Solar max is approaching. Here’s where and how to see the Northern Lights

The next few years could be the opportunity of a lifetime to witness the Aurora Borealis. Don’t miss out!

This vibrant display of the Northern Lights was captured from Ethel Lake, Yukon, on September 3, 2022. A curtain of bright green pillars is visible most prominently along the ‘front’ of the display, with a more diffuse patch of green beyond it. Above the pillars, a faint mixture of red, purple and blue light is visible. Credit: Susan Pearse/UGC

Solar activity is ramping up fast and with that will come our best chances to see the Northern Lights. But what causes these amazing displays and where can we go to improve our odds of viewing them?

The Aurora Borealis, aka the Northern Lights, has captivated people for millennia. These ethereal displays of light in the night sky appear as if spawned by magic. It’s really no wonder why northern cultures feature it prominently in their mythology as a supernatural link to realms beyond our world.

These days, we understand the science behind the phenomenon. However, even with that knowledge, the auroras still spark an incredible sense of awe and wonder. Witnessing one of these displays can be a life-altering experience, and people travel thousands of kilometres just to see them.

What are the auroras?

The Aurora Borealis, along with its southern counterpart, the Aurora Australis, are displays of coloured light that shine across the night sky.

They vary in intensity, sometimes so faint you can barely see them, while at other times they can shine so brightly you can read by their light alone. Auroras can appear for just an instant or shine for hours at a time, lighting up the entire night. In some cases, especially for regions close to the poles, auroras can even persist for days, fading from sight at daybreak and then returning once the Sun has set.

Auroras take on many different shapes, as well. They can appear as ribbons, arcs, or curtains stretching from horizon to horizon. They can show up as diffuse patches or swirls of colour. Some displays also include pillars, rays, or bands, and when shining overhead, they can appear as spectacular coronas.

Courtesy of Yukon Tourism, Northern Lights Resort & Spa

The most common colour for the auroras is green. However, they can also display shades of red, blue, and purple. In rare instances, pink, yellow, and even orange auroras can also appear.

Mostly, auroras are a polar phenomenon, as they are often seen only from the farthest northern and southern regions of Earth. At times, though, they can extend far away from the poles, becoming visible to millions of people as they shine overhead.

Right now, through the end of 2023 and the first half of 2024, we are nearing a period of time known as ‘solar maximum’. Aurora displays are already becoming more frequent and more intense. As we draw closer to solar max, this trend will continue, giving us more opportunities to witness this awe-inspiring natural wonder.

Where do the auroras come from?

Every display of the Northern or Southern Lights, regardless of the location, shape, or colour of the auroras, results from the same process.

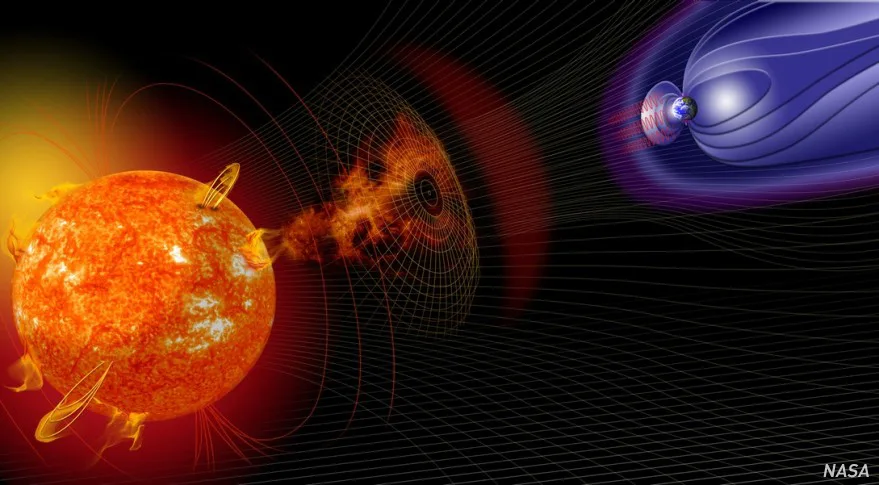

This artist’s impression reveals the various ways in which solar activity can affect the Earth, which is collectively known as ‘space weather’. Credit: NASA

It all begins at the centre of our solar system. Even during its most quiet periods, the Sun emits a constant flow of high-energy particles into space that we call the solar wind. Just like the wind here on Earth, at times the solar wind flows slowly, while at other times it is considerably more blustery.

