Seven times weather unexpectedly changed the course of history

History books are full of tragic storms, but there are plenty of major global events that were silently shaped by the weather on those fateful days.

Weather is history. Storms are woven into our national stories as much as battles and revolutions or trials and triumphs. The powerful blow of a hurricane or tragic spark of a wildfire can raze neighbourhoods and form community bonds that last for generations.

But for all the disasters that dot our historical landscape, there are just as many significant events that were silently driven by weather conditions that wound up changing the world.

DON’T MISS: Do you love weather and history? Every episode of This Day in Weather History is now available—check it out!

September 11, 2001

Every recounting of the horror of the attacks on September 11, 2001, starts with a description of the crystal clear skies that blanketed the U.S. East Coast that morning.

History is so full of torrential storms that 9/11 stands out as one of the few instances where so many people remember a complete lack of active weather. The sky was a stunning shade of blue that Tuesday.

A potent cold front swept through the eastern U.S. the night of September 10th, bringing the region its first taste of fall after a long, hot summer. The front triggered rain and thunderstorms the night before, with low clouds and poor visibility throughout the Interstate 95 corridor.

The timing of the cold front changed the course of world history. If it had come through a little bit slower, the weather that Tuesday morning may have caused flight delays or cancellations that would’ve altered the events that unfolded in the hours to come.

