Violent tornadoes are sorely undercounted, study shows

Studies like this one are part of the solution that aims to help re-work the archaic tornado rating systems and help establish a more comprehensive and accurate one into the future.

A recent research paper highlights that strong, violent tornadoes might not be as rare as first imagined.

Researchers at the University of Illinois understood most tornadoes occurred in rural settings and that an official damage survey generally low-balls true tornado intensity, but the exact discrepancy might be far larger than first initially thought.

Like a scene out of the movie Twister, an advanced mobile radar, the Doppler On Wheels (DOW), is literally driven into adverse and dangerous thunderstorms by scientists – in the hopes to sample the strongest winds of a tornado.

SEE ALSO: Canada saw 77 tornadoes in 2020, Ontario set new record

The high-resolution, mobile doppler units have a drawback. You have to get close: Sometimes less than one kilometre from the dangerous tornado. For some scientists and storm chasers alike, that’s a dream.

The DOW effectively sampled dozens of supercell tornadoes across the U.S. Plains between 1995 and 2006, and the results show that most tornadoes are much stronger than the National Weather Survey (NWS) damage surveys. Moreover, 20 per cent of the DOW sampled tornadoes capable of causing EF-4/EF-5-level damage.

The previous damage surveys from the NWS indicate that just 1 per cent are rated an EF-4/EF-5.

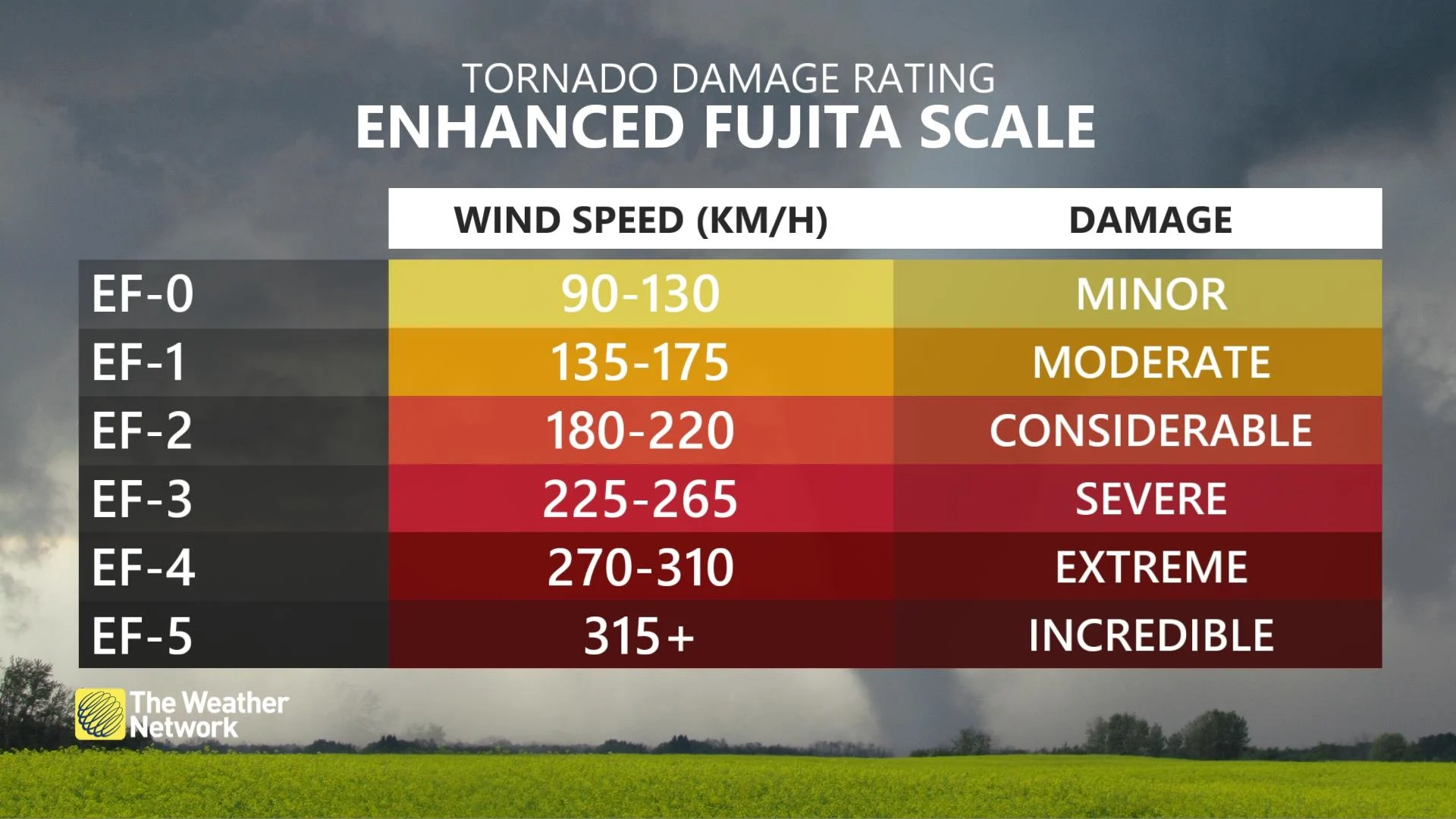

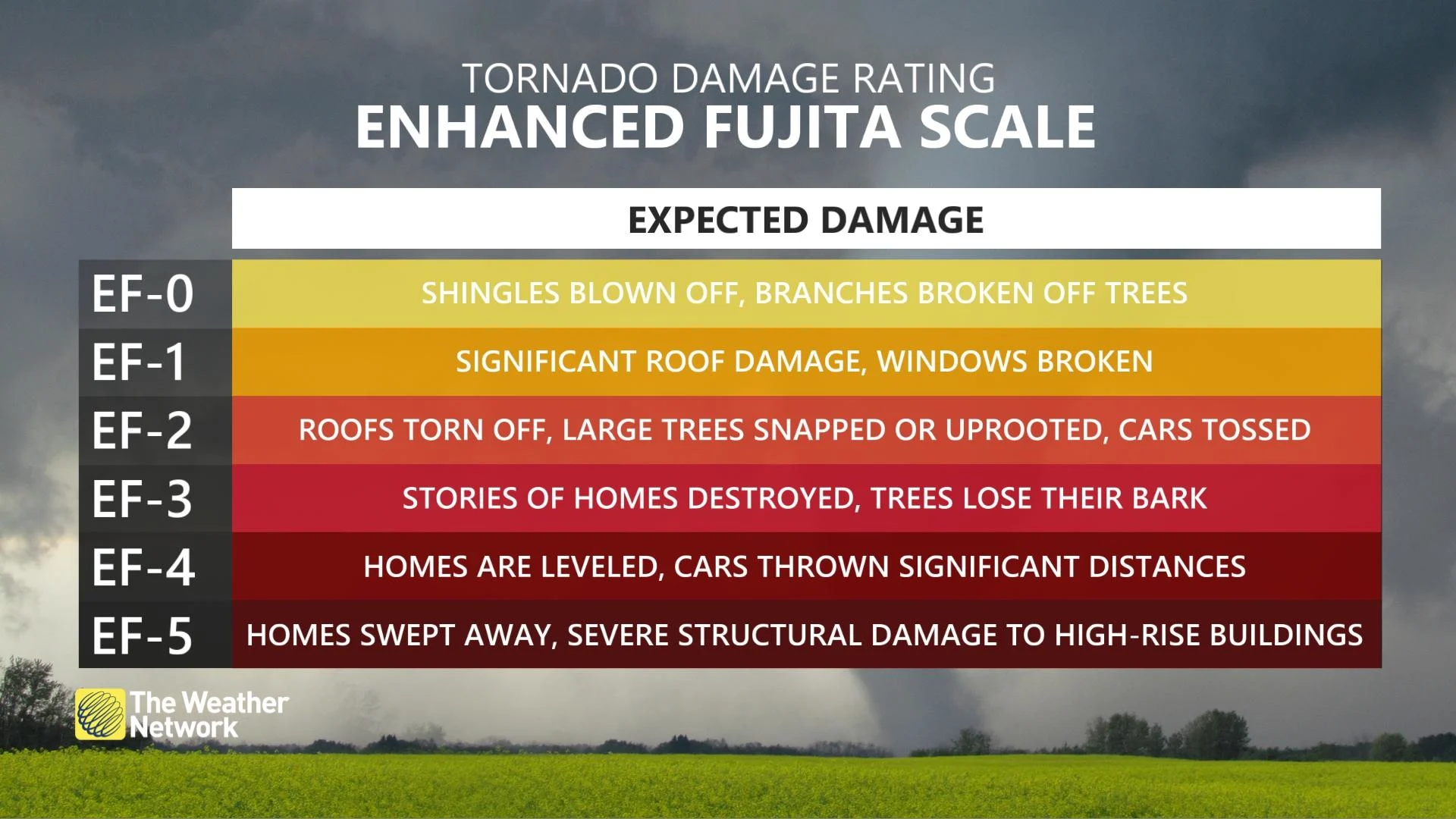

What do these somewhat abstract letters and numbers represent?

It’s the Enhanced Fujita scale, specifically for tornado intensity. The big drawback is that it’s entirely reliant on tornado damage, so it’s a wind estimate, not a true measurement. It’s been found that the more damage and evidence a tornado leaves behind, the more accurate the applied rating is by the National Weather Service.

Take a typical school building, for an example: An EF-0/EF-1 tornado is capable of breaking the windows, while an EF-4/EF-5 is capable of destroying a large portion (or all) of the structure.

This recent research uncovered that on average, the National Weather Service classified tornadoes 1.2-1.5 categories lower than what the DOW uncovered through direct sampling – highlighting the chronic underestimation of the true power of tornadoes.

The difference between the DOW and NWS-rated wind speed for 82 tornadoes in the study is strikingly high, at 72 km/h.

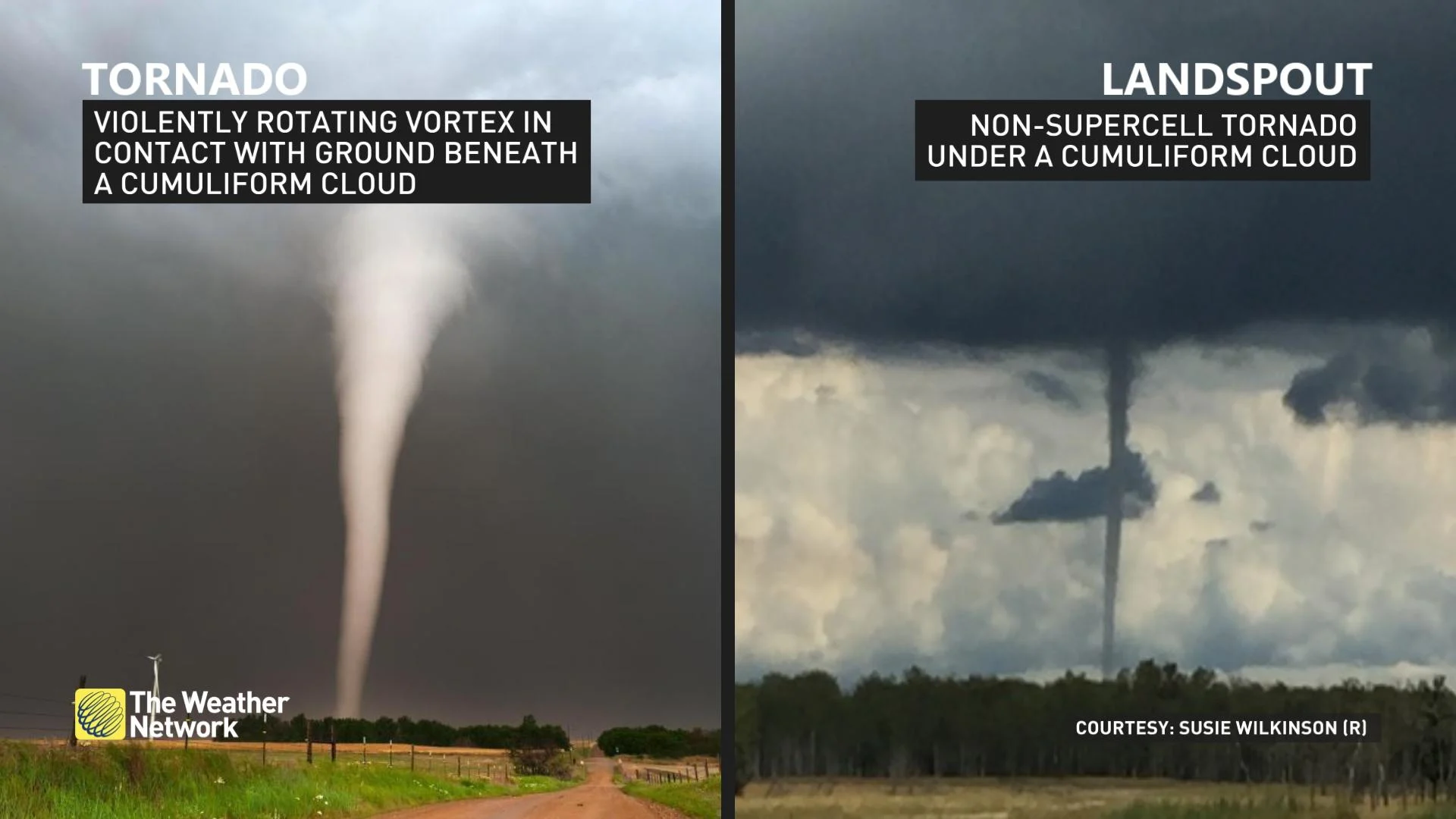

Of course, like most studies, this one has limitations such as sampling bias, occurring exclusively in the Plains region of the United States. The paper also focused on supercell tornadic activity while excluding quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS) and non-supercell tornadoes, most of which are generally weaker and shorter-lived tornadic events.

It's also important to highlight that the DOW was used during setups where atmospheric parameters were conducive to the development of thunderstorms capable of producing violent tornadoes.

Another unique correlation uncovered in the study: There doesn't appear to be a correlation between tornado width and intensity. Wider tornadoes have the propensity to strike more infrastructure and are a better conduit to loft potentially debris into the air.

There are some ramifications that the NWS-ratings system is consistently low-balling tornado width and intensity.

Strong tornadoes can cause irrevocable harm to people when violent winds impact structures and communities. It's paramount that tornado hazards are appropriately scrutinized and re-worked, helping to convey the risk of encountering violent tornadoes to the myriad of appropriate stakeholders.

Studies like this one are part of the solution that aims to help re-work the archaic tornado rating systems and help establish a more comprehensive and accurate one into the future.