Secrets of Canada's seven most famous shipwrecks

Many lives have been lost in Canada's waters over the centuries. These are the stories of seven of those catastrophes.

Storm Dennis, which lashed Europe earlier this month, also had an unexpected side-effect: It washed a cargo ship that had been abandoned since 2018 onto the Irish coast.

The ship had been abandoned after becoming disabled in the Atlantic and its crew evacuated as a hurricane approached, and its path since then has been a mystery, with the idea of a drifting "ghost ship" capturing the popular imagination.

At least it didn't sink and its crew is safe, unlike other cases of shipwrecks. Below is a selection of Canadian shipwrecks that ended in tragedy.

1912: RMS TITANIC

The world’s most famous shipwreck is so well known, it’s almost superfluous to recount what happened. The cursed ship, said to be unsinkable, was on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City in April 1912 when it struck an iceberg, sinking over the course of two hours and 40 minutes.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

The sinking happened around 600 km from the coast of Newfoundland, then a separate dominion. Four Canadian ships set forth to recover any bodies, and 150 of the dead are buried in Halifax.

The sinking was one of the world’s deadliest peacetime catastrophes, with 1,500 people losing their lives, either through drowning or freezing in the frigid North Atlantic.

1805: AENEAS

The British troopship Aeneas, with around 350 people aboard, was part of a convoy sailing to Canada during the Napoleonic Wars, and the harrowing passage across the Atlantic should have been a hint that the voyage was not exactly blessed.

Severe storms slowed the crossing by almost a month, so by the time it reached the waters southwest of Newfoundland, disease and starvation were rife among the passengers crammed into the hold.

Rough seas whipped up by powerful winds claimed the ship. It ran aground near Isle Aux Morts and broke up after only a few hours. Barely three dozen survivors made it ashore, to face severe windy and wintery conditions on the isolated shore.

Most of them, led by an officer who struck out for the nearest major settlement, were never seen again, but hunters rescued other survivors who either broke off from the main group or were left behind. After wintering in Newfoundland, the seven remaining crewmembers eventually made it to Quebec City in the spring, bringing the first news of the disaster to the authorities.

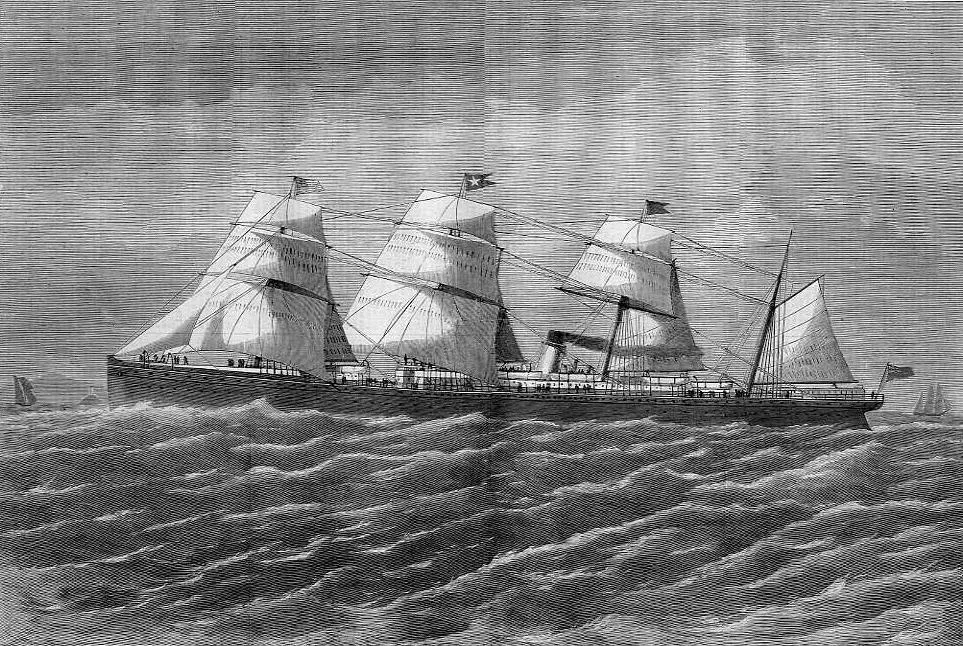

1873: RMS ATLANTIC

Image: Wikimedia Commons

This vessel was your run-of-the-mill ocean liner operated by the White Star Line – the same operator of the ill-fated Titanic – on one of its typical trips from Liverpool, U.K., to New York City, with passengers and crew numbering around 950.

