scientists still aren't quite sure what causes them. There are two possible explanations, though.

The first is that the meteoroids are travelling fast enough to strip electrons from the air molecules, leaving them in an ionized state. As the air molecules snatch up electrons from their surroundings, they release energy in the form of light. Since this process can take much longer than the original meteor flash, the 'train' appears fainter, and it can persist for some time after the meteor flash ends.

The other idea involves what is known as 'chemiluminescence'. Metals vaporizing off the fast-moving meteoroid's surface can chemically react with ozone and oxygen in the air to produce a glow.

One of these explanations may account for these 'trains', or both may cover different occurrences at different times and even between individual meteors. It will take more sightings of these to explain them fully.

TOTAL LUNAR ECLIPSE

Remember the Super Blood Wolf Moon? It's been over two years since that amazing event, and we haven't seen another lunar eclipse like it in that time.

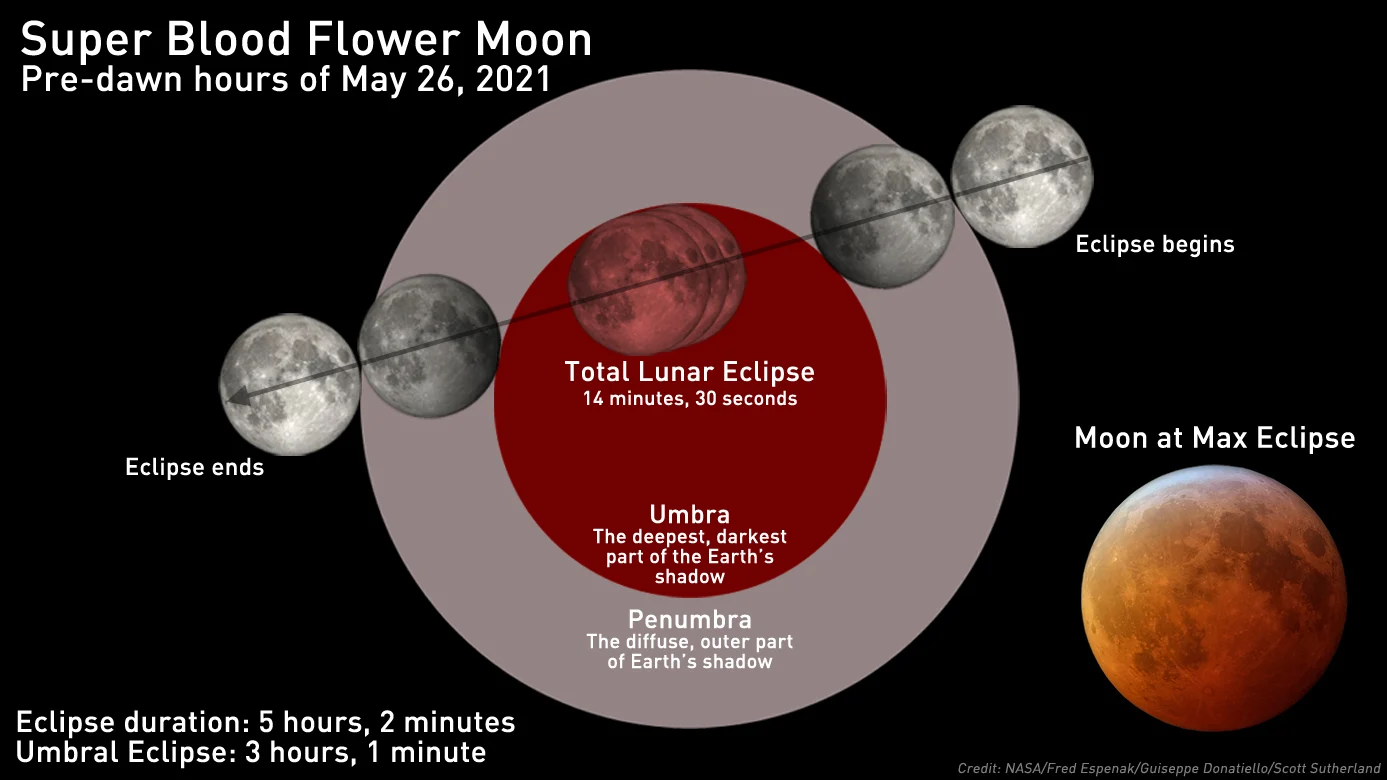

In the pre-dawn sky on May 26, 2021, however, the Sun, Earth and Moon will finally line up just right again to produce another perigee total lunar eclipse — the Super Blood Flower Moon.