As the solar wind flows past Earth, the planet’s magnetic field captures some of the particles from the stream and funnels them down into the upper atmosphere near the poles. There, they collide with oxygen, nitrogen, and other gasses in the atmosphere, energizing them and causing them to emit flashes of coloured light.

Ribbons of the Northern Lights stretched across the sky above Whitehorse, YT, on August 31, 2012. Credit: David Cartier Sr/NASA Goddard

Green auroras are produced by oxygen molecules between 100 and 300 kilometres above the ground. Red auroras are the result of collisions with free atoms of oxygen at altitudes of 300 to 400 km. Pink or dark red seen along the lower edge of green auroras are due to nitrogen molecules being impacted during particularly strong episodes of aurora activity. Nitrogen can also produce blue auroras higher up, which, combined with red from atomic oxygen, often shows up as purple. Blue and purple auroras have also been attributed to hydrogen and helium atoms impacted during these events.

Even when solar activity is at its minimum, leaving only the solar wind to affect us, we still see auroras wrapping around the north and south poles on a fairly regular basis.

However, the most intense and widespread auroras tend to occur when solar activity is at its greatest.

Our active Sun

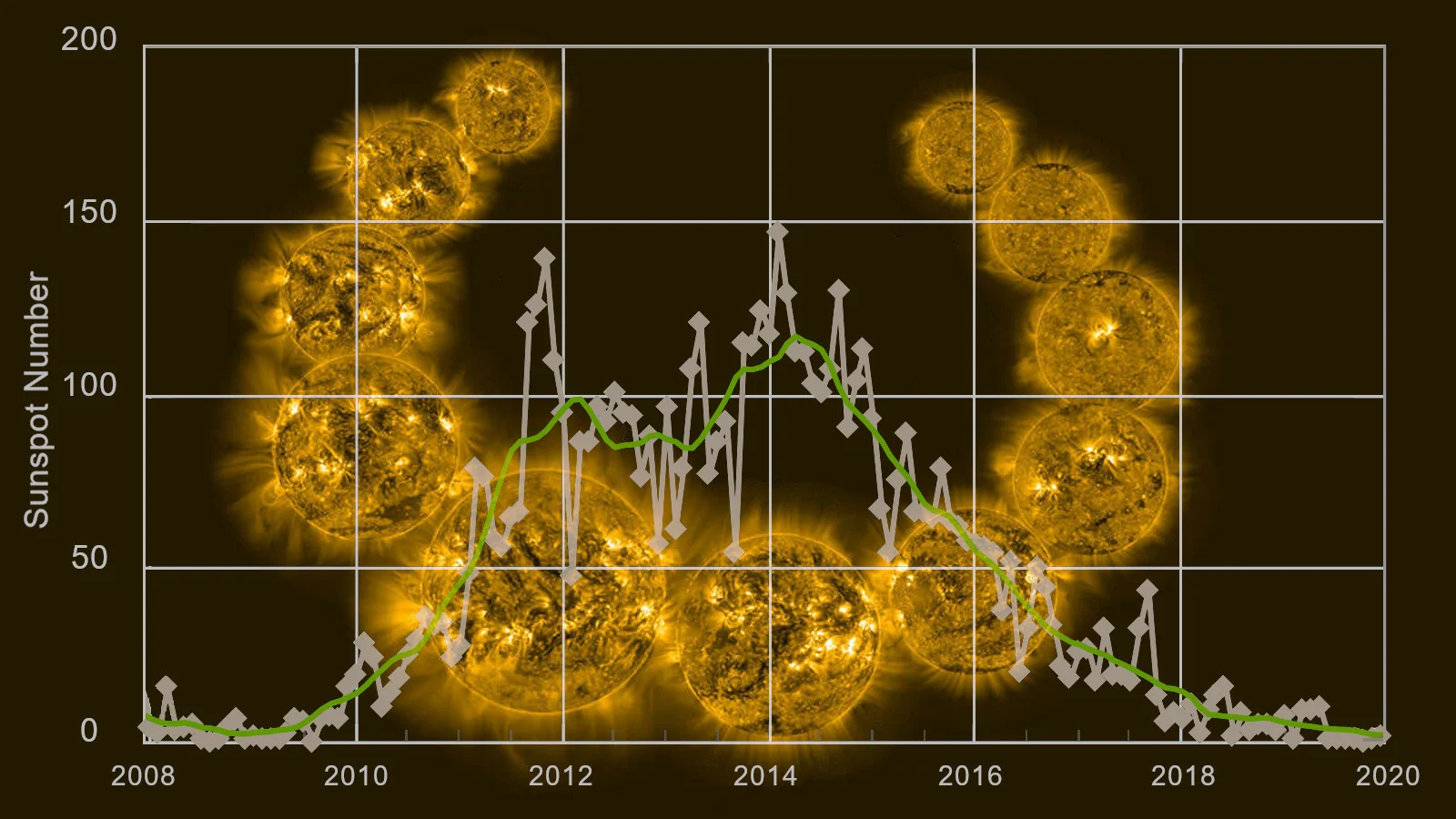

