Earth's new lightning capital of the world confirmed from space

Data collected from the International Space Station adds a new dimension to Earth's lightning.

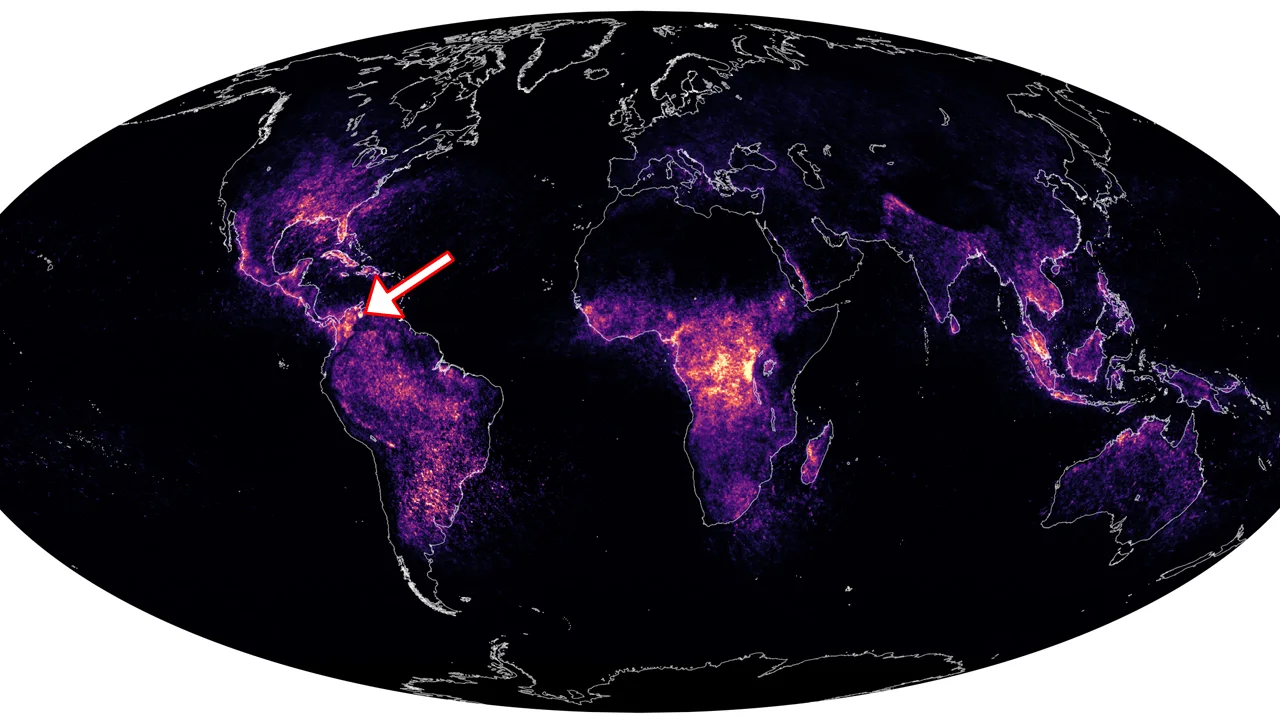

