It's December 1st! Welcome to meteorological winter!

Rather than the 'official' date of December 21, meteorologists mark the 1st of December as the true start of Winter.

According to the 2021 calendar, the First Day of Winter in the northern hemisphere isn't until December 21. However, for meteorologists and climatologists, it's actually on the 1st of December. Here's the story behind Meteorological Winter.

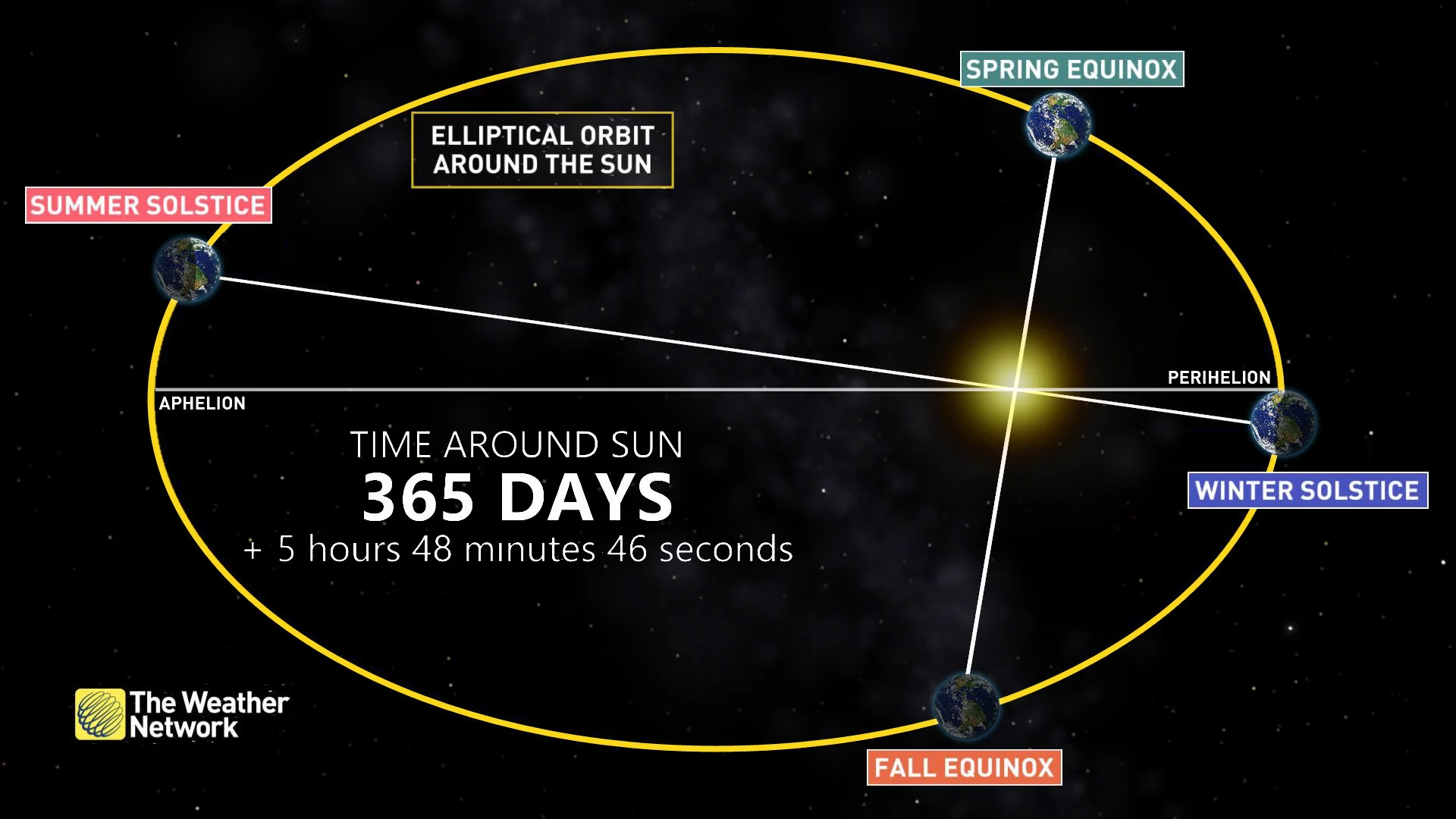

As we all know, our year is broken down into four seasons. In the northern hemisphere, spring starts in March, summer begins in June, fall starts in September, and winter begins in December. The exact day that each season starts on varies from season to season and year to year, but it's typically somewhere around the 21st of the month, give or take a day or two.

