Zoozve, the 'quasi-moon' of Venus, turns space art error into cosmic reality

The bizarre story of how an illustrator, a podcaster, and an astronomer etched a space art mistake onto the heavens.

Sometimes, artistic impressions of our solar system contain whimsical or difficult-to-explain oddities. In one case, though, the accidental inclusion of a moon of Venus in a space poster was accurate enough that this authentic object — 'Zoozve' — has now been officially named by the International Astronomical Union.

Ask any astronomer or planetary scientist. Look it up in any science textbook or reference book to our solar system. Check with any online source of facts about space. They will all agree that Venus, the second planet from our Sun, has no moons.

Venus has no moons. Credit: NASA

So, Latif Nasser, a co-host of the radio show and podcast Radiolab, was understandably a little confused when he looked closely at a space art poster hanging above his young son's crib.

According to the poster, which was the work of UK artist Alex Foster, Venus had a tiny companion. It was apparently named Zoozve.

As Nasser explained in a thread on X (formerly Twitter), this led him on a journey of discovery with some fantastic results.

Credits: Latif Nasser/Alex Foster

Internet searches confirmed Venus' moonless status but failed to reveal anything concrete about a space object named Zoozve.

A call to his friend Liz Landau, who has extensive experience in the space and astronomy community and is currently the Senior Communications Specialist at NASA Headquarters, was also fruitless. She had never heard of Zoozve before.

"This started to bug me: why make up a moon on a kids' poster?" Nasser said. "And why call it Zoozve?! (Best guess: it was a prank and Zoozve was the illustrator's dog's name.)."

It wasn't long, though, before Landau called Nasser back. Instead of the name starting with ZOOZ, she suggested that it was actually 2002. When she looked up 2002 VE, that delivered a solid result.

Discovered on November 11, 2002, the object designated as 2002 VE68 is an asteroid roughly 230 metres across, or about half the height of the CN Tower. And while it isn't technically a moon of Venus, it also kind of is.

"It's not a moon of Venus, but it's also not not a moon of Venus," Nasser explained to co-host Lulu Miller during their January 26 Radiolab episode. "Because 2002 VE, which I'm just going to keep calling Zoozve, is a mischievous, weirdo character that defies long-held rules of our solar system and upends, at least for me, the way I think about the entire universe."

You see, 2002 VE68 is a special kind of solar system object known as a quasi-moon.

Astronomers have catalogued 10 or so quasi-moons, most of which 'belong' to Earth. 2002 VE68, though, is a quasi-moon of Venus and the very first quasi-moon ever discovered.

Moon vs Quasi-Moon

Scientific definitions govern what is a moon and what isn't. However, the easiest way to tell the difference between a moon and a quasi-moon is to watch how they move through the cosmos.

A moon will trace out a smooth, elliptical path around its planet. However, its path around the Sun will be far more complex, forming a spirograph that oscillates back and forth across its planet's orbital path.

The Moon may trace a smooth elliptical orbit around Earth (top right), but if you look at the Moon's path with respect to the Sun (left) it looks like a spirograph as it oscillates back and forth across Earth's orbit. Credits: Moon's path around the Sun c/o Geologician/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0 DEED), Moon's orbit around Earth courtesy NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio

In contrast, a quasi-moon follows a smooth, elliptical path around the Sun. At the same time, though, its orbit is so closely synced up with a planet that it also appears to have a strangely shaped orbit around that planet.

In the animation above, plotted by Western University astronomer Paul Wiegert, Venus' orbit is shown in green. In grey, the orbit of 2022 VE68 follows a perfect ellipse around the Sun. However, from the perspective of someone standing on Venus, it would appear that the asteroid has a bean-shaped orbit around the planet.

A quasi-moon does this because of gravity.

While the Sun is the primary focus of 2002 VE68's orbit, it has received enough gravitational tugs and nudges from Venus to settle into a 'resonance' orbit with the planet. Basically, despite the very different shapes of their orbits, they take almost exactly the same amount of time to travel around the Sun. Due to this cosmic combination, the result is that the asteroid appears as though it is orbiting both the Sun and Venus at the same time.

Venus and 2002 VE68 do not stray too far from one another as they travel around the Sun. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Scott Sutherland

Unfortunately, this is not meant to last.