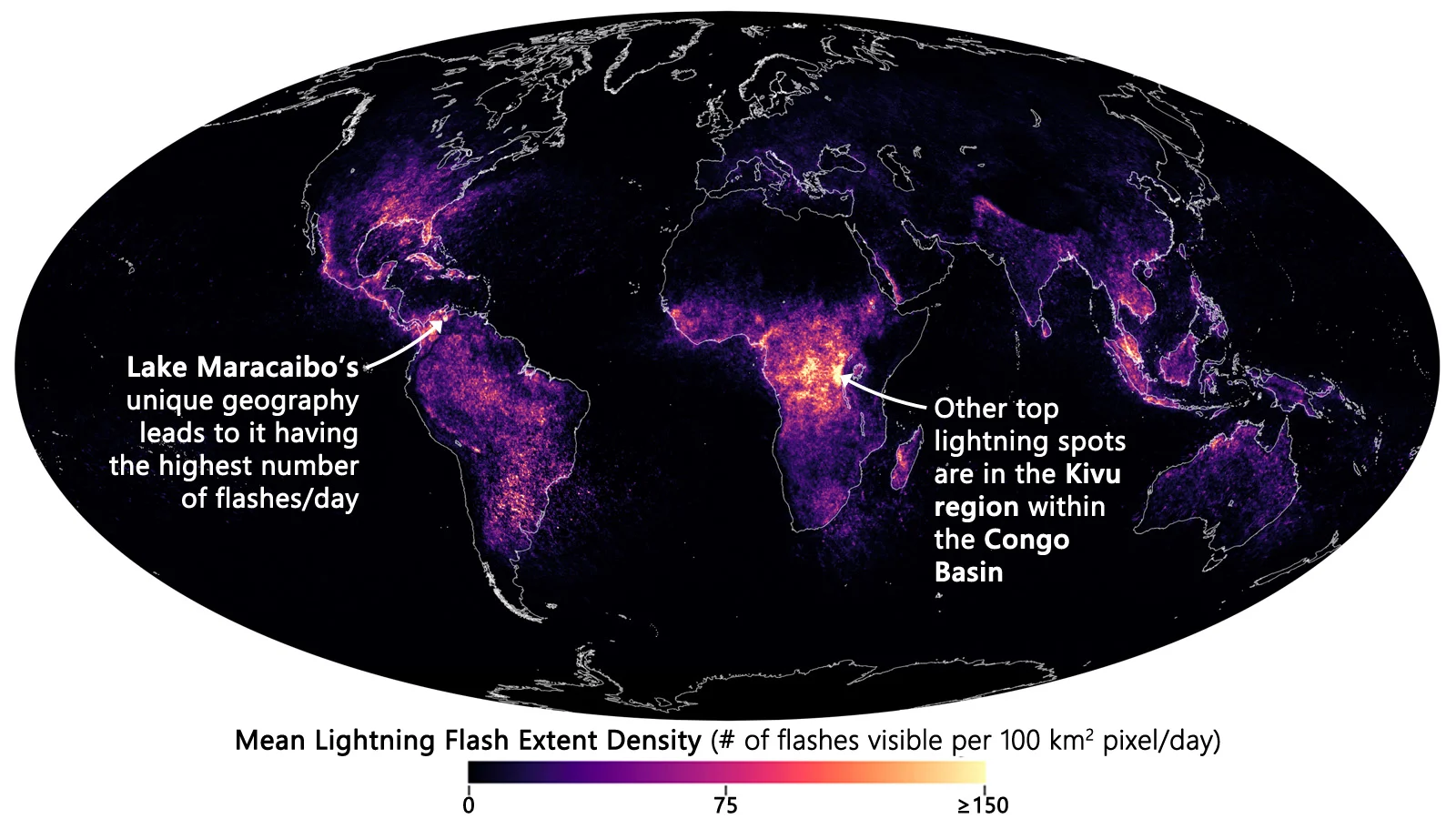

A new NASA map reveals how many times you can expect to see lightning flashes from wherever you live on the planet. It has also pinpointed a new lightning capital for the world.