It was making an approach to Halifax for resupply – again, nothing out of the ordinary – when it ended up 20 km off-course due to stormy conditions and poor visibility. After a series of crew missteps – including totally failing to notice the Sambro Lighthouse, whose specific purpose was to warn sailors away from the more treacherous patches of the South Shore – the ship hit a rock and quickly took on water.

Numbers are sketchy, but it seems more than 530 people never made it to shore, including almost all of the women and children among the passengers.

The maritime disaster held the dubious crown of being the deadliest in the North Atlantic for almost a quarter-century. It was the first of the White Star Line’s ocean steam liner fleet to sink. It was by no means the last.

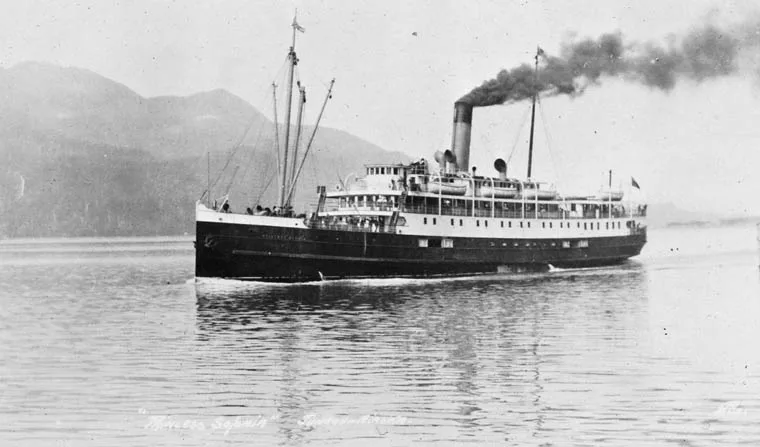

1918: S.S. PRINCESS SOPHIA

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Library and Archives Canada

Shipwrecks are woven into the fabric of Atlantic Canada’s history, but the West Coast has its own stories of deadly disasters at sea.

With a death toll of around 340, the wreck of the S.S. Princess Sophia is the worst in the history of British Columbia and Alaska. The B.C. ship left Skagway, Alaska, on a course that would eventually take it to Vancouver. Tossed by rough seas and strong winds and blinded by heavy snow, it struck a reef near Juneau, Alaska.

The Princess Sophia’s distress call did manage to reach the authorities, but the same conditions that drove it onto the reef kept rescuers from getting close enough to make a difference. Visibility was so terrible that when the Sophia did sink, no one could actually witness the ship’s final demise.

Historians have a pretty good idea as to how the ship's last hour unfolded, but they didn’t have any first-hand accounts to go by – there were no survivors.