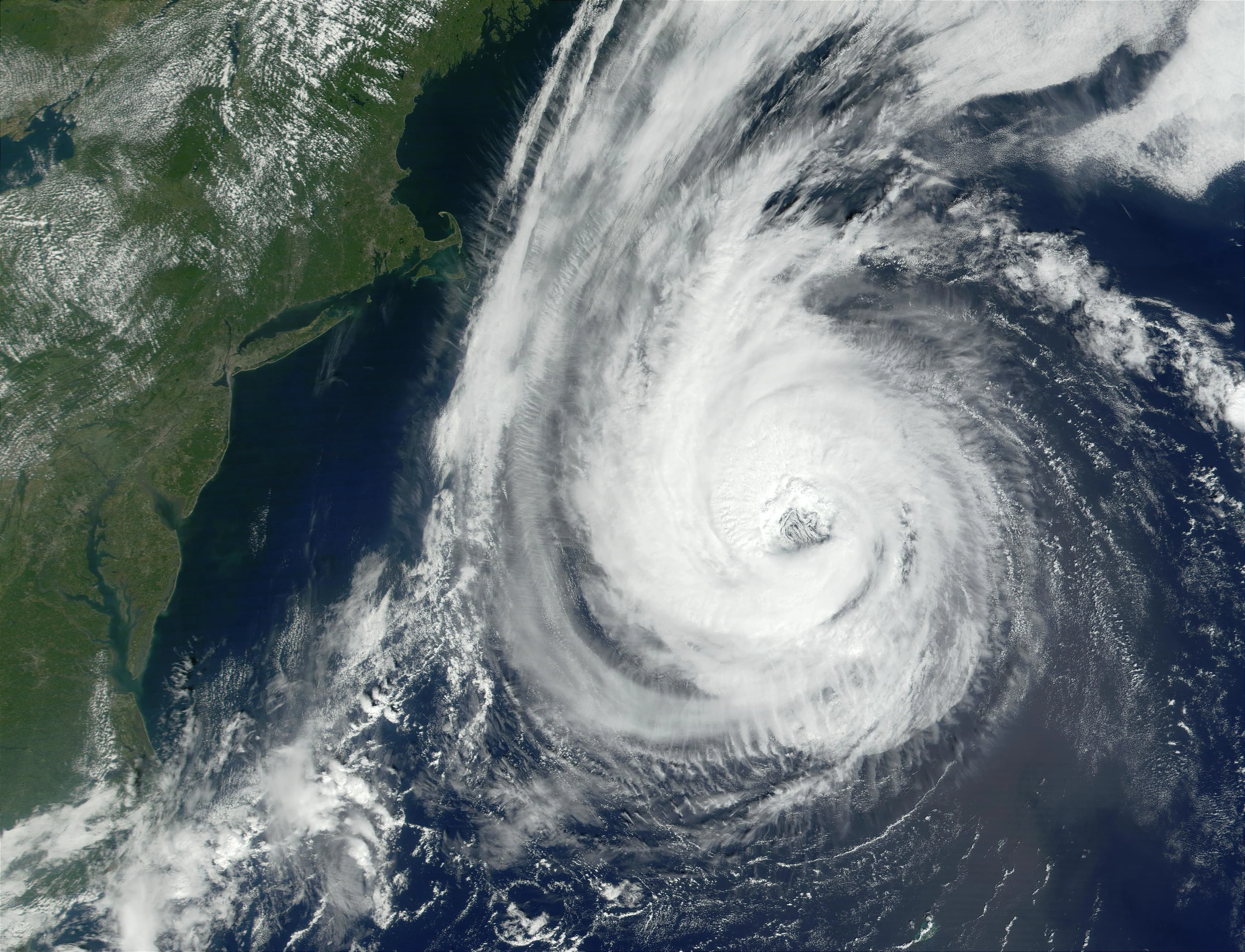

Hurricane Erin swirls off the U.S. East Coast on September 11, 2001. A plume of smoke is visible drifting south from New York City’s World Trade Center. (NASA)

Forgotten in history is what else was lurking off the Atlantic coast on September 11th: Hurricane Erin.

The trough that brought the cold front over the eastern seaboard also shunted a strong hurricane away from the coast. If the trough had been slower, Hurricane Erin may have come closer to the U.S. or even threatened landfall.

WATCH: A hurricane hit Newfoundland just days after 9/11

Space Shuttle Challenger

Unusually cold temperatures blanketed Florida’s Space Coast on the morning of January 28, 1986. A typical morning low temperature at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center would come in around 10°C at the end of January. In the midst of a cold snap across the eastern U.S., though, the temperature that morning dropped to a frigid -4°C.

The seven-member crew of STS-51-L strapped into the Space Shuttle Challenger and prepared to take flight on a six-day mission that would see the first civilian teacher, Christa McAuliffe, fly into orbit.

73 seconds after liftoff, the shuttle and its launch vehicle were destroyed while flying faster than the speed of sound.

Space Shuttle Challenger lifts off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on January 28, 1986. The vehicle exploded 73 seconds into flight. (NASA)

The vehicle’s right solid rocket booster began venting superheated gas out the side of the rocket, burning into the external tank and causing the entire structure to fail. The explosion and subsequent impact with the ocean killed all seven crew members.

After a yearslong investigation, NASA found that the bitterly cold temperatures that morning played a crucial role in the Challenger’s failure. A seal inside of the right solid rocket booster failed because it stiffened in the subfreezing temperatures that morning, allowing superheated gas to bypass the failed seal and set off a chain of events that led to the orbiter’s destruction.

While errors in judgement on the ground played a significant role in the tragic disaster, that unusually cold morning along the Florida coast was the spark that ultimately led to the loss of the Challenger and its crew.

A blizzard immediately followed one of Canada’s worst disasters

The collision of two ships in Halifax Harbour on December 6, 1917, triggered a horrendous explosion that remains today one of the largest and deadliest disasters in Canadian history.

The unthinkable happened that afternoon when the SS Mont-Blanc collided with the SS Imo between Halifax and Dartmouth. The Mont-Blanc, carrying a significant haul of explosives headed to France, caught fire in the collision and exploded a short time later.

More than 1,700 people died when thousands of buildings were razed by the explosion and its subsequent tsunami. Thousands more were seriously injured. It was an unprecedented disaster at the time, and the people of Halifax relied on help from rescuers as far away as Boston.

Unfortunately, another disaster struck just two days later. A tremendous blizzard swept up the coast and dropped 40 cm of snow on Halifax, significantly slowing down relief and recovery, and making the lives of survivors even harder in their time of dire need.

