Six of the world's weirdest (and sometimes dangerous) lakes

Sometimes, a pretty, insta-worthy landscape hides a nasty secret.

We wrote this week about a mysterious blue lagoon in Derbyshire, England, popular with shutterbugs for its electric blue hue -- which is a problem for any who wade in, given its alkalinity is about on a par with bleach or ammonia.

We took a look around, and here are six other striking lakes with sometimes harmless, sometimes dangerous secrets.

LAKE HILLIER

It’s okay for you to look at Western Australia’s Lake Hillier and think: “Okay, bad Photoshop.”

Image: Kurioziteti123/Wikimedia Commons

First sighted by Europeans in 1802, the lake is on Middle Island on the Recherche Archipelago off the state’s coast. It probably did exactly nothing to dispel the 19th Century popular imagination of Australia as the freakiest continent on Earth.

Around 600 m across, surrounded by lush forest and separated from the ocean by a narrow strip of land, it’s a colourful sideshow in paradise.

Most sources we looked at, including Australia.com, say the pink colour probably comes from bacteria living in salt crusts in the lake (another lake nearby, actually called “Pink Lake, has a similar look).

Image: Wikimedia Commons/PruneCron

The site says you can only view it by air, but this tourism site has pictures apparently taken from the shore (it also says the bacterial excretions would be harmless to swimmers).

You can take a cruise to the area (there’s plenty to do and see), or you can do what Red Bull athlete Chuck Berry did, and admire Lake Hillier by wingsuit:

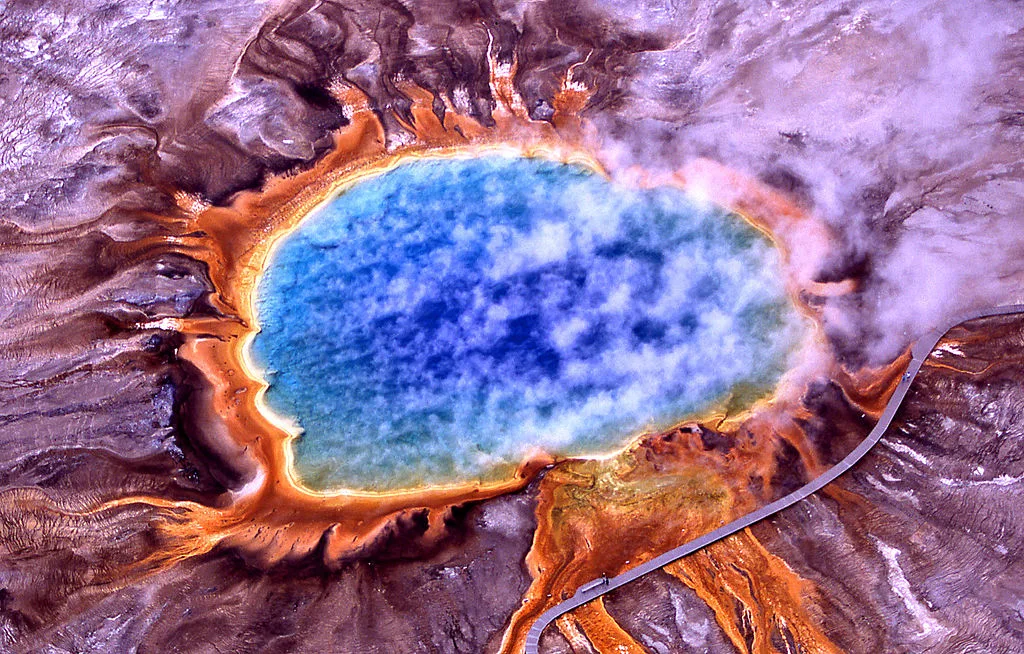

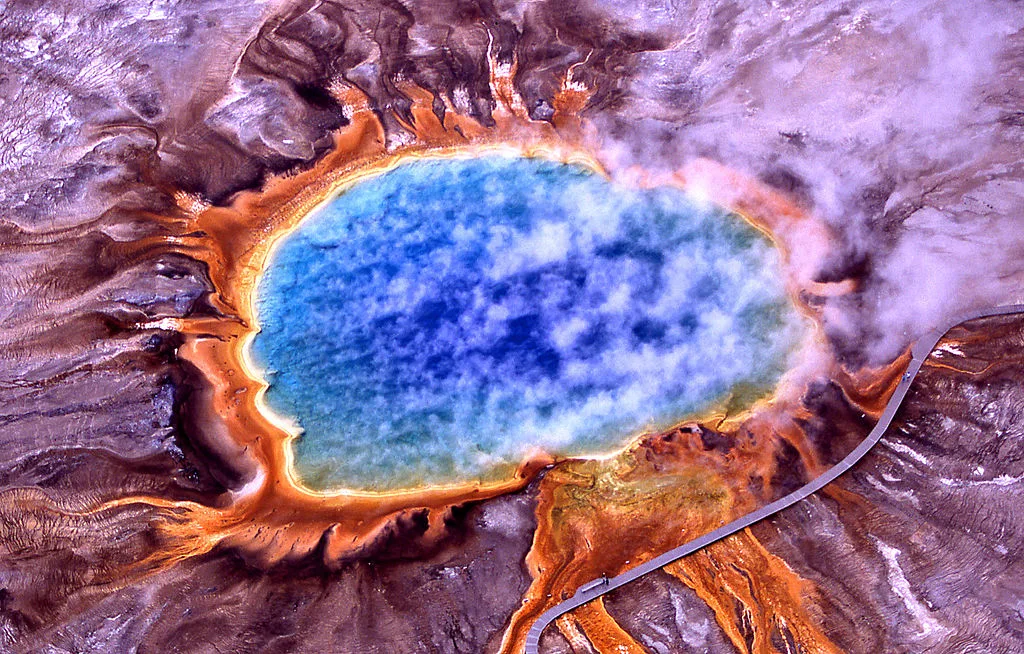

GRAND PRISMATIC SPRING

In a similar vein to Lake Hillier, here’s a case where it’s less “bad Photoshop” and more “bad acid trip.”

Image: Jim Peaco/National Parks Service

The Grand Prismatic Spring, in Yellowstone National Park, really does look like that, with those vivid colours in rings around the boiling centre. It’s the largest hot spring in the United States, and the third hottest in the world.

How hot? This Smithsonian Magazine article about the science behind the spring says it’s 87°C in the centre, not far from boiling, whereas the outermost ring gets to around 55°C.

Those temperatures explain the colours. The centre of the spring is much too hot for any life to survive, so there’s nothing clouding the water to take away from the vivid blue of refracted sunlight.

The further you get, the cooler the water becomes, and the easier it is for highly specialized (and hardy) bacteria to thrive, although depending on water temperature they’ll take on different pigments for photosynthesis (Smithsonian explains it better).

Image: Miguel Hermoso Cuesta/Wikimedia Commons.

It was known to Native Americans before a fur trapper encountered it in 1839, and it was officially described by a survey mission in the 1870s. These days a small admission fee will get you access to a boardwalk that will take you quite near it.

Just don’t leave the boardwalk. The tourist in this YouTube video was fined $125 for leaving a boardwalk near another spring in the park. Park Rangers won’t look any more kindly on you if you try that near the more colourful spring.

They’re not fond of drones either. In 2014, a tourist was fined $3,000 for crashing a drone in the spring (rangers couldn't retrieve it because they couldn’t find its exact location and don’t want to disturb the area in a wide-ranging search). Another visitor who did the same thing was banned for a year.

Image: James St. John/Wikimedia Commons

It’s a heck of a natural treasure under close supervision, and its custodians take their jobs very, very seriously.