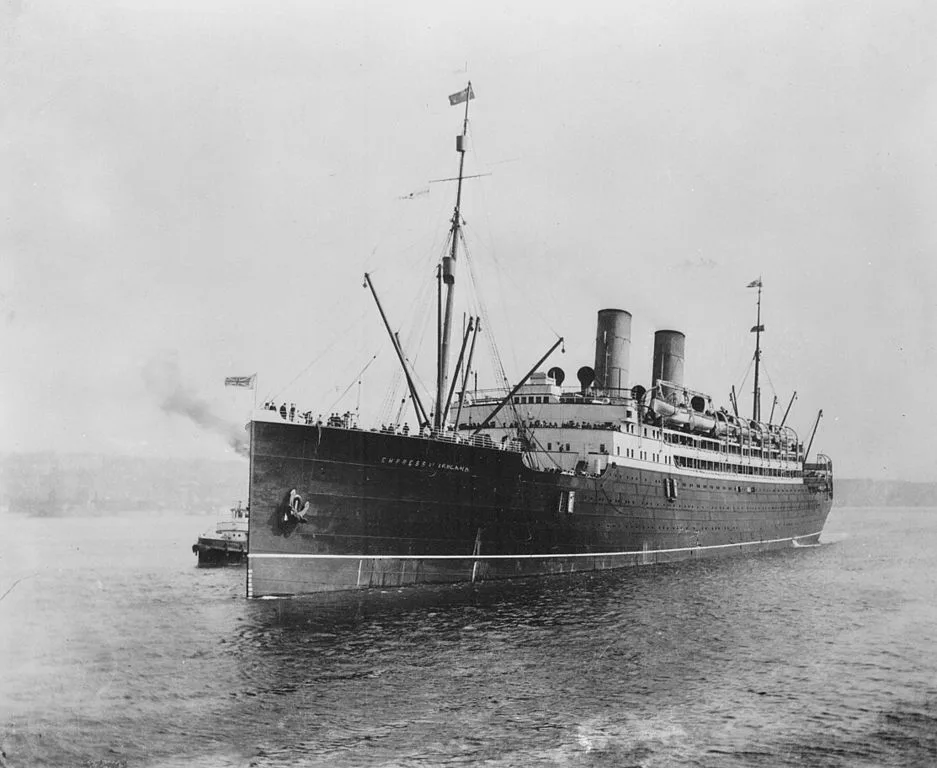

1914: EMPRESS OF IRELAND

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Library and Archives Canada

Canada’s deadliest peacetime maritime disaster didn’t happen at sea or even on the sometimes dangerous Great Lakes, nor did it even happen in stormy weather.

The RMS Empress of Ireland was sailing the wide-mouthed St. Lawrence River near Rimouski when it collided with the Norwegian vessel Storstad in heavy fog conditions.

The Norwegian ship made it, but the Empress was badly damaged, listing heavily. Water poured into the ship through portholes, left open contrary to maritime regulations, drowning many passengers before lifeboats could even be launched. Even then, only three lifeboats made it off before the deck was too slanted to continue.

By the time it sank beneath the waves, 1,012 people out of a complement of 1,477 lost their lives.

The wreck is actually at a relatively shallow depth, allowing scuba enthusiasts to visit, but dangerous diving conditions have reportedly claimed at least a half-dozen lives so far.

1917: HALIFAX EXPLOSION

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress

Canada’s deadliest non-natural disaster wasn’t even remotely weather-related, but we couldn’t leave it off the list.

Some two thousand people were killed after Norwegian ship S.S. Ivo collided with the S.S. Mont-Blanc, a French cargo ship heavily laden with explosives.

Mankind wouldn’t make a bigger explosion until the invention of nuclear weapons. As it was, the 2.9 kiloton explosion flattened Halifax and could be heard as far away as Montreal. Aside from the staggering death toll, thousands of people were made homeless and a substantial chunk of the city’s industry was wiped out.

The damage, adjusted for inflation, is estimated to have been the equivalent of a half a billion dollars in today’s terms, and the explosion left its mark in Canadian history: Only the Spanish flu and the Newfoundland Hurricane of 1775 had higher Canadian death tolls.

1975: EDMUND FITZGERALD

With 29 deaths, the Edmund Fitzgerald is actually on the low end of the shipwreck scale in terms of fatalities, but it’s arguably one of the country’s most famous, thanks in no small part to Gordon Lightfoot’s immortal song.

People still debate exactly how things unfolded, but the ship met its fate grappling with a violent storm characteristic of the “Witches of November,” powerful tempests that lash the great lakes that month. At times, the conditions can be the equivalent of a low-to-mid level hurricane.

They’ve been a menace as long as ships have sailed the lakes. Hundreds of vessels and thousands of lives have been sent to the bottom over the last three centuries.

The Edmund Fitzgerald sparked a host of changes to maritime warning systems and shipboard safety regulations. As for Gordon Lightfoot, he occasionally alters the original lyrics to The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald at live performances to reflect the results of investigations over the years.