CHECK IT OUT: Looking back at the Halifax explosion, 100 years later

RELATED: Secrets of Canada's seven most famous shipwrecks

World War II gave us weather radar

Allied soldiers scanning the skies for enemy aircraft during the height of World War II spotted more than they expected when the weather turned foul.

Troops noticed that strange blobs showed up on their radar screens during rain showers. Scientists quickly took advantage of this anomaly and, within just a few years, began using radar to scan the skies for storms instead of fighters.

Today, hundreds of advanced weather radars scan the skies over Canada and the United States, capable of spotting strong winds, hail, and even tornado debris lurking within a storm.

DON'T MISS: This deadly plane crash made flying safer—and improved weather warnings

Weather factored heavily into the U.S. nuclear bombings of Japan

Weather played a critical role in the United States’ atomic bombings of Japan in August 1945. American troops dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima from clear skies on August 6th, with the second bomb detonated over Nagasaki three days later on August 9th.

The two bombs killed hundreds of thousands of people in the deadliest single attack on civilians in world history. The crews that deployed the two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki relied entirely on clear skies to carry out the attacks.

DON’T MISS: How the weather helped (and hindered) at Vimy Ridge

Cloudy skies inhibited their ability to see their target and photograph the aftermath—a fact that saved the city of Kokura, known today as Kitakyushu, which was the initial target for that second bombing. The nuclear-armed aircraft arrived to find dense clouds over Kokura, forcing the crew to divert 150 km southwest to Nagasaki instead.

PODCAST: Hurricane-like winds blew a 'wall of fire' across Tokyo during WWII

Bad habits and intense drought created the historic Dust Bowl

We’re familiar with the long-term effects of anthropogenic climate change, but our daily activities can affect weather conditions in ways that have huge ramifications later on.

Poor farming practices in the early 1900s would lead to one of the greatest environmental catastrophes in modern times. Through a combination of overplowing and overgrazing, farmers destroyed the vital grasses that held together the soil on the Plains.

When a years-long drought settled over the American heartland, the topsoil on that mismanaged land turned to fine dust that blew away in the wind.

The resulting dust storms were epic. One particular dust storm in April 1935 was termed “Black Sunday” because the mammoth wall of dust completely blotted out the midday sun.

The one-two punch of the unprecedented drought and the Great Depression led to the failure of tens of thousands of farms. The ordeal sparked a revolution in sustainable farming and land management methods that are still in use today.

PODCAST: The 193-vehicle pileup that caused 40,000 lbs. of fireworks to explode

Rain may have elected at least two U.S. presidents

Gloomy weather can stop us from running to the store or grabbing a bite to eat, but can it dissuade us from choosing our next leaders?

American political scientists have spent decades studying and debating whether the weather can help pick the country’s next commander in chief. The theory, it goes, is that only the most dedicated partisans will slog through puddles to pull the lever for their favourite candidate.