The path of the Full Flower Moon through Earth's shadow during the May 26 total lunar eclipse. Inset closeup of eclipse (bottom right) combines NASA Goddard Visualization Studio image of the Moon at the eclipse peak with a photo of the 2019 Super Blood Wolf Moon by Guiseppe Donatiello. Credit: NASA/Fred Espenak/Scott Sutherland.

It's not quite as flashy a name. It's doubtful Stephen Colbert would have named his "Goth Dad Band" after it, or that it'll earn a song by Pearl Jam, but this is a notable one. At just 357,453 km from Earth during the eclipse, this is actually a slightly closer and slightly larger 'blood moon' than we saw in 2019.

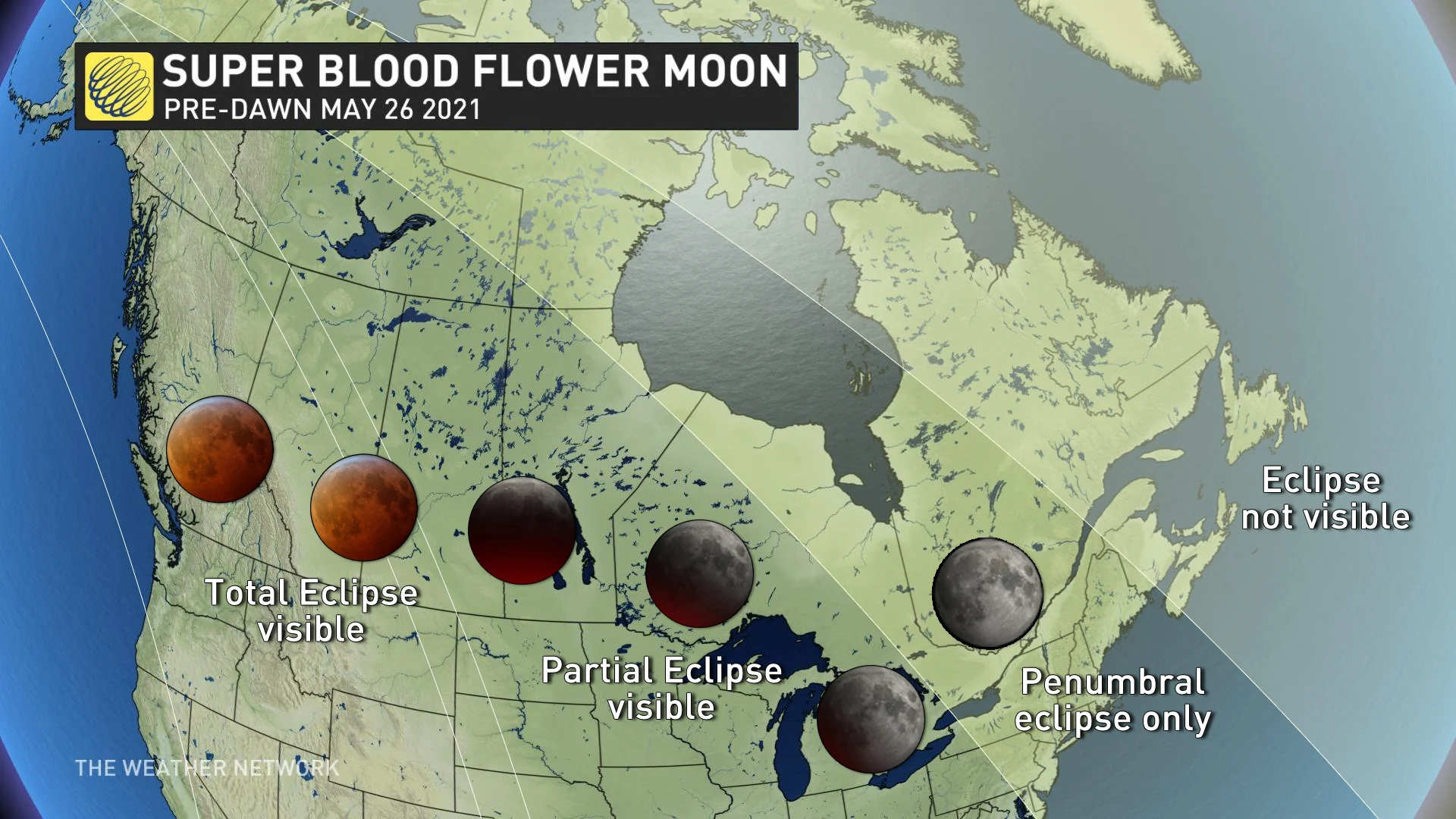

There's one unfortunate part to this event, though. Unlike the January 2019 eclipse, which was visible across the country, this eclipse is best viewed only from Western Canada. Some regions won't even see it.

Sunrise and moonset will end the event early for eastern regions of Canada, in some places before it even starts.

In Atlantic Canada, the Moon will have set by the time the eclipse even begins. In Quebec, and Eastern and Northern Ontario, only the penumbral eclipse will be visible before the Moon slips below the horizon. Those in Southwestern Ontario, including the Greater Toronto Area, will only see the Moon just begin its transition into the umbra before the Moon sets. Farther west, more and more of a partial lunar eclipse will be seen, but anywhere east of Regina, SK isn't going to see the total eclipse at all. The total lunar eclipse will be visible only from southwestern Saskatchewan, most of Alberta, and in British Columbia, either just at moonset or hanging low on the western horizon.

If you can't see it for yourself, the event is sure to be live-streamed from various locations across Canada and the United States. The Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles should have an exceptional view. The telescopes on top of Mauna Kea in Hawai'i will likely have the best view of all.

Don't miss it, though! This will be the last 'super' total lunar eclipse in over a decade. The next one will be the Super Blood Harvest Moon in October 2033.