According to research, 2002 VE68 has only been a quasi-moon of Venus for about 7,000 years. Before that, it may have simply been a near-Earth asteroid, and our planet's gravity flung it over into its current resonance with Venus.

However, in another 500 years or so, the chaotic interaction between the Sun, Venus, and 2002 VE68 is expected to eject the asteroid from its quasi-moon status.

"Zoozve is following rules that we can never fully grasp," Nasser said. "It presents a mathematical conundrum known as the three-body problem."

"The three-body problem is this idea that if you're mathematically trying to predict and understand these two bodies that are orbiting one another, like the Earth and the Moon or the Sun and the Earth, that's totally doable," he explained. "When you literally add one other thing — when there's three bodies — all of a sudden the math becomes exponentially more difficult. So, you cannot calculate where Zoozve is going to go next."

Who names an asteroid?

When astronomers first spot a new object in the sky, it gets a provisional 'starter' name that begins with the year the object was first spotted, followed by at least two upper-case letters to denote which part of the year it was found.

The first letter is A through Y for the half-month of its discovery (skipping 'I' and 'Z' to give 24 letters). The second letter, A through Z (skipping 'I' again), accounts for the order in which the object was found during that half-month.

However, since thousands of objects can be discovered at a time, astronomers added subscript numbers at the end of the name. Once they reach the 26th discovery, they flip back to A and add a subscript 1. The 51st discovery gets an A with a subscript 2, the 101st discovery has a subscript 3, and so on. For example, asteroid 2015 BH568, discovered in the second half of January 2015, was the 14,208th object found in that half-month.

The different parts of an asteroid's provisional name and what they mean. Credit: Scott Sutherland. Background image courtesy NASA

With the provisional name 2002 VE68, Venus' odd quasi-moon was the 1,705th asteroid discovered in the first half of November 2002.

This system works well for cataloguing large numbers of objects, giving an astronomer key information about the asteroid just by glancing at its name. It's a bit clunky when these celestial objects make the news, though.

Fortunately, once an asteroid has been studied sufficiently, the astronomer who found it can request an official final name.

Approving that name falls to a group of astronomers from around the world working with the International Astronomical Union (IAU). They go by the equally clunky name of Working Group Small Bodies Nomenclature.

The 11 voting members of the WGSBN follow a specific set of rules: the name can be up to 16 characters long, preferably one word, pronounceable in some language, non-offensive, and not too similar to any existing name of a Minor Planet or natural Planetary satellite. Plus, naming an object after a pet is discouraged, and they won't accept names of a commercial nature. There are also specific types of objects that must receive mythical names.

Turning an error into a cosmic reality

So, Alex Foster is the first to admit that including Zoozve in his space art poster was an error.

When Foster found 2002 VE68 on some list identifying it as a moon of Venus, he likely wrote it down, possibly omitting the subscript number. (He cannot recall the list, and Nasser could not locate it.) Since he prints in block letters, when he returned to his note later, he misread it as ZOOZVE.

As he told The Weather Network in an email, "this isn't an area of expertise for me, just a casual interest."

That's totally fair.

Credit: Alex Foster/Latif Nasser

However, Nasser didn't want the story to end just there. He wanted the space art poster on his 2-year-old son's wall to be correct.

Western University astronomer Paul Wiegert — one of the scientists who studied 2002 VE68's quasi-moon nature — ultimately revealed how that could be accomplished.

When Wiegert told him about 2002 VE68 only being the asteroid's temporary designation, Nasser talked with astronomer Brian Skiff, who officially discovered the asteroid, to see if he'd agree to an ambitious proposal — to ask the IAU to formally name this quasi-moon Zoozve.

Nasser sent his submission to Skiff, which read: "As the first quasi-moon ever discovered in the universe, this object deserves a name as rare as its orbit. When artist Alex Foster drew this solar system object on a poster for kids, he misread the temporary name 2002 VE as Zoozve, thus coining this original, odd, and memorable name."

It was a long shot. This asteroid comes close enough to Earth (to around 6 million kilometres once every 8 years or so) to be designated as a potentially hazardous asteroid. Based on the IAU rules, it could require a mythological name. Regardless, Nasser and Skiff went for it anyway.