The progression of Solar Cycle 24, from 2008 through 2019, is shown in this graph of sunspot count, revealing how their numbers increased through the first half of the cycle, reached a double peak between 2011 and 2014, and then diminished back to a minimum. In the background, eleven different views of the Sun are presented throughout the cycle, taken by the SWAP extreme UV imager on Europe's PROBA2 satellite. Credits: graph from NOAA SWPC, background image courtesy Dan Seaton/European Space Agency/NOAA/JPL-Caltech

The solar wind is the most constant form of 'space weather' produced by the Sun. However, as an active star, the Sun also goes through cycles of activity, each roughly 11 years long and following a similar pattern. At the beginning, solar activity starts out relatively quiet. Over the next 5-6 years activity ramps up to a peak, with more sunspots, and increasingly frequent and more intense solar flares. After that, while we can still see some fairly intense events throughout the second half of the cycle, the overall frequency and intensity of activity gradually decreases to a minimum again.

Each solar cycle is unique, though. Solar Cycle 24, which ran from 2008 to 2019, was the weakest seen since the 1800s. The current cycle, Solar Cycle 25, was initially forecast to reach a similar or even weaker maximum in 2025. However, activity so far has already surpassed that forecast and NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center says the cycle will likely peak in 2024 — a year early and significantly stronger than originally expected. That means there will likely be more and increasingly intense solar activity in the months ahead.