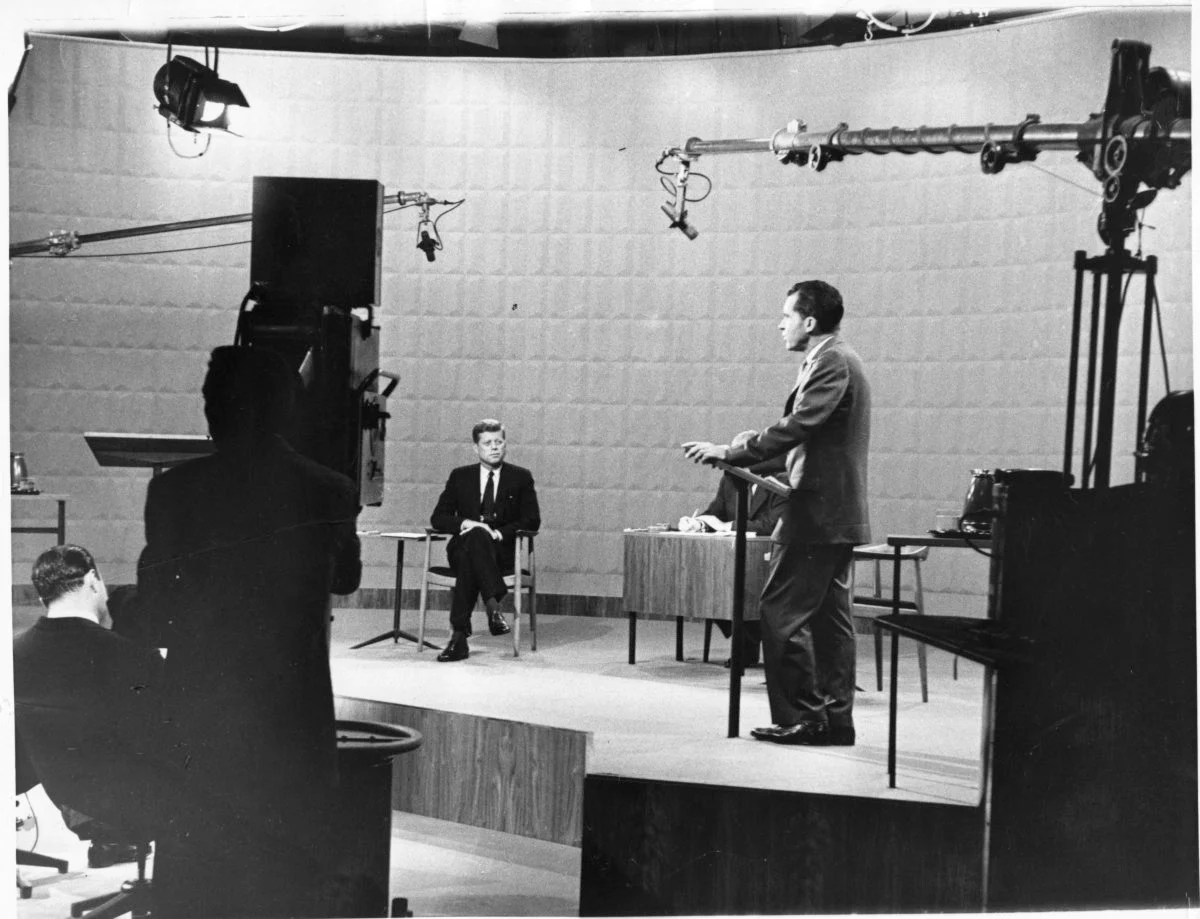

Sen. John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard Nixon participate in the first-ever televised presidential debate on September 26, 1960. (Richard Nixon Library/National Archives)

A 2007 study conducted by a group of political scientists looked at both weather data and election results for the 14 presidential elections conducted between 1948 and 2000 to find out if rain really can swing elections.

What the researchers found, they argue, proves that weather is not only determinative, but it may have swung the results of two closely fought races.

The election of 1960 saw Senator John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, challenge then-Vice President Richard Nixon for the country’s top job. Kennedy ultimately won the close race by a few thousand votes in just a handful of states.

Researchers found that Kennedy’s ascension to the presidency was likely aided by good weather across the country on November 8, 1960. The pleasant conditions that prevailed that Tuesday likely boosted voter turnout and encouraged infrequent voters to head to the polls, handing Kennedy the White House.

President George W. Bush and former Vice President Al Gore shake hands at Bush's inauguration on January 20, 2001. (White House/National Archives)

Foul weather on November 7, 2000, on the other hand, likely contributed to the historically close result between Governor George W. Bush and Vice President Al Gore. The outcome infamously came down to a few hundred contested ballots in Florida, dragging on for more than a month before the Supreme Court stepped in to put an end to the recounts.

A fight over hanging chads wasn’t the only storm looming over Florida that day. Rain in certain parts of the state likely drove down voter turnout among key constituencies, boosting Bush’s margin. If the weather was a bit nicer in Florida that day, the researchers argue, it’s likely that Gore would have won the state instead—and with it, the presidency.

Thumbnail image courtesy of NASA.