There's a very specific reason for this. Long ago, we noticed patterns to the motion of the Sun across our skies. In addition to crossing from east to west each day, how high the Sun reaches in the sky also changes — for half of the year it gets higher and higher above the horizon, and for the other half, it gets lower and lower. The reason for this day-by-day change is the fact that our planet is tilted on its axis, by approximately 23.4 degrees. So as we orbit around the Sun, it's position 'above' the planet changes.

This cycle is how we define our astronomical seasons.

Spring starts at the Vernal Equinox, when Earth is in just the right spot in its orbit so that the Sun appears to cross the equator towards being higher in the sky, and both hemispheres of the planet are lit equally by the Sun's light. Summer begins at Summer Solstice, when the Sun reaches its peak height in the sky. Autumn or Fall begins at the Autumnal Equinox, as the sun appears to cross the equator headed towards being lower in our daily skies. Winter starts at Winter Solstice, when the Sun reaches its lowest height in the sky. Then the cycle repeats.

Using astronomical timing to define our seasons has worked for a long time, so there's no need to go changing that now. However, these dates do not necessarily line up with our seasonal weather and climate. Also, they definitely don't mesh well with how we keep records of weather conditions throughout the year.

SHIFTING ALIGNMENT

When keeping weather records, consistency is essential. Daily, weekly, monthly, and even yearly records maintain this consistency, since these time periods are always the same (except for leap years). Thus, atmospheric scientists can easily make comparisons, find extremes, and track trends.

Comparing seasons and seasonal trends is important too, but astronomical seasons throw an added complication into the process. They are anything but consistent. Due to slight changes in the timing of both our orbit around the Sun and the rotation of Earth, the equinoxes and solstices change from year to year. This changes the exact time during the day that each season starts and ends, and the lengths of the seasons can vary as a result. For example, Spring of 2021 began on March 20, at 5:37 a.m. EDT, and it ended on June 20, at 11:32 p.m. EDT. In 2022, the same season begins on March 20, but at 11:33 a.m. EDT, and it ends on June 21, at 5:13 a.m. EDT.

This 'solargraph' image was produced by leaving a pinhole camera aimed at the Toronto skyline for 113 days in 2016. The image captures the Sun's path across the sky for each day from February 28 to June 20. Credit: Bret Culp (Used with permission)

It's not that comparisons can't be made, of course. These days, computers can easily tally up all the weather records between the precise start and end times of any astronomical season (although applying adjustments and corrections to make the comparisons more accurate would be bothersome).

Over 200 years ago, when the first meteorological network was set up (Societas Meteorologica Palatina), such a task would have been a far more cumbersome and time-consuming.

To align the seasons better with how meteorological records were kept, meteorological seasons were created.

Each meteorological season is still three-months long, but unlike astronomical seasons, they start and end on exactly the same dates from year to year, and they align precisely with our calendar months. Meteorological spring begins on the 1st of March, meteorological summer starts on the 1st of June, meteorological fall begins on the 1st of September, and meteorological winter starts on the 1st of December.

DOES IT MAKE THAT MUCH OF A DIFFERENCE?

Meteorological seasons are useful for more than just bringing consistency to seasonal comparisons. As it turns out, they are also well-timed to capture the most 'representative' weather of each season.

