What it's like to chase the storms that spawned five tornadoes in Ontario

Weather Network Storm Hunter Mark Robinson shares his experiences of the June 10 storms that spawned five confirmed tornadoes in southern Ontario.

The shelf cloud that stretched from horizon to horizon didn’t look to be moving all that fast towards where I stood on the cliff in Goderich, but I’d been fooled before.

These storms had a habit of looking spectacular and dangerous, but tended not to have major impacts on the communities that they roared over. Shelf clouds are, more often than not, an indication of a linear storm system that doesn’t usually spawn the far more dangerous, rotating storms we call supercells.

So as I stood there in Goderich marvelling at the magnificent structure of the storm that was sweeping towards me, tornadoes were not foremost in my mind.

What I didn’t know was that this shelf was the seed of a destructive outbreak of tornadoes in Ontario that would stretch from Huntsville to west of London.

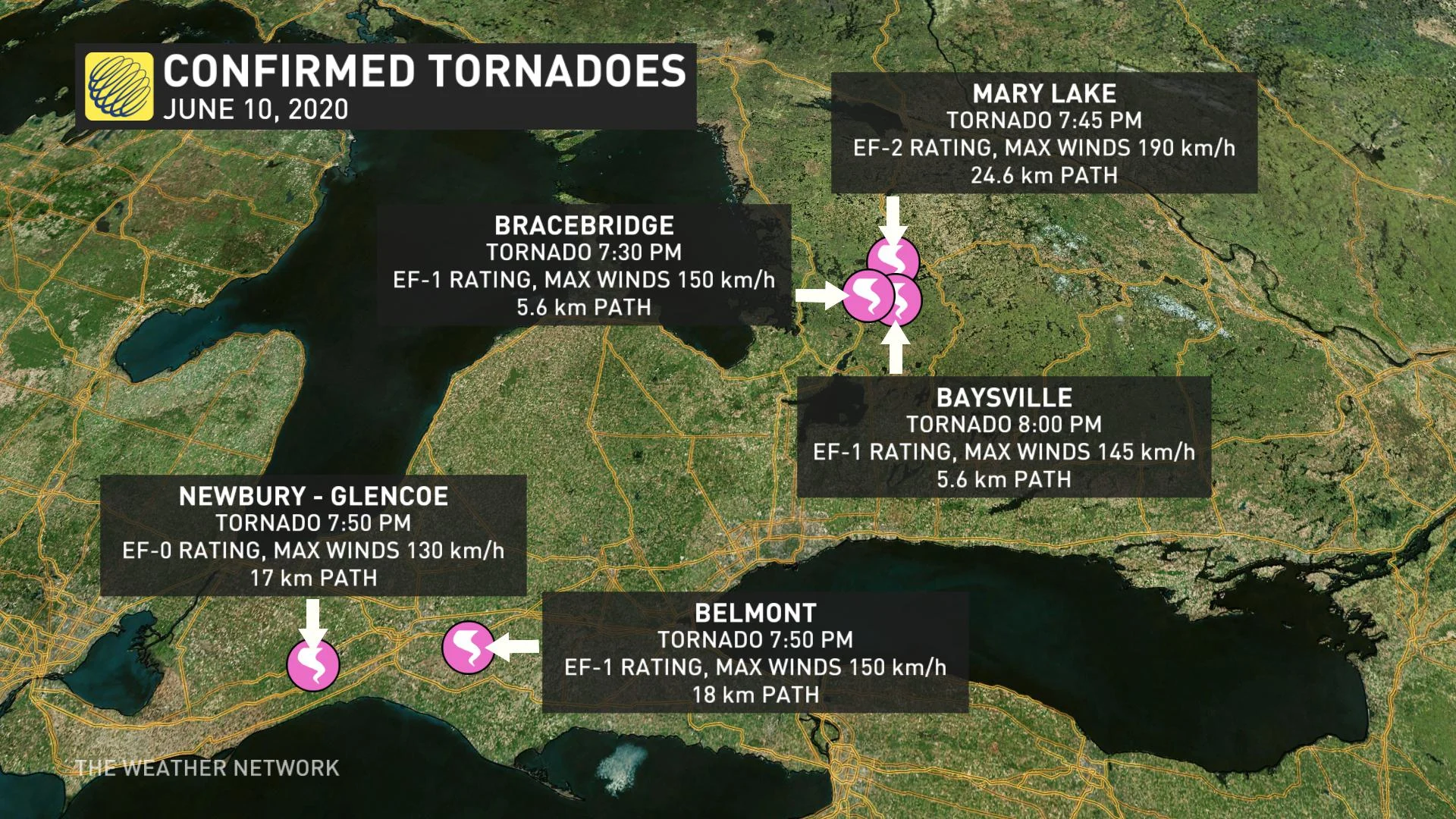

The storm system has now been confirmed by the Northern Tornadoes Project (a partnership between Western University and ImpactWx) to have spawned five tornadoes, two near London, and now three more in Bracebridge (EF-1), Baysville (EF-1), and Mary Lake near Huntsville (EF-2).

The storm system that swept into Southern Ontario on June 10 was part of a larger system of tropical moisture that combined the remnants of Tropical Storm Cristobal along with a sharp trough in the jetstream (a critical component in producing severe thunderstorms).

