A super-rare Perigee Blue Moon lights up the night sky this summer

This year's famed Perseid meteor shower promises to be exceptionally good as well!

With warm nights during the summer months, this is just about the best time of year to stay up late and gaze up into the heavens.

Watch for some of the brightest planets to be visible during the summer months, but the 'stars' of the season will be in August, with the Perseid meteor shower and the Perigee Blue Moon lighting up our night skies.

Here is our guide to the astronomical sights on display for Summer 2023:

Jun 21: Summer solstice (northern hemisphere)