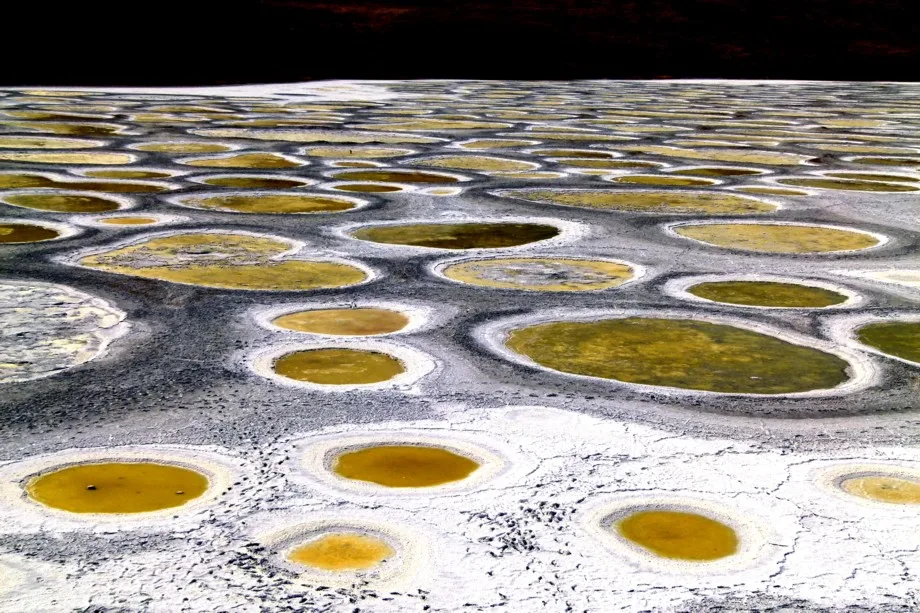

SPOTTED LAKE

Here’s a weird natural wonder, right here in Canada, near Osoyoos, B.C.

Image: Robin Carmichael

Local First Nations people call it Khiluk Lake, but it’s also commonly known as Spotted Lake, for reasons that are quite apparent.

It’s packed with more than a dozen different minerals, including magnesium, calcium and sodium sulphates, so when the lake’s waters evaporate in the summer, sometimes colourful crystals get left behind in those little pools.

Depending on your vantage point, they can reflect the sky and landscape to make for some intense hues.

Image: Dan Lybarger

But even this multi-coloured spectacle apparently can’t exist without some kind of bad history. First Nations people in the area consider its waters, purported to have healing properties, sacred, but that wasn't enough to deter developers who tried to build a health spa on the site.

Public and political pushback put paid to the plan, but decades later, a new development scheme would have seen tons of the mud in the area trucked away for spa treatments … possibly in California.

Image: Dee Newman.

That plan didn't make it either (you can read the story of the back-and-forth by Michael Kluckner here). Now although the land is on private property, you can still get a glimpse of it from the fence surrounding it.

LAKE RESIA

They say nothing can stop progress, and the former inhabitants of the town of Graun in South Tyrol, an Italian region with strong German and Austrian roots, know that quite well.

They completely lost their homes due to the development of hydroelectric power in the region. Well, maybe ‘lost’ isn’t the right word. They knew quite well where their town went: Right beneath the waters of Lake Resia (also known as the Reschensee):

Image: Noclador/Wikimedia Commons.

That 14th Century bell tower sticking up out of the lake is all that remains visible of Graun. According to Mental Floss, developers drew up plans for a hydroelectric dam in 1939, but it wasn’t completed until 1950.

In the path of the rising waters were more than 150 buildings and 500 hectares of farmland, according to the South Tyrol tourism department.

You can see shots of the town as it used to be in the German-language documentary below, about 15 seconds in.

Some of the former inhabitants used their compensation money to move away, but some stayed on, starting again in Upper Graun on the water’s edge.