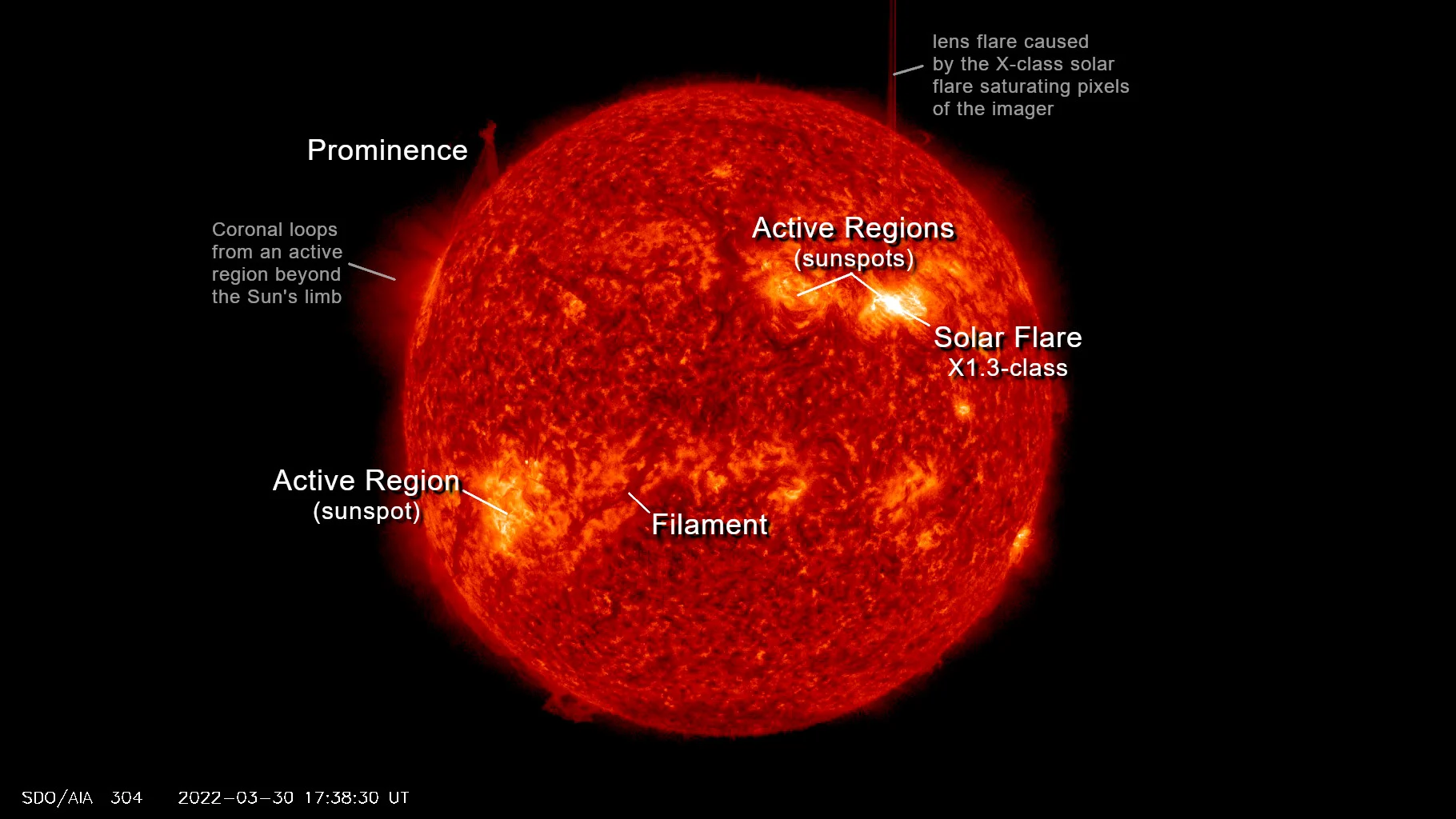

This image of the Sun in extreme ultraviolet light was taken by the Solar Dynamics Observatory on March 30, 2022. Several examples of solar activity are labelled, including a powerful solar flare that exploded on that day. Credit: Scott Sutherland/NASA SDO

The most obvious signs of increased solar activity are sunspots and solar flares. Sunspots are cooler, darker regions of the Sun's surface that are exposed to space by tangled up magnetic fields. When those tangles suddenly unravel, it causes an intense burst of energy, UV light, and X-rays that we call a solar flare. Typically, the more severe the tangles, the more intense the resulting flare.

The type of solar activity most associated with auroras, though, is the coronal mass ejection. In the wake of a solar flare, an immense cloud of solar plasma can erupt into space from the same region of the Sun. These 'solar storms' then expand outward, sweeping through interplanetary space while carrying some of the flare's energy along with it.

This immense coronal mass ejection (CME) erupted from the Sun on August 31, 2012, and was captured in great detail by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. A graphic of Earth has been added to the image to properly scale this monster eruption. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

When one of these CMEs sweeps past Earth, the sharp increase in high-energy particles streaming by the planet can result in a disturbance in Earth’s magnetic field known as a geomagnetic storm.

