First Black weather officers joined a segregated U.S. Air Force in WWII

The Tuskegee weathermen were behind the Tuskegee Airmen's historic run of missions.

This Day In Weather History is a daily podcast by Chris Mei from The Weather Network, featuring stories about people, communities and events and how weather impacted them.

--

On Monday, July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, colour, religion or national origin" in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of the U.S. military’s first Black pilots who fought in the Second World War. They were trained at the Tuskegee Institute, located near Tuskegee, Ala. These men fought in the segregated army air forces (now called the U.S. air force). So, with the first Black air force pilots came the first Black weather officers, dubbed the Tuskegee weathermen.

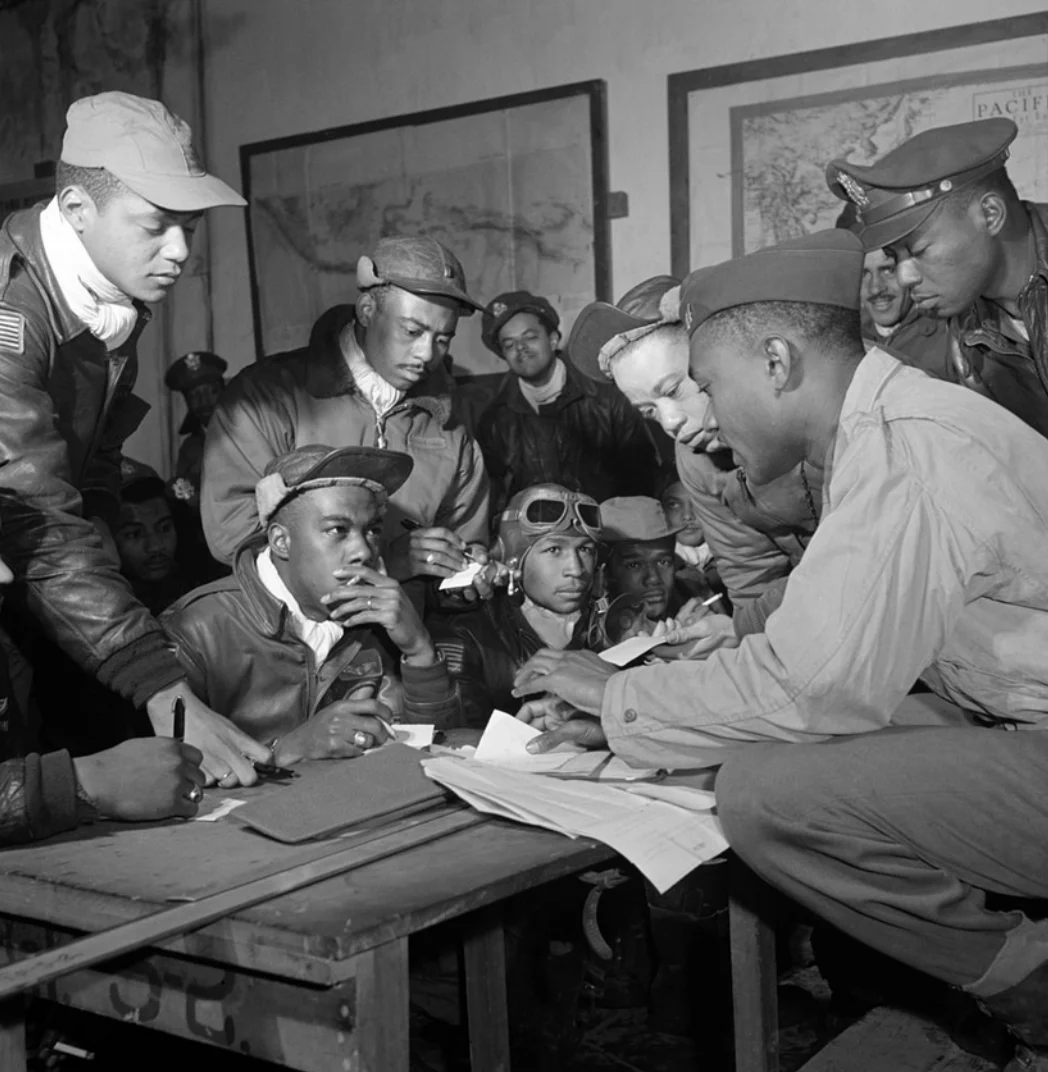

"Members of the 332nd Fighter Group in a mission briefing, Ramitelli, Italy, 1945." Courtesy of Toni Frissell Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (LC-USZC4-4335)

But it wasn't so easy to just enlist the leading Black meteorologists because, at the time, there weren't any in the U.S. Weather Bureau.

The army recruited black men who had a background in science and trained them in meteorology.

Charles E. Anderson, who studied chemistry in college, was accepted to the army air forces. He wanted to fly, but his eyesight was too poor.

Archie Williams also wanted to be a pilot in the army air forces, considering he already knew how to fly a plane.

Williams was in great shape, winning the gold medal during the 400-metre event in the 1936 Olympics. But, at 27, he was too old for military flight training. So, Williams worked on weather forecasts, weather maps, and even taught intro to flying.

There were 14 Tuskegee meteorologists, about 0.2 per cent of all weather officers in the army air forces.

Black pilots were also few in numbers and were regarded with suspicion.

The Tuskegee Airmen and weathermen were a great team, which is evidenced by the results of their missions.

"Members of the 332nd Fighter Group preparing for a mission, Ramitelli, Italy, 1945." Courtesy of Toni Frissell Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (LC-DIG-ppmsca-13259)

Air force historian Dan Haulman said, “Of the 179 bomber escort missions, they lost bombers to enemy aircraft on only seven of those missions,” adding that in total, they lost 27 bombers, while other groups lost 46 bombers on average.

Haulman said that “Just as the black pilots proved that they could fly military aircraft in combat as well as the white pilots, so did the black weather personnel prove that they could perform meteorological functions as well as the white officers."

The Tuskegee Airmen helped change the attitudes of their white counterparts. Williams saw this change occur, because at the beginning "...a lot of guys there were bigoted. The white guys didn’t want to fly with them and all, but they found out that these guys could fight, could shoot good and protect the bombers.”

Memorial honouring the Tuskegee Airmen at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Tuskegee, Ala. Courtesy of Staff Sgt. Christine Jones/U.S. Air Force

The Tuskegee weathermen had the same positive and progressive influence due to their success in weather forecasting.

To hear more about The Tuskegee weathermen, listen to today's episode of "This Day In Weather History."

Subscribe to 'This Day in Weather History': Apple Podcasts | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | Spotify | Google Podcasts | iHeartRadio | Overcast'

Thumbnail image: Members of the 332nd Fighter Group, Ramitelli, Italy, in 1945. Courtesy of U.S. air force.