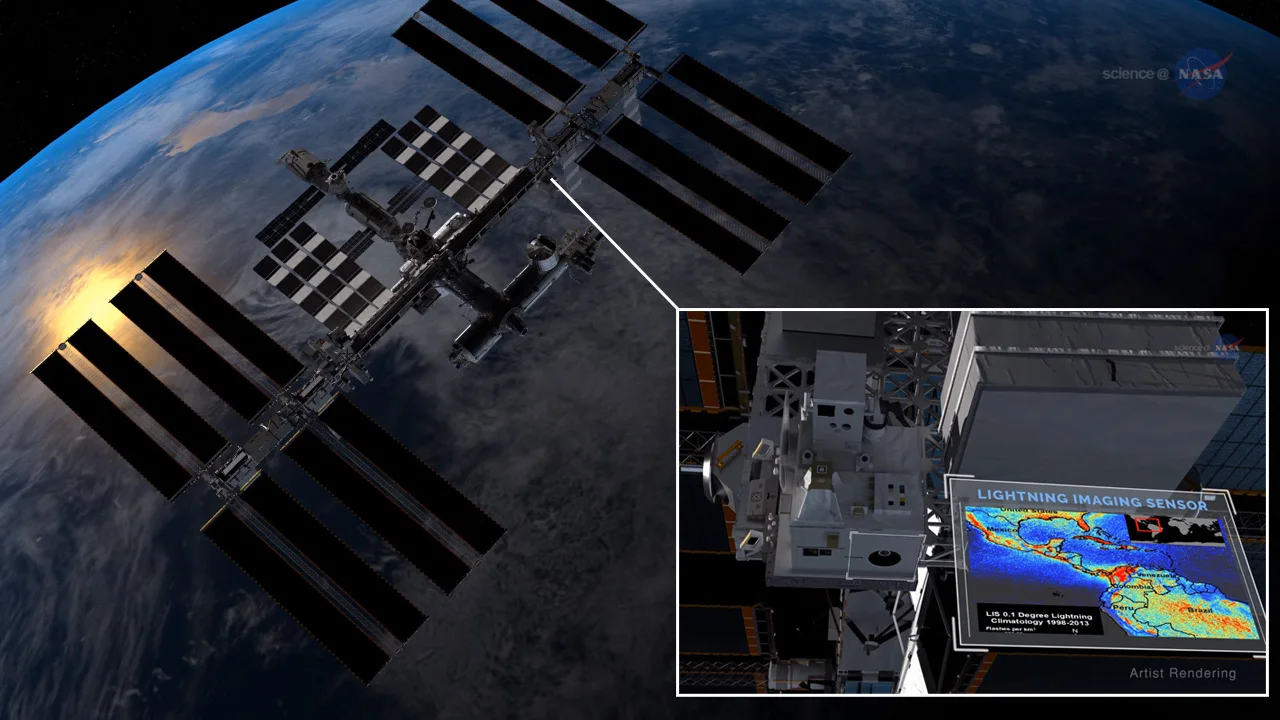

Attached to the outside of the International Space Station, circling the Earth 16 times every day, is a specialized science camera known as the Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS). This NASA instrument has been cataloguing lightning strikes in the atmosphere since 2017. It is the second LIS to be launched after the first flew on NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite from 1997-2015. It is also the third dedicated lightning instrument NASA has put into space. The first was the Optical Transient Detector (OTD) on the OrbView-1 satellite, which circled Earth from 1995 to 2000.

This artist's rendering shows the location of the Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) on the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

The Lightning Imaging Sensor's vantage point on the ISS provides far better data than the previous missions. It gives better resolution than OTD did in the 1990s, and it sees far more of Earth's surface than the LIS on TRMM could.

"What is new and notable about the ISS LIS is that it gives us observations that are significantly farther north and south than we got from TRMM," Patrick Gatlin, an atmospheric scientist at the Marshall Space Flight Center, said in a NASA Earth Observatory post. "ISS LIS observations extend to latitudes up to 55 North and 55 South, well into Canada and Patagonia."

According to NASA, the new LIS adds an extra dimension to the data.

The two previous lightning sensors, on Orbitview-1 and TRMM, simply logged the location of a lightning flash as a single point on the map. However, when a lightning strike occurs, there can be a substantial distance between where it originates and where it connects with another cloud or a point on the ground. Typically, the start and end points are within a few kilometres of each other, which easily fits within a single pixel on a world map. Some lightning bolts reach significantly farther, though.

On October 31, 2018, a lightning 'megaflash' stretched over 700 kilometres across the southern tip of Brazil.

To address this problem, researchers Michael Peterson of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Douglas Mach at the Science and Technology Institute of the Universities Space Research Association in Huntsville, AL, and Dennis Buechler from the Earth System Science Center at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, combined all of the lightning data collected from space. Their study turned the old one-dimensional point data into a brand new two-dimensional map that accounts for the horizontal distance a lightning strike can cover.

This map combines all lightning data from 1995 to 2020 reveals the extent of Earth's lightning, and pinpoints those regions that receive the most lightning per year. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

"Our analysis accounts for the fact that lightning bolts can spread horizontally, not just vertically from clouds to the ground," Peterson told NASA Earth Observatory. "One way to think about this new climatology is that it tells us the frequency that an observer can expect lightning to be visible overhead — regardless of where the flash began or ended."

This new lightning map also confirmed Earth's new lightning capital of the world.

At one time, the spot on Earth with the most lightning strikes was near Lake Kivu, on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. While Africa still has the greatest number of lightning hotspots, in 2016, new research moved the lightning capital over 11,000 kilometres to the west. It is now located at Lake Maracaibo, a large tidal bay in northwestern Venezuela.

"Located in northwest Venezuela along part of the Andes Mountains, it is the largest lake in South America. Storms commonly form there at night as mountain breezes develop and converge over the warm, moist air over the lake," NASA said at the time. "These unique conditions contribute to the development of persistent deep convection resulting in an average of 297 nocturnal thunderstorms per year, peaking in September."

Even with this new, updated analysis, Lake Maracaibo still retains its status.

Multiple lightning strikes flash over the dark waters of Lake Maracaibo. Credit: NASA

According to NASA Earth Observatory: "With an average flash rate of 389 per day, Lake Maracaibo in northern Venezuela (shown above) has the highest flash extent density in the world. That region's unique geography fuels weather patterns that make it a magnet for thunderstorms and lightning. The area along Lake Kivu, on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, is a close second with an average of 368 flashes per day."