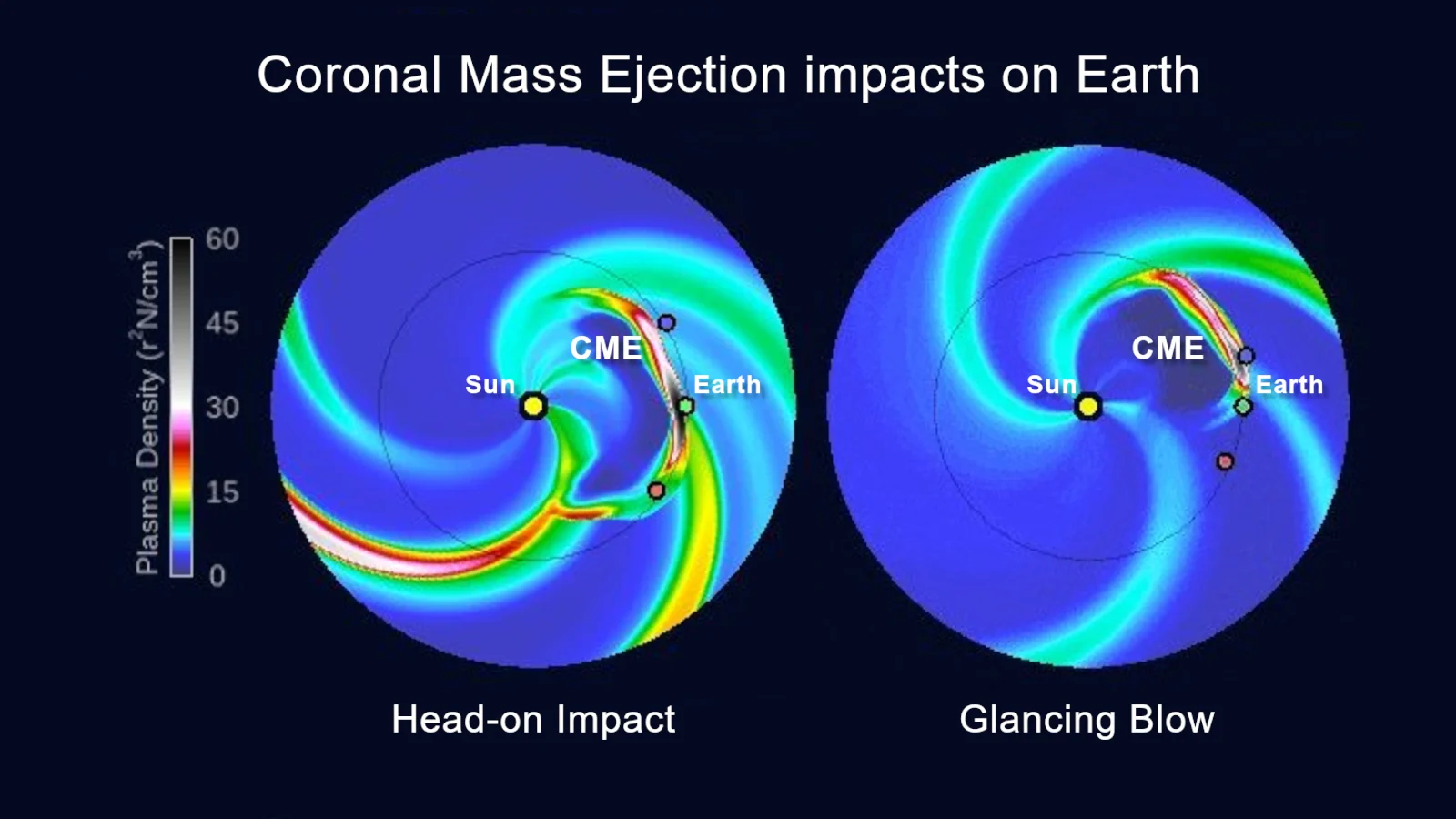

The strength of the geomagnetic storm largely depends on the density and energy of the CME, but also on what kind of impact it has on Earth — whether it is a head-on impact or a glancing blow.

These two simulations show two different coronal mass ejections passing by Earth (green dot), the first making a direct hit with the densest part of the solar storm (left), and the second scoring a glancing blow, where only the very edge of the CME interacts with Earth’s magnetic field (right). The pinwheel pattern around the Sun represents the solar wind — dark blue for faster, diffuse streams, and shades of green through red and white for slower, denser flows. The red and blue dots in each example represent NASA’s twin STEREO spacecraft, which monitor solar activity. Credit: NOAA SWPC/Scott Sutherland

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center ranks geomagnetic storms on a scale of G1 (minor) through G5 (extreme). Each level on the scale causes brighter and more widespread aurora displays. Along with that, each higher level also includes a greater potential for problems with satellites, spacecraft in orbit, and power grids on the ground.