In the meantime, the submerged town has become a big tourist draw for the area. In winter, you can even skate near the bell tower, as the ice can reach a thickness of 40 cm. The local tourism department even sets up speed skating tracks.

Image: Llorenzi/Wikimedia Commons

It honestly looks like great fun. Though if there are any still-living denizens of Old Graun, we wonder what they’d have to say about their former home becoming just another stop on someone’s Alpine road trip.

ROOPKUND

Roopkund, called “mystery lake” for reasons that will shortly become horribly clear, seems no different from any other glacial lake in the mountains of northern India. Until you get close up.

That’s when the illusion of tranquil seclusion gets a little tarnished by the skeletal remains littering the lake’s shores.

During the few weeks where Roopkund is unfrozen, the bones are visible in the clear mountain waters of the lake itself.

Most of the bodies, around 200 in total, show evidence of crushing blows from above, to the head and shoulders, according to this article in The Hindu newspaper. The British forest guard that discovered them while exploring the area in the 1940s must have had a bit of a shock, especially since back then the threat of Japanese invasion seemed very real.

The theory that the doomed group were Japanese forces didn’t last long, as the bones were much too old. The spooky circumstances fired up the popular imagination, which reckoned the bodies belonged to everything from the forces of a lost Kashmiri general, to ritual suicide.

Image: Schwiki/Wikimedia Commons

And when a National Geographic Expedition retrieved 30 bodies for DNA testing in 2003, it got even weirder: According to India Today, a large amount of the dead were from the same family, dating back the mid-Ninth Century.

Finally, scientists hit upon the answer: Rather than bandits or avalanches, the travellers all died beneath a massive barrage of cricket-ball sized hail, explaining the position and nature of the wounds.

Image: Schwiki/Wikimedia Commons

Hail that size isn’t common, but it does happen. In Canada and the U.S.’ tornado alley, hail can reach the size of toonies, golf balls, softballs and larger.

Without the benefit of vehicles or buildings to shelter in up in the mountain wilderness, those travellers would have been totally at the mercy of whatever violent storm produced the hail.

LAKE GUATAVITA

It’s an old cliché: A grizzled band of Spanish conquistadors, far from home and low on supplies, plodding deeper and deeper into the endless jungle in a fruitless search for El Dorado, the lost city of gold.

There never was such a thing, but there’s one place, Lake Guatavita, where the legend contains a grain of truth, and more than a few grains of actual gold.

The small lake was the centre of a religious ceremony of the Muisca people. On the day a new chief was chosen, he would be covered in gold dust, and rowed on a raft to the centre of this lake. He’d toss several gold artifacts into the waters as an offering to the goddess Chie, then hurl himself in last, emerging as a consecrated chief.

The peoples of that part of Colombia were expert goldsmiths, as can be seen by this golden sculpture of the chief’s raft, cast whole from excellent quality gold.

It was found in a nearby cave, not the lake, but the Spaniards, and many, many others, figured since they were plundering the rest of the Americas they might as well plumb Lake Guatavita’s depths for the rest of the treasure.

This post at Manhattan Gold and Silver (we guess they’d know about these things) includes some highlights. The Spaniards first tried to drain the lake in the 16th Century, via non-stop bucket chain. They only managed to lower the water level by three metres, but exposed enough gold artifacts estimated at hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Image: Jononmac46/Wikimedia Commons.

Another expedition brought the water levels down by 20 m, but the draining mechanism collapsed, killing several workers. Yes, the search for gold cost lives.

Finally, in 1898, a major effort almost emptied the lake. But that only made it worse: The lake bed was a morass of mud that was unsafe to traverse, and the sun soon baked it as hard as concrete. The expedition only uncovered a few hundred British pounds’ worth of items.

And still, it didn’t stop. This source details a number of failed 20th Century attempts before the Colombian government forbade any more.

And anyway, the author says, despite the prevailing idea that the best treasure was still in the deepest depths, by now there’s probably not much left.