What N.W.T.'s Smoking Hills could tell us about Mars

The sea cliffs of Franklin Bay with active burning shale send clouds of smoke inland. (Submitted by Natural Resources Canada)

On smoldering earth so hot it will melt your boots, researchers say they have found jarosite formations, which are plentiful on Mars, but far less common on Earth.

The Smoking Hills, an Arctic coastal area between Tuktoyaktuk and Paulatuk, N.W.T., that is known as Ingniryuat in Inuvialuit, are offering scientists an opportunity to learn how the mineral formed on the red planet.

"You don't see burning rocks all over the world," said Steve Grasby, a scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, part of Natural Resources Canada, who recently published research in the journal Chemical Geology.

Canadian scientists have gathered samples from the Smoking Hills, which sit at the mouth of the Horton River, where it meets the Beaufort Sea. The area is highly acidic and has jarosite layered in low-grade shales that were deposited in the ocean about 83 million years ago.

Grasby and his fellow researchers say the Northwest Territories' Smoking Hills area could be used to study Martian jarosite.

The Opportunity rover during the exploration of Meridiani Planum on Mars, where jarosite on the planet was first discovered. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU)

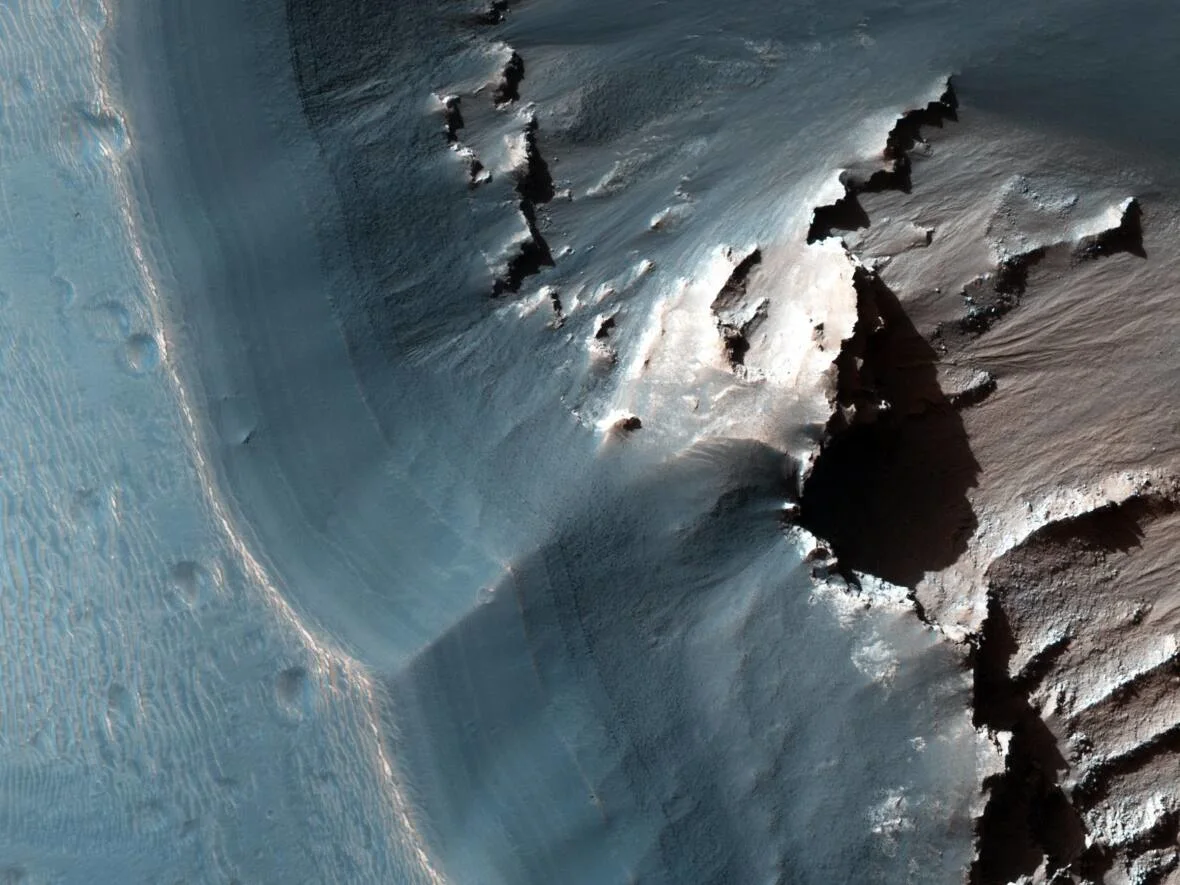

A 2015 image capture by a high resolution camera aboard the NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the eastern Noctis Labyrinthus region of Mars, confirming that jarosite is a common mineral on the plant. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona)

Jarosite is common on Mars. It was first identified by the Opportunity Rover, and then by other rovers on the planet, and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

NASA states that the images and data collected from Mars could indicate volcanic, acidic and aqueous conditions.

Scientists working with data from NASA's Mars research program would like to work with the same instruments they use on Mars to gather data on the earthly formations, said Grasby.

Future research of the area, Grasby said, is to be discussed in consultation with community members in Paulatuk and Tuktoyaktuk, the communities near the Smoking Hills.

The Smoking Hills area is the subject of northern lore, as told in this 2018 edition of Tusaayaksat Magazine with stories of spirits hiding in the hills and minerals used to cure sick dogs.

Research Scientist Steve Grasby and student assistant Rebecca Bryant collected waters from the toxic acid ponds behind them. (Submitted by Natural Resources Canada)

Ingniryuat doesn't just hold promise for planetary research — the smoldering ground could be of interest to biologists and climate scientists, as well, said Grasby.

The actively burning areas called boccanes are rich with low-grade pyrite shales that automatically combust. Those shales are becoming further exposed by slumping permafrost, said Grasby.

The burning releases clouds of smoke along the whole coastline, he said.

Pyrite is a sulfate that is not stable and when exposed to oxygen becomes jarosite and produces sulfuric acid, which is responsible for the eggy fragrances of the Smoking Hills.

The ground is unbearably hot, said Grasby.

"I have these nice brand new hiking boots that were like expensive leather boots and they're just destroyed. After two weeks of working there, I just had to throw them out," he said.

'EVERYTHING SAYS RUN'

Samples taken by the scientists were so acidic that they have a negative pH, and you need protective clothing and respirators with special filter cartridges to cut out the fumes.

The area is more acidic than a mine tailings drainage site, where jarosite is also found.

"It was difficult to even collect samples," he said.

The rocks and minerals were so hot they melted right through the jars and if spilled, would burn through clothing.

"Everything says run," Grasby laughs.

Ingniryuat (Smoking Hills) is a place known to Inuvialuit communities nearby. (Submitted by Natural Resources Canada)

The surrounding area is more bearable and even beautiful, with rolling open tundra. Depending on the wind direction, it could smell like fresh Arctic air or sulphur dioxide.

"In some areas where the shales have been burning … it turns it all into a red color, so some very vibrant colors to the landscape."

The burning has even changed the course of a river, visible from satelite imagery hosted on Logan Earth.

A satelite map from Logan Earth shows where the Horton River meets the Beaufort Sea. The burning shales have such influence that the river formed a new terminus. 'That’s the new delta forming,' said Grasby. (Logan Earth)

LIFE IN ACIDIC PONDS

Despite this environment — "probably the most acidic natural waters ever reported," said Grasby — life in the Smoking Hills persists.

"In these ponds, there is basically one that's only like one kind of microbes that can handle it and that's pretty rare to have such low diversity."

This life includes algal mats, "extremely simple life" That Grasby and his colleagues at the University of Calgary are also studying.

The microbes that survive there are unique because some of the ways they have adapted to survive acidic environments also make it harder to withstand cold, he said.

A diving beetle found living in the hyper-acidic and toxic ponds of the Smoking Hills. (Submitted by Natural Resources Canada)

Grasby said the rocks in the Ingniryuat were deposited in oceans that were "teeming with life," similar to a modern ocean environment.

The Smoking Hills jarosite formed millions of years after the rocks were deposited, which suggests that even though jarosite was found in presumably acidic places on Mars, Mars may not have always been acidic, said Grasby.

"It could be something that happened millions of years later to form those layers, just like in the Smoking Hills," he said.

HOW LONG HAS THIS BEEN GOING ON?

The smoking shales on Earth appear in other high latitude places, such as Smoky River Alberta, northern Yukon and Greenland.

Researchers want to understand more about when Ingniryuat began to burn, and how extensively the deposits could burn over time.

Ice sheets began melting around 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, but in the N.W.T. study area, it was at least 8,000 years ago that the glaciers receded enough to expose the rocks to oxygen.

Permafrost slumping is speeding up the exposure of these shales, and scientists want to understand how this area could be affected by climate change.

This includes research to measure the extent to which burning river valleys and sea cliffs could be depositing metals like iron, lead, nickel, zinc and arsenic into Arctic waters.

SOLVING A PUZZLE

The scientific community at large has many and diverging theories about rocks found on Mars and their earthly counterparts.

Giovanni Baccolo is an Italian researcher at the University of Milano-Bicocca environmental and earth sciences department. He studies ice cores from Antarctic glaciers to learn about our past climate, environment and planetary history.

Giovanni Baccolo, a researcher at the University of Milano-Bicocca, published a study of Antarctic ice cores that contained jarosite. (Giovanni Baccolo)

Baccolo and his fellow scientists took cores from the Talos Dome in East Antarctica.

Antarctica ice is so "ancient" it dates back hundreds of thousands of years and holds clues for what Earth may have been like during those time periods.

Their hypothesis, published in Nature Communications, is that jarosite is formed by ice weathering.

At 1,000 metres deep, they found jarosite crystals.

A drilling operation at Talos Dome. (TALDICE project)

This surprised Baccolo, who said on Earth, jarosite is found in "very specific" and "peculiar" settings. The environment has to be highly acidic and have some water, but not too much, to form the iron sulphate that is known as Jarosite.

It is found in playas, which are desert environments and volcanic settings with pyrite.

Baccolo said before the Canadian study, scientists hypothesized that jarosite was formed by exposing pyrite to oxygen.

"I've never heard about places like that with the production of such high temperatures because of the degradation of pyrite," he said.

The presence of Jarosite on Mars means that in "in its geologic past there was a lot of water," said Baccolo.

"You can't go there. The only way to study it is to find a good analogue on earth, and so it means you need to find an environment which is as similar as possible to the one you want to study," he said.

He said the presence of jarosite like that studied by Canadian researchers adds to an "exciting" scientific area of study that's searching for explanations to martian jarosite.

"It's a sort of puzzle we are trying to finish but it's difficult," he said.

This article was originally published on CBC.ca, by Reporter Avery Zingel.