A minor impact from a CME, such as from a glancing blow, can result in bright auroras visible from southern British Columbia, the southern Prairies, northern Ontario, central Quebec, and the northern parts of Atlantic Canada. A major impact, either from a more direct hit or due to a larger and more energetic CME, ramps up the aurora brightness and can push the auroral arc south of the Great Lakes and over the central United States. There have also been rare instances, the most famous occurring more than a century ago, where auroras could even be spotted from the tropics.

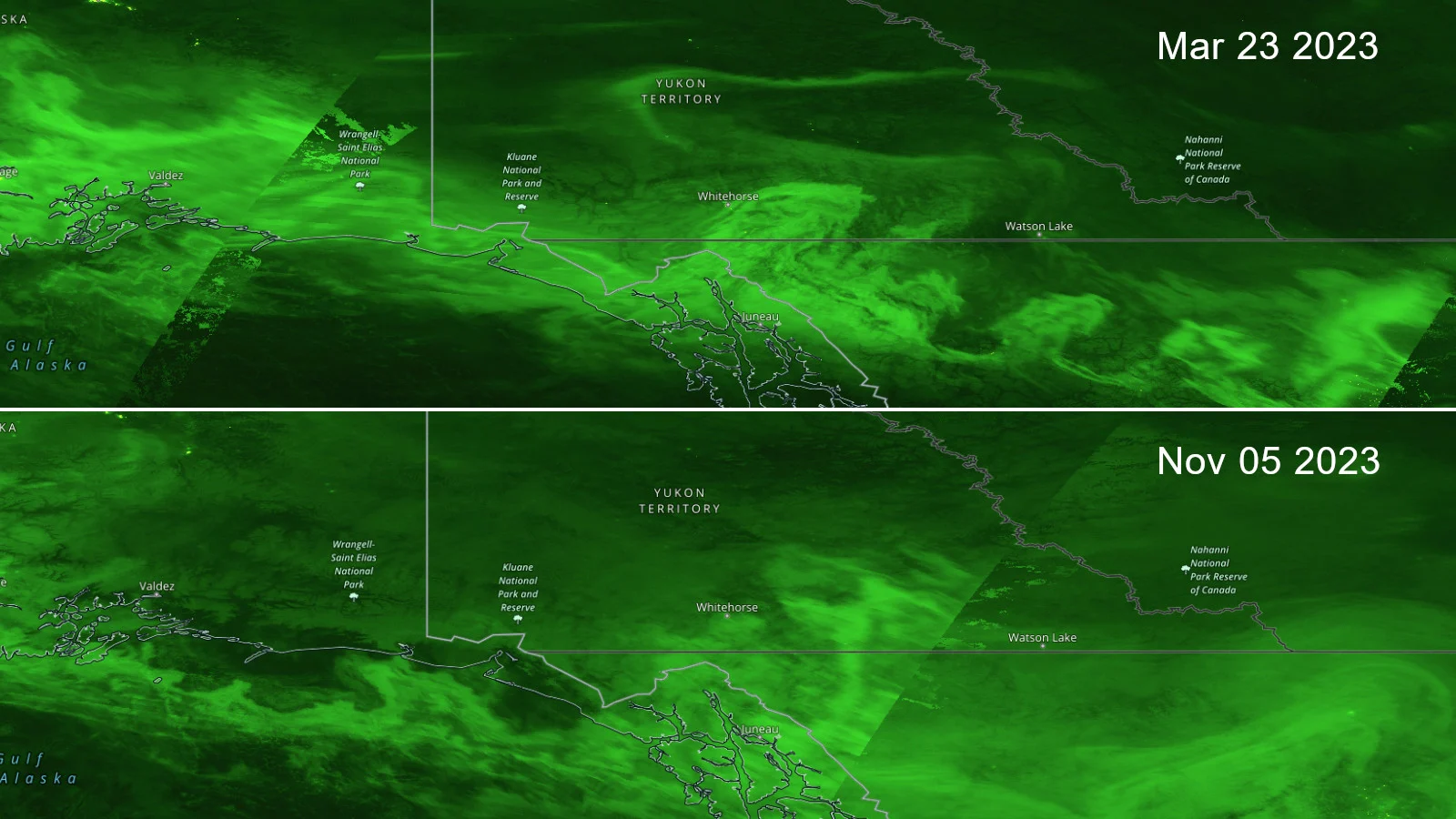

Most recently, on the night of November 5, 2023, a passing CME sparked auroras that were visible across wide areas of Europe, Canada, and the United States. This event registered as a G3 (strong) geomagnetic storm on NOAA’s scale.

