The Great Lakes are at record warmth. Here's what that means for snow squalls

Cold air and relatively warmer lake waters are a prime setup for lake-effect snow squalls. Here's what forecasters expect in the coming weeks.

Drivers in southwestern Ontario's traditional snow belts were plunged into an early burst of winter-like weather last week, courtesy of lake-effect snow squalls.

PHOTOS: Days of lake-effect snow bring wintry feel to Ontario

Such squalls aren't uncommon in the fall and early winter months, and they rely on a few factors.

First: it helps if the lakes in question are still largely unfrozen. That matters because the lakes lose their warmth faster than the land, so when cold air moves in, it encounters lake waters markedly warmer than the air.

So when cold winds blow over the still relatively warm lakes, the moisture precipitates as snow, and is blown inland by those same winds. Depending on the direction, the further those winds have to travel over the lake surface, the more opportunity it has for that moisture to precipitate, and the more potent the eventual squalls (a process meteorologists call "fetch").

As we mentioned, the genesis of all this is still-warm, unfrozen lake water. And the Great Lakes have this in abundance this year. In fact, the lakes are at record-warm levels.

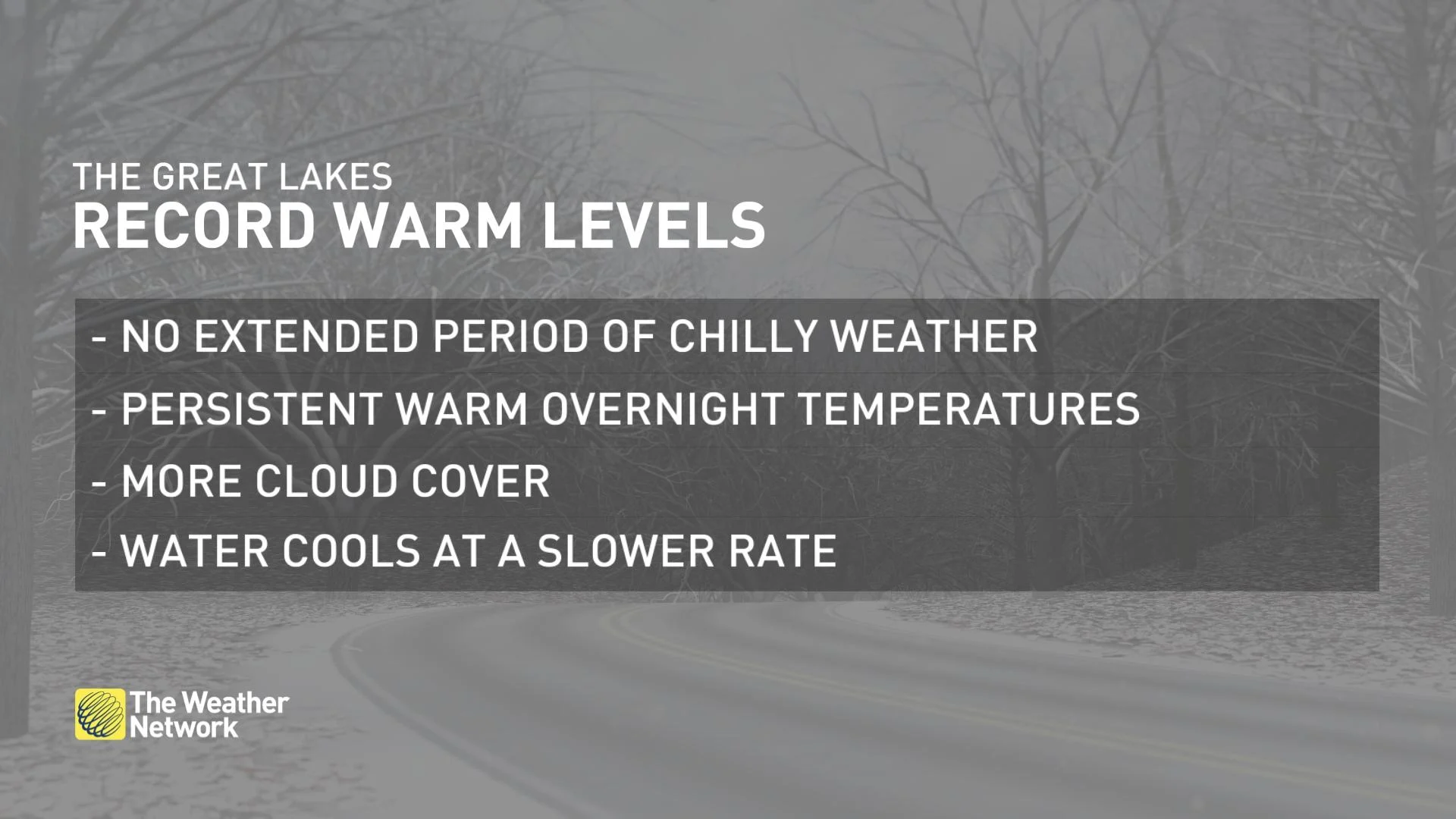

Why is this? This week's cold snap notwithstanding, there hasn't really been an extended period of chilly weather across Ontario, with long stretches of relatively mild overnight lows.

There's also been above-average cloud cover, which works to trap heat in the region – all of which limits the cooling of lake waters which, remember, already retain their heat for longer than the land.

So, the lakes are warm, and it'll be a good long while before they cool down and freeze, if they freeze at all. For people who don't prefer their commutes with a hefty dose of snow, that bodes ill for the coming weeks.

Forecasters say the late November pattern will mark the arrival of Arctic air, funnelled downward into Ontario by a building ridge of high pressure across the west.

Cold air over the warmer Great Lakes makes for a prime lake-effect snow setup – but that doesn't necessarily guarantee epic snow amounts for specific areas.

While the pattern and lake temperatures definitely boost the potential for lake-effect snow, there are other factors to consider, chief among them wind direction.

To really max out that squall potential, we need a favourable wind (out of the northwest, for instance), blowing for a good long way across the lake to grab onto more moisture (the "fetch" we talked about up above).

Second, for really heavy local amounts, the resulting bands of snow would need to lock in place, directing the snow over localized areas for prolonged periods of time. Too much meandering, and while more people might get those flakes, overall local amounts will be lessened. Areas far from Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, like the Greater Toronto Area, are very unlikely to get any epic snow blasts from this setup.

Another upside: Those warm lakes also serve a second purpose: they'll act as a moderating force on the same Arctic air that will be boosting lake-effect snow risk, taking the edge off the chill. In fact, the temperature setup may even be such that it will be lake-effect showers that manifest as we near the end of November.

Still, this whole setup is something to consider as Ontarians mull when to finally get their winter tires on.

With files from meteorologist Jessie Uppal.