They had to wait over three months for the answer, and even as of the January 26 Radiolab episode where Nasser discussed his adventure in asteroid naming, there still had not been a definitive response from the IAU group.

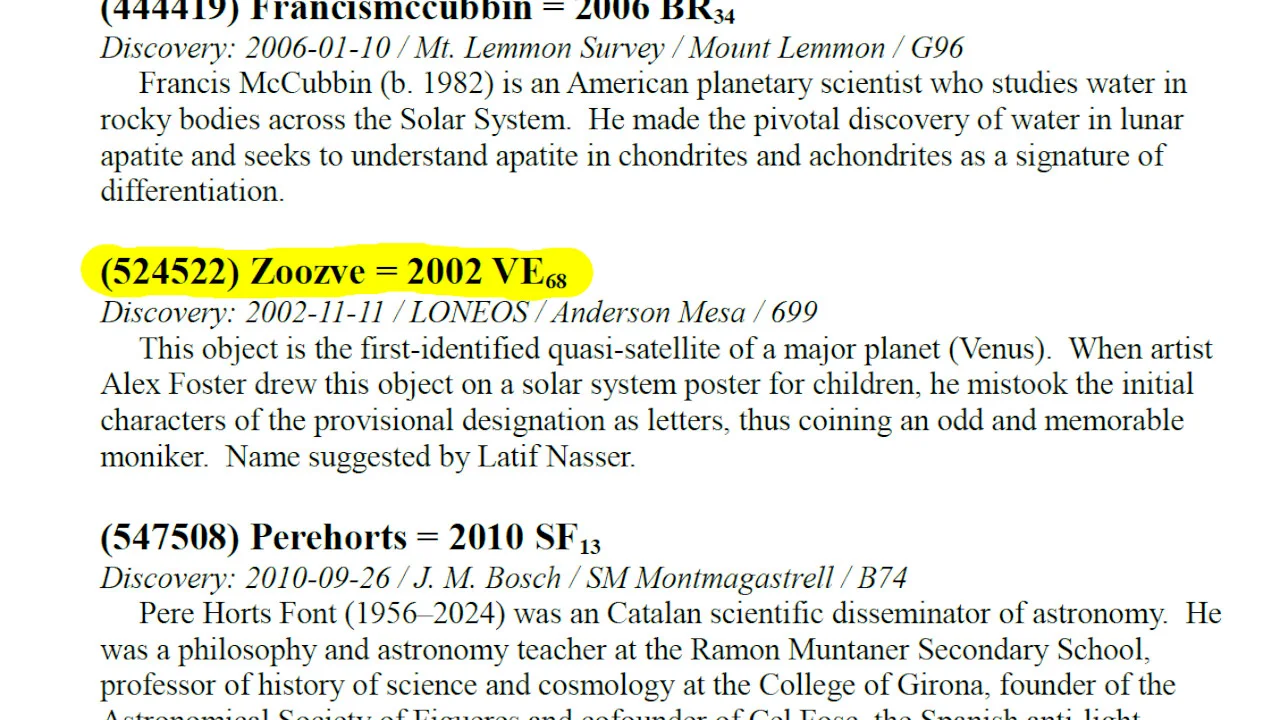

However, as of the February 5, 2024 WGSBN Bulletin, their long shot paid off!

Credit: IAU

2002 VE68 has now been officially named Zoozve! The (524522) denotes that it is the 524,522nd entry in the IAU's 'minor planets' catalogue.

In an update on the Radiolab site from that same day, Nasser shared the news with co-host Lulu Miller!

"Your mistake is now etched in the heavens forever," Nasser told Foster in a telephone call. "That retroactively makes the poster correct!"

For Foster, the entire experience has been surreal.

"I feel like I haven't really slowed down much to think about the whole thing," Foster said via email, "but it's a bit surreal and strange to think how it's all turned out — all starting with making an error years ago when I made the print."

The response to Zoozve has been big, with hundreds of new orders coming in for Foster's Solar System print via his online store. As for any potential new space art showing up on his site, Foster says he has plenty of new ideas for when he has the time.

"Maybe something like a Quasi Moon print with some info, or some sort of Zoozve poster," he said. "There's also fun and silly ideas inspired by the fan club-like messages I'm getting about Zoozve."

Thumbnail image courtesy Alex Foster and Latif Nasser