Stunning jellyfish sprite seen in the night sky during Texas storm

These bizarre upper atmospheric flashes are still a mystery.

Thunderstorms can produce impressive displays of lightning, but one of the most spectacular and mysterious is the red sprite.

Every day, the Earth and its atmosphere exchange trillions of volts of electricity, as millions of lightning strikes flash to and from storm clouds around the world. At the same time that the ground and clouds pass this charge back and forth, there is also something going on above the clouds.

Brief flashes of light occur - there and gone in a fraction of a second - forming bizarre shapes that are spotted high in the night sky. These upper atmospheric phenomena are collectively known as transient luminous events. One of the most common types seen is the red sprite.

The image above was captured at around 1:30 a.m. Central Time on July 2, 2020. The photographer, Stephen Hummel, is the dark sky specialist at the McDonald Observatory, atop Mount Locke in West Texas. According to the Observatory's Twitter account, a powerful thunderstorm had developed around 150-200 kilometres to the southeast. What Hummel captured here is a jellyfish sprite, high above that storm.

According to Hummel, this sprite is the largest he has ever seen. Viewed from this angle, the bright 'heads' of the sprite are all at the same altitude, Hummel said, and the immense display is over 50 kilometres tall and stretches over 50 kilometres across.

"Jellyfish sprites are the briefest, brightest, and most intricate of the sprite family, and may be caused by exceptionally powerful positive lightning strikes," Hummel said in an email to The Weather Network.

There are three types of sprite that have been observed. Besides jellyfish, there are column sprites, which appear more as tapered cylinders of light. There are also carrot sprites, which are column sprites with long tendrils underneath.

These column and carrot sprites were captured during a 1994 NASA/University of Alaska aircraft campaign to study the phenomenon. Credit: University of Alaska Fairbanks

Sprites are not exactly rare. To see them, you need to be in the right place and at the right time and know what to look for.

"Sprites themselves are not particularly rare during severe storm season," Hummel added, "they're just difficult to catch."

This requires being far enough away so that you can clearly see the area above the storm. It also helps if there's a clear dark sky above the storm, and there are no bright sources of light pollution in the area.

"Sprite producing storms usually occur in late spring to mid-summer for our location [in west Texas]," Hummel said. "In May of this year, sprites were exceptionally common; for over a week straight, I saw them every night."

WHAT IS A SPRITE?

So, what's going on here? What exactly is a sprite?

Sprites are rapid flashes of red light that occur high up in the mesosphere, over 50 kilometres above the ground. Similar to how lightning is an electrical discharge between a cloud and the ground, sprites are electrical discharges between the top of a thunderstorm and the upper atmosphere.

It seems that we've known about them, or at least transient luminous events in general, for nearly 300 years. According to NASA's Earth Observatory, pilots apparently were reporting sightings of them since the first military and commercial flights in the early part of the 20th century. It wasn't until 1989, though, that they were finally caught on camera.

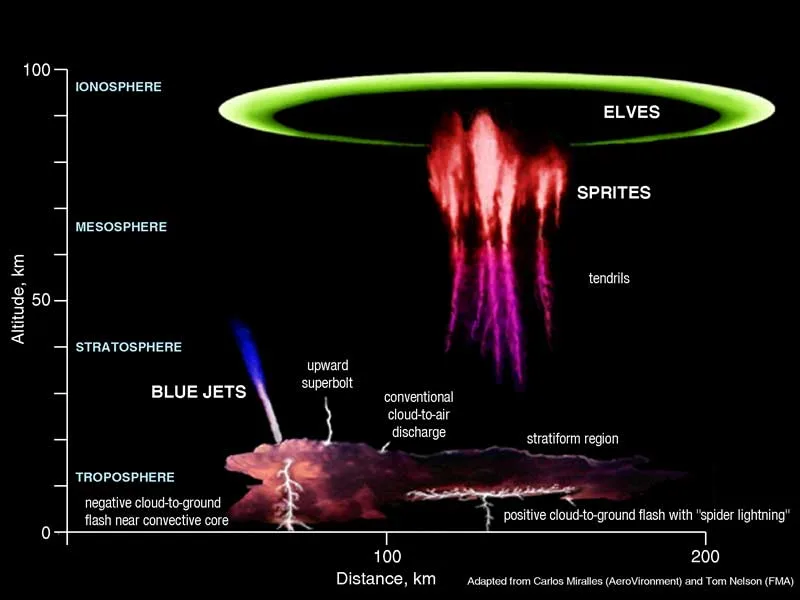

The different forms of transient luminous events. Credit: NOAA

Sprites are often considered to be a type of upper atmospheric lightning. While both sprites and lightning involve the movement of electric charge through the air, though, that is really where their similarities stop.

Lightning happens only in the lowest level of the atmosphere - the troposphere. Also, the air a bolt of lightning passes through reaches temperatures several times hotter than the surface of the Sun. Sprites, on the other hand, only occur in the upper atmosphere - in the mesosphere and ionosphere - and they are a cold plasma phenomenon. Their glow probably has more in common with that of a fluorescent light bulb.

The colour of a sprite comes from the fact that our atmosphere is mostly nitrogen. When an air molecule becomes energized, it will emit a flash of light to dump that excess energy. In the case of nitrogen, the light emitted has a very strong red component, along with a bit of blue and purple.

WHAT CAUSES SPRITES?

While we know what sprites are, basically, explaining how they form is far more challenging. Here's what we know and what researchers speculate about the process.

Part of the story starts inside a thunderstorm, where the exchange of electrons between colliding ice crystals and snow pellets results in distinct regions of electric charge within the cloud. Weak positive charge collects at the base, strong negative charge accumulates in the middle, and strong positive charge builds at the top. Lightning flashes occur within the cloud, or with a nearby cloud, or between the cloud and the ground, to balance this charge separation. Typically, this is a negative lightning strike balancing out the negative charge in the middle of the cloud with some point of positive charge in the ground.

The likely distribution of electric charge has been drawn onto this UGC image of a storm cloud taken on July 17, 2020, from Skyview Ranch, Calgary.

The process of sprite formation above the cloud appears to also involve the balancing of charge separation. One half is likely the positive charge that accumulates in the upper atmosphere, as air molecules are bombarded by intense solar radiation during the day. The negatively charged centre of a thunderstorm cloud has the potential to balance the positive charge high above. However, the positive charge accumulated at the top of the cloud stands in the way.

Lightning isn't only negatively charged, though. There is also positive lightning that balances out the positive charge buildup at the top of the storm with the ground. When this happens, the negative charge lower down in the cloud becomes exposed directly to what's going on above.

Based on observations, sprites are almost always preceded by one of these positive lightning strikes. So, this could identify them as a potential trigger for the phenomenon.

However, while nearly all sprites appear to follow a positive lightning strike, a positive lightning strike doesn't guarantee a sprite will appear. Something else is evidently needed.

"Gravity waves may play a role in creating conditions suitable for them," says Hummel. A gravity wave in the air behaves like a ripple on a pond, with air rising and falling as it tries to balance out the forces of gravity and buoyancy. These waves are often seen around powerful thunderstorms, as the storm's strong updraft reaches the top of the troposphere, and that air is forced to spread outward. Research has already shown that the action of these gravity waves can have an impact on the upper atmosphere. This could be another way they influence what happens, far above the surface.

In the video below, recorded by Hummel in May of this year, gravity waves can clearly be seen radiating away from the storm, illuminated by a phenomenon called airglow. Amid the gravity waves streaming through the field of view, several sprites are also captured (watch closely at 1s, 3s, 7s and 12s into the video).

"I was extremely excited to see such clear evidence of both gravity waves and sprites in the timelapse," Hummel said.

Exactly how gravity waves could play a role in sprite formation isn't known. Some researchers have noted that sprites appear to form at what they call "plasma irregularities" in the ionosphere. However, these irregularities are themselves, also a mystery. Might gravity waves play a role in forming these irregularities? For now, no one knows. More sightings, more captures, and more research are required.

SIGHTINGS BECOMING MORE RARE

Sprites are wonderful to behold, and they are an important area of scientific research. They are not going away anytime soon. If storms become more powerful in our warming world, they could become more common. Sightings of them may decrease, however, due to the effects of light pollution.

As our cities expand outward, they bring urban lighting deeper into areas that were once dark rural regions. As a result, it is becoming more challenging to spot faint objects and occurrences in the sky. This is often mentioned in connection with astronomical events, such as meteor showers. Still, it is also affecting the observation and recording of sprites and other transient luminous events.

"Adopting better lighting practices can help us see and study more of these rare events," Hummel said.

Sources: Stephen Hummel/McDonald Observatory | ZT Research | NASA Earth Observatory | PSU | NWS |