ANNULAR SOLAR ECLIPSE

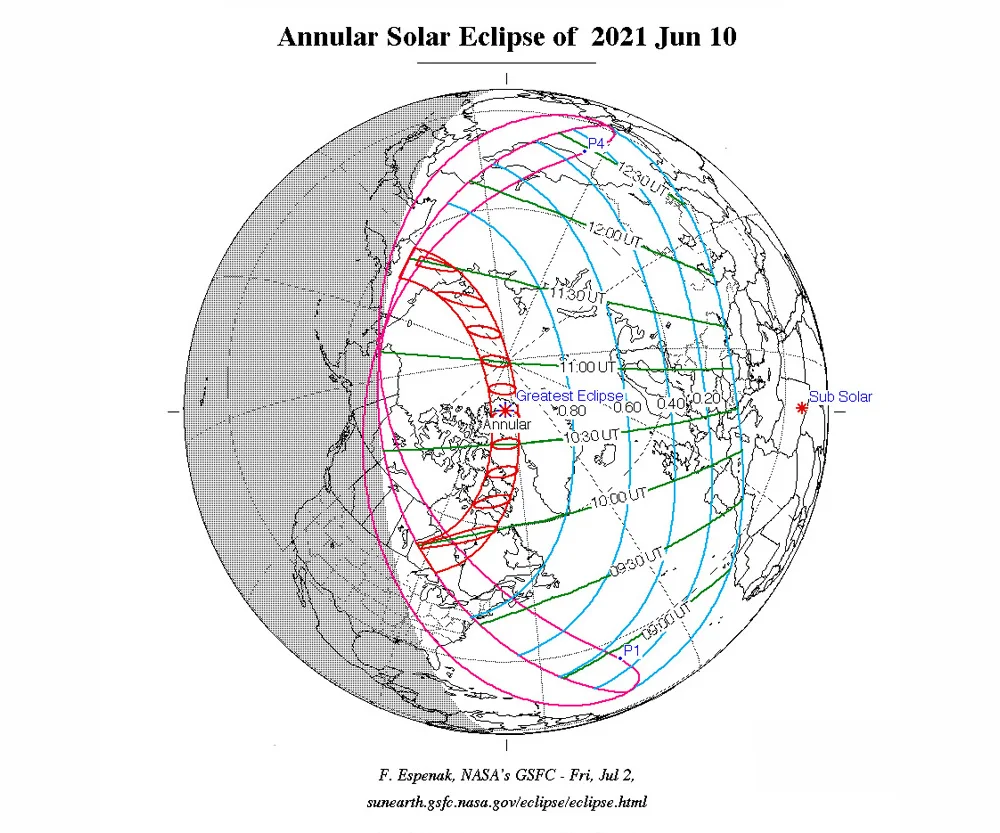

One of the season's last events will be the June 10 Annular Solar Eclipse. Visible across parts of northern Canada and the Arctic, an annular eclipse is also known as a Ring of Fire solar eclipse.

The annular solar eclipse of 2012. Credit: Nakae/Wikimedia Commons

An annular solar eclipse looks so different from a total solar eclipse due to the Moon's distance and thus its apparent size. As the Moon travels around the Earth, it follows an elliptical orbit. So, sometimes it is closer to Earth, and other times it is farther from Earth. If an eclipse happens when the Moon is closer than usual, it appears large enough to completely cover the Sun's disk. If the Sun, Moon and Earth line up when the Moon is farther away, the Moon doesn't block all of the Sun's light. Instead, it leaves a ring of the Sun's disk around it.

There is a brief safe moment to look at a total solar eclipse without eye protection, right when the Sun is completely covered by the Moon. In contrast, there is no safe time to do so during an annular eclipse.

The path of the annular solar eclipses of June 2021. Credit: Fred Espenak/NASA GSFC

Since this eclipse's path follows such an unusual (and extreme northerly) path, it is not an ideal one to get out to see for yourself. There may be live streams set up to view this one online, though.

TIPS FOR METEOR WATCHING

First, some honest truth: Many people who want to watch a meteor shower end up missing out on the experience. Follow this guide to get the most out of these events.

Here are the three 'best practices' for watching meteor showers:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Clear skies are very important for meteor-spotting. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin an attempt to see a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. If you look up into the sky, are the only bright lights you see street lights or signs, the Moon, maybe a planet or two, and passing airliners? If so, your sky is just not dark enough for you to see any meteors. You might catch a bright fireball, but there's no guarantee, and those are typically few and far between. So, get out of the city, and the farther away you can get, the better!

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village until a multitude of stars is visible above your head. In some areas, especially southwestern and central Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over.

In these areas of concentrated light pollution, there are dark sky preserves. However, a skywatcher's best bet for dark skies is usually to drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

Sometimes, based on the timing, the Moon is also a source of light pollution, and it can wash out all but the brightest meteors. We can't get away from the Moon, so we can just make do as best we can in these situations.

Once you've verified you have clear skies, and you've gotten away from light pollution, this is where having patience comes in.

For best viewing, you must give your eyes time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but the longer, the better. Warning: if you skip this step — even if you follow the rest of this guide — you will miss out on a lot of the action.

During this adjustment time, avoid all bright light sources - overhead lights, car headlights and interior lights, and cellphone and tablet screens. Any exposure to bright light during this period will cancel out some or all the progress you've made, forcing you to start over. Shield your eyes from light sources. If you need to use your cellphone during this time, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off and reduce the screen's brightness as much as possible. It may also be worth finding an app that puts your phone into 'night mode' to shift the screen colours into the red end of the light spectrum, which has less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly look up into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark. If the Moon is shining brightly, turn so that it is out of your personal field of view.

Once you're all set, just look straight up!