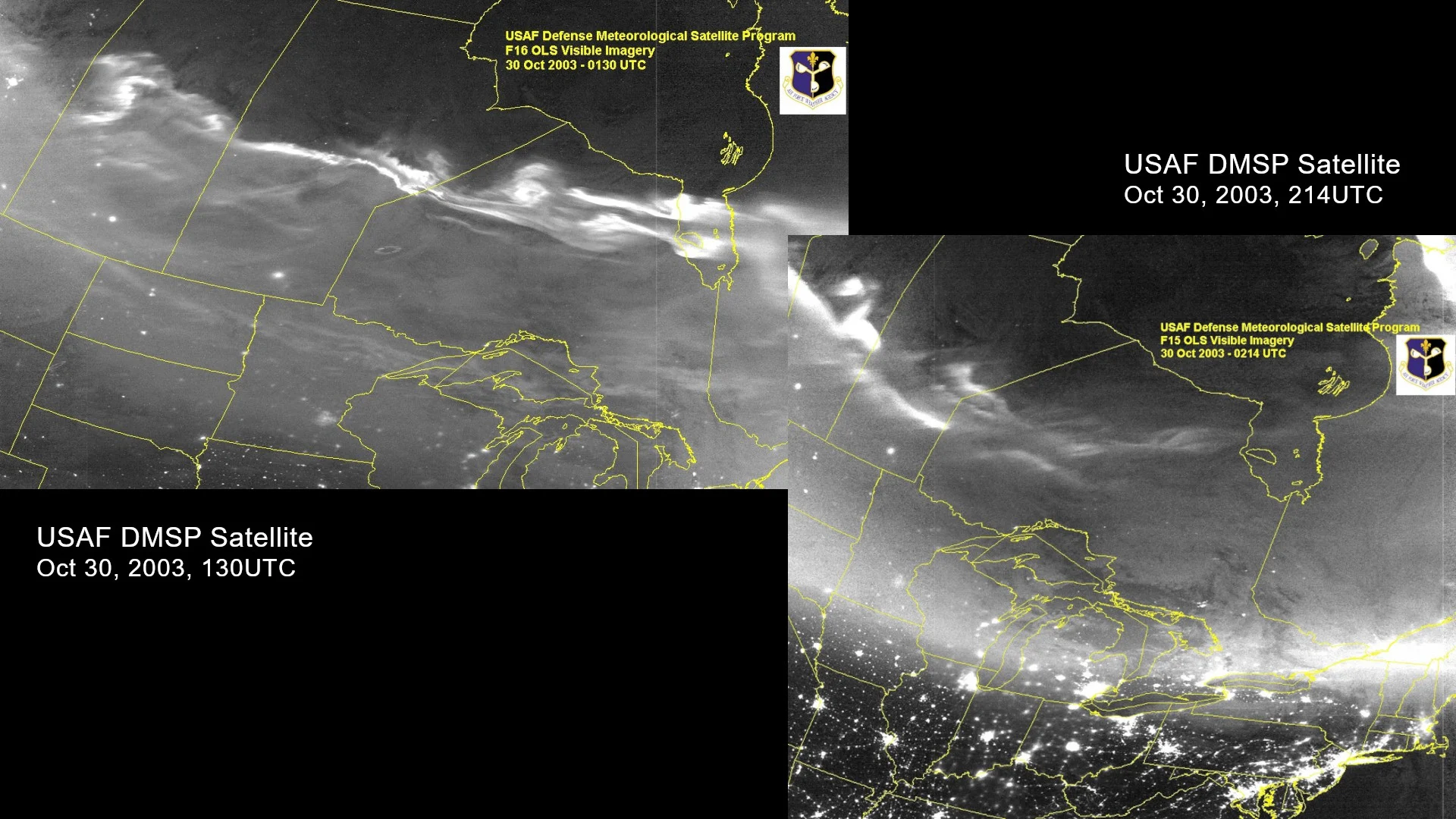

The strongest event seen in modern times — a G5 (extreme) geomagnetic storm — occurred roughly 20 years ago, during the Halloween Solar Storms of 2003. According to NOAA, “Aurora sightings occurred from California to Texas to Florida. People in Australia, central Europe, and even as far south as the Mediterranean countries also reported tremendous aurora viewing.”

These two images taken by the US Air Force’s F15 DMSP satellite on the night of October 29-30, 2003 reveal aurora activity on that night, represented by the bright hazy areas of the map. The northern extent of the auroral arc was across northern Ontario and the central Prairies and they extended south across the Great Lakes and into the northern United States. Credit: Meteorological Satellite Applications Branch, AF Weather Agency/spaceweather.com

With Solar Cycle 23 having peaked in 2000, the timing of this event reveals that intense solar activity does not end once solar maximum has been reached. Indeed, we can still see some amazing events in the few years immediately following the peak of a solar cycle.

Where to see the auroras for Solar Max 25?

Over the next few years, there are likely to be several instances where the Northern Lights extend down over much of Canada and the northern United States. We may even see an event or two in which they become even more widespread. However, it’s not easy to predict these events far in advance.

Space weather scientists can typically give us a few weeks' notice of potential auroras due to a strong flow of the solar wind, and perhaps 3 days warning, at most, for the arrival of a solar storm. Even when these impacts occur as expected, though, the exact conditions may not be right to spark auroras that become visible far to the south.

So, perhaps the best way to maximize your chances of seeing auroras in the months leading up to solar maximum is to head north.

In particular, Whitehorse, Yukon, can experience some spectacular displays of the Northern Lights. The phenomenon has even become one of the most popular reasons to visit that region of the country.