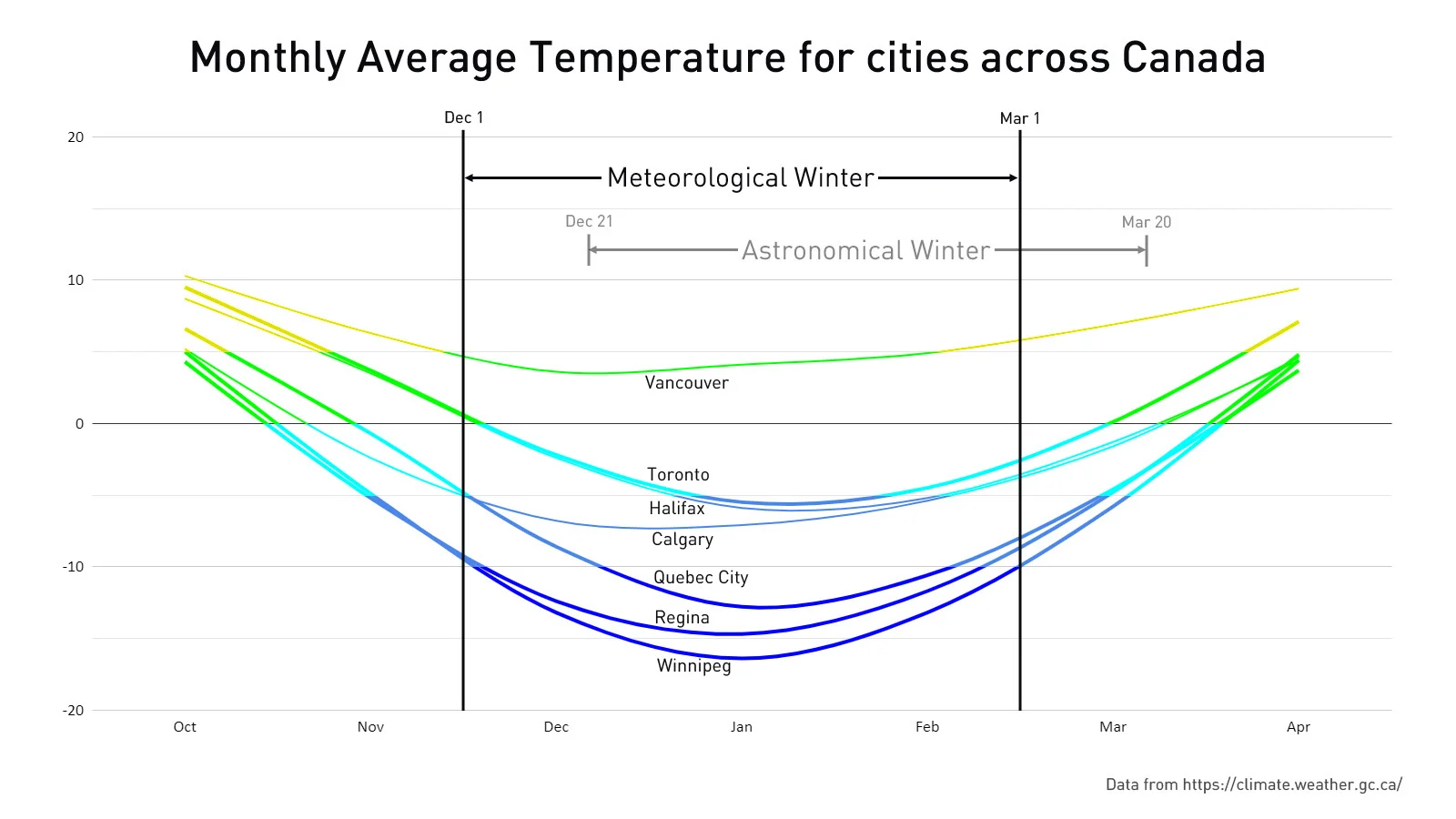

As the graph above shows, while some of these Canadian cities experience much colder winters than others, nearly all of them follow a similar temperature trend throughout the season.

With both the meteorological and astronomical seasons plotted on the graph, meteorological winter definitely captures the coldest part of that temperature trend far better than its astronomical counterpart.