Astronomers see unravelling of Jupiter's Great Red Spot

Jupiter's iconic storm is dying.

Over the past week, amateur astronomers around the world have seen some unusual activity around the solar system's largest and longest-lasting storm, known as the Great Red Spot (GRS).

The swirling red clouds that have been raging over the giant planet for centuries have been spotted forming "propellers" along the storm's edges, with these blade-like shapes spinning off and ultimately dissipating.

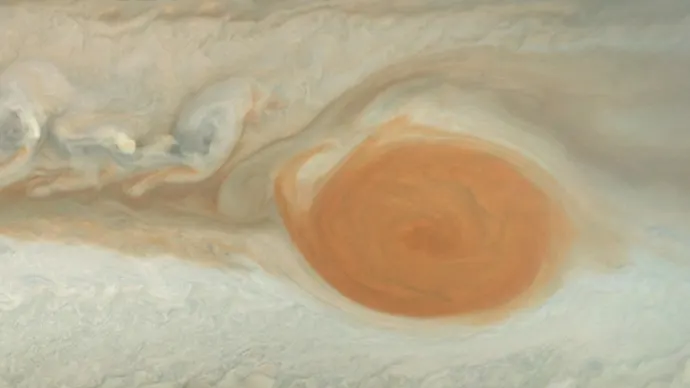

NASA's Juno spacecraft, currently in orbit around Jupiter, captured the Great Red Spot on Feb. 28, 2019. To the storm's left edge, a region of the 400-year-old storm is seen mixing with the surrounding cloud of gases. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Björn Jónsson)

"This is very uncharted territory," said Glenn Orton, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who studies Jupiter. "We've never seen it like this before."

The Great Red Spot is massive - roughly 13,000 kilometres in diameter - and it's been around for at least 400 years. But it has consistently been getting smaller. Decades ago, it could fit three Earths inside it. Now, it's the size of just one Earth.

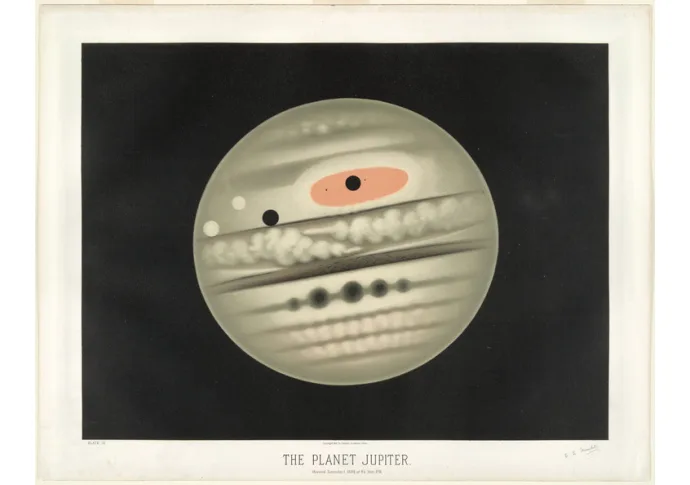

Artist and astronomer Étienne Trouvelot sketched Jupiter and the Great Red Spot in 1880. The storm was clearly much larger then than it is today. (Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library)

Orton said early drawings and images of Jupiter, dating back to the 1870s, showed a storm that looked more like a "great red sausage."

"It's just been shrinking since then," he said. "I've said someday it might become the Great Red Circle. And some [scientists] think that it's not going to be stable, and it'll become the GRM: the Great Red Memory."

In 2017, scientists observed similar activity in the same place, along the western edge of the storm, but "not under the same circumstances," said Orton.

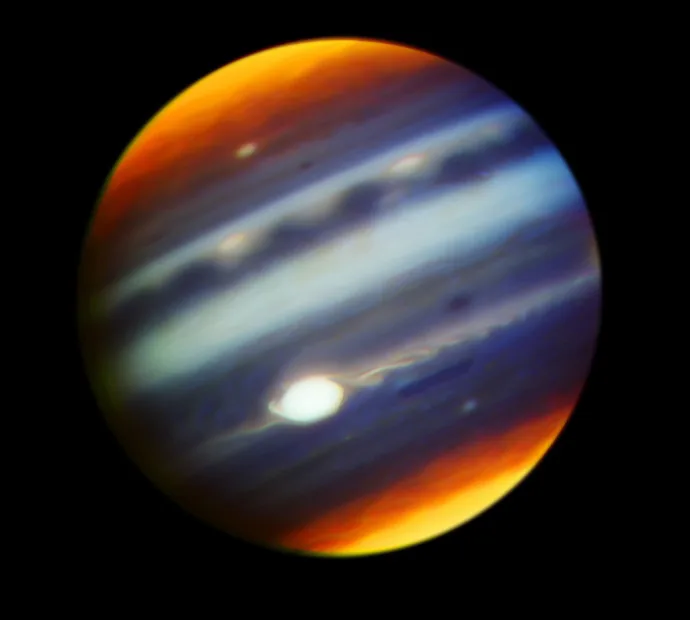

This composite, false-colour infrared image of Jupiter reveals the Great Red Spot's spiral streak that is being stretched out from the storm. (Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/NASA/JPL-Caltech)

What is unusual now, said Orton, is there is this "visibly dark line" going around the planet for the first time.

The space between that band and the oval - or main body - of the storm may be allowing other vortices to come in, which, in turn, pinches off some of the clouds of the GRS.

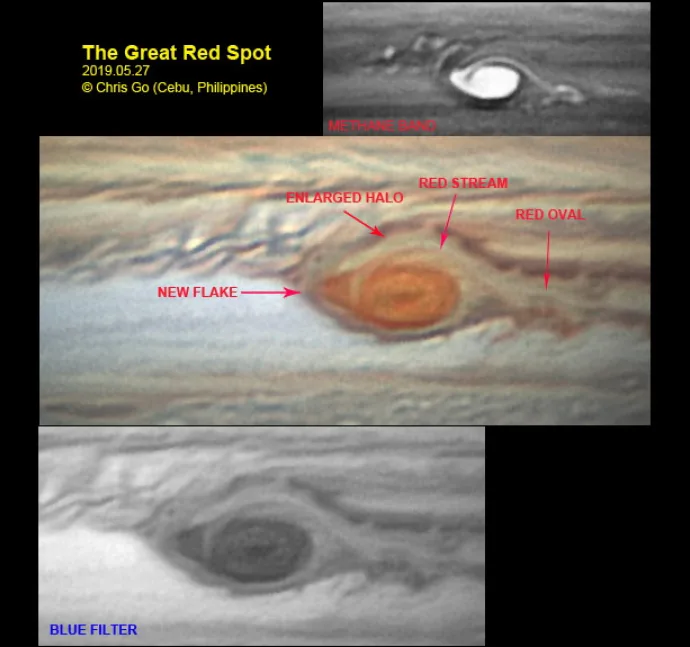

Christopher Go, an amateur astronomer from Cebu City, in the Philippines, captured images of part of the storm on May 26 and 27. Witnessing this type of "unravelling" was a first for Go.

"The oval is ... bleeding material from the GRS," Go said, explaining the process that is transforming the storm. "This material will rotate around the GRS counterclockwise. As it goes south of the GRS, it is expected to distort the GRS, maybe causing it to shrink more."

Amateur astronomer Christopher Go imaged Jupiter's Great Red Spot on May 27. (Submitted by Christopher Go)

Orton said he is very appreciative of such observations by amateur astronomers, like Go, as it helps professional astronomers catch things that might otherwise have gone undetected. Professional astronomers need to book time in advance on the world's large telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, and that time can be precious.

"The amateur community is the one resource that gets measurements of Jupiter," Orton said. "They do the continuous monitoring."

"At any given moment, there is someone, somewhere around the world imaging Jupiter," added Go. "This really helps us in our long-term understanding of Jupiter."

'NOTHING LASTS FOREVER'

Professional astronomers and amateurs alike may get a front-row seat for the action in just a few weeks, when scientists hope to learn more about the massive storm. At the moment, NASA's Juno spacecraft is orbiting Jupiter. It will once again swing over the GRS toward the end of July, Orton said.

"I hope it's still here," he said. "Nothing lasts forever."

Scientists can't say for certain when the Great Red Spot may break apart completely, but Orton said that over the past two weeks, there have been some estimates that the Great Red Spot has already shrunk by five to 15 per cent.

And while his outlook might seem a little gloomy, Orton said he's ready for anything.

"I would have thought that one [propeller] would have come off and that would have been the end of it," he said. "But there was another storm that came by and another shard has come off. So time will tell."

This article was written for the CBC By Senior Science Reporter, Nicole Mortillaro.