These two images were captured on March 23, 2023 (top) and November 5, 2023 (bottom) by the polar-orbiting Suomi NPP weather satellite. Auroras, shown in green, were widespread over northern regions of Canada on those nights, with the most intense part of the aurora oval passing directly over or within sight of Whitehorse, Yukon. Credit: NOAA/NASA

The best time of year to see the auroras from there, according to Yukon Tourism, is typically from August through April. Indeed, looking at 2023 so far, counting all nights from January through April, auroras shone in the sky over Whitehorse a little over half the time. Since the end of August, they have been visible in some form, including some very intense displays, during more than three-quarters of all nights.

Over the next four to five months, though, auroras will likely occur even more frequently.

Additionally, the best time to watch the Northern Lights may be through the middle of the night (usually between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m.). However, the 13-15 hours of darkness experienced each night in southern Yukon over the months ahead will provide significantly more potential aurora viewing time than locations farther south.

Although the location may be remote, you wouldn’t necessarily be on your own. According to the Yukon Tourism website, there are several ways to experience the auroras from the area. Local operators conduct nightly tours, while wilderness lodge and cabin experiences offer a way to view them on your own schedule. They even recommend Dawson City’s Midnight Dome as an excellent place from which to view the Northern Lights.

Expect the unexpected

This solar cycle is developing faster than anticipated. Experts believe that as we approach next year’s solar maximum, we could see the best aurora displays of the past 20 years. They could also exceed anything that’s to come for the decade following solar maximum, as well.

It’s interesting to note, however, that this unexpectedly strong solar cycle could have even more surprises in store for us. So, keep an eye on the skies in the year ahead.

(Thumbnail image courtesy Susan Pearse, who captured this display of the Northern Lights above Ethel Lake, Yukon, on September 3, 2022, and uploaded it into the Weather Network UGC Gallery)