Pursuing active weather that day was an exercise in tough choices. The atmospheric conditions looked good for possible tornadoes in the Hunstville area, but the lack of roads and the abundance of trees meant that capturing anything on camera was unlikely and dangerous. Tornadoes were less likely to the southwest near London, but that area features a good road network and fewer trees. So, I split the difference and settled on Goderich.

When I arrived in the town, I could already see the edge of the cirrus cloud deck created by the storms as they congealed into a massive line stretching from northern Michigan all the way down to Kentucky. I knew the motion of the line as going to be quick, but what I didn’t anticipate was how fast it was really going to be.

As the line swept over me, it was already moving east at about 100 km/h, very fast for a system like this. I turned the car east, trying to get ahead of the fierce winds and rain in the storms, and to try and keep up with the edge of what we now called a QLCS – a Quasi Linear Convective System. This a very fancy phrase for a line of storms which, in this case, stretched from northeast to southwest. This storm system latched onto the very warm, very humid airmass that the remnants of Tropical Storm Cristobal brought to Ontario, and fed upon the rich fuel it provided.

Image: Mark Robinson.

As I raced southeast trying to keep up, I noticed something odd; the storms that were pursuing us began to fall apart. Lightning slowed, then stopped, the structure of the shelf collapsed until there was only a hint of the edge of the cold air spewed out by the dying shelf continuing south.

On radar, the northern storms were racing along with barely a change in their strength and they were heading right into the conditions that would help create enough spin in them to create the three tornadoes that would strike Baysville, Bracebridge, and Mary’s Lake.

The edge of the cold air racing south above me (known as an outflow boundary) would go on to interact with another line of storms coming into Ontario from Michigan and produce two long-tracked tornadoes in Belmont (south of London) and Glencoe.

As fast I dropped south, the outflow boundary dropped faster and produced the tornadoes just out of my reach. But I did manage to run right through the storm that produced the Glencoe tornado just after it lifted. I ended the day in a mess of rain, lightning and wind and, while awesome, it still wasn't quite as good as witnessing the tornado that happened just to my west behind the massive all of wind and rain.

As I write this, it looks like all the tornadoes are what we call “gustnadoes,” or tornadic vortices associated with the leading edge of the gust front (which also creates the shelf cloud that’s often so dramatic). These tornadoes tend not to be as powerful as those created by a mesocyclone (the core of a spinning supercell), but can still do considerable damage.

The Mary’s Lake tornado had a near 25-kilometre damage path with a max width of 540 m and likely wind speeds close to 190 km/h; an EF-2.

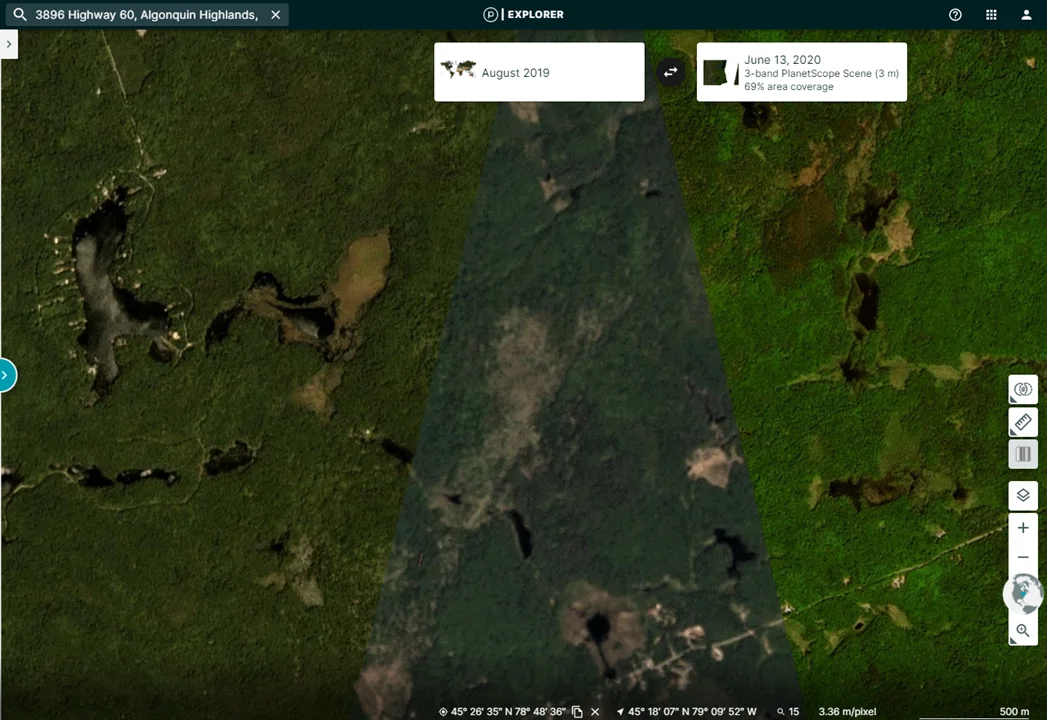

Lighter forest areas in the highlighted cone in the image above show the damage to trees from the Mary's Lake tornado. Image: Planet.com

This kind of outbreak is not unusual in Ontario and I’ve been witness to one storm that produced 13 gustnadoes on Lake Huron (including a weak one that ran right over me), but this may be the only outbreak that was associated with the remnants of a tropical storm this early in the season.

Will we see more this year? The answer is we don't know, but as we are coming into our most active period for summer severe weather in Ontario, I know that I’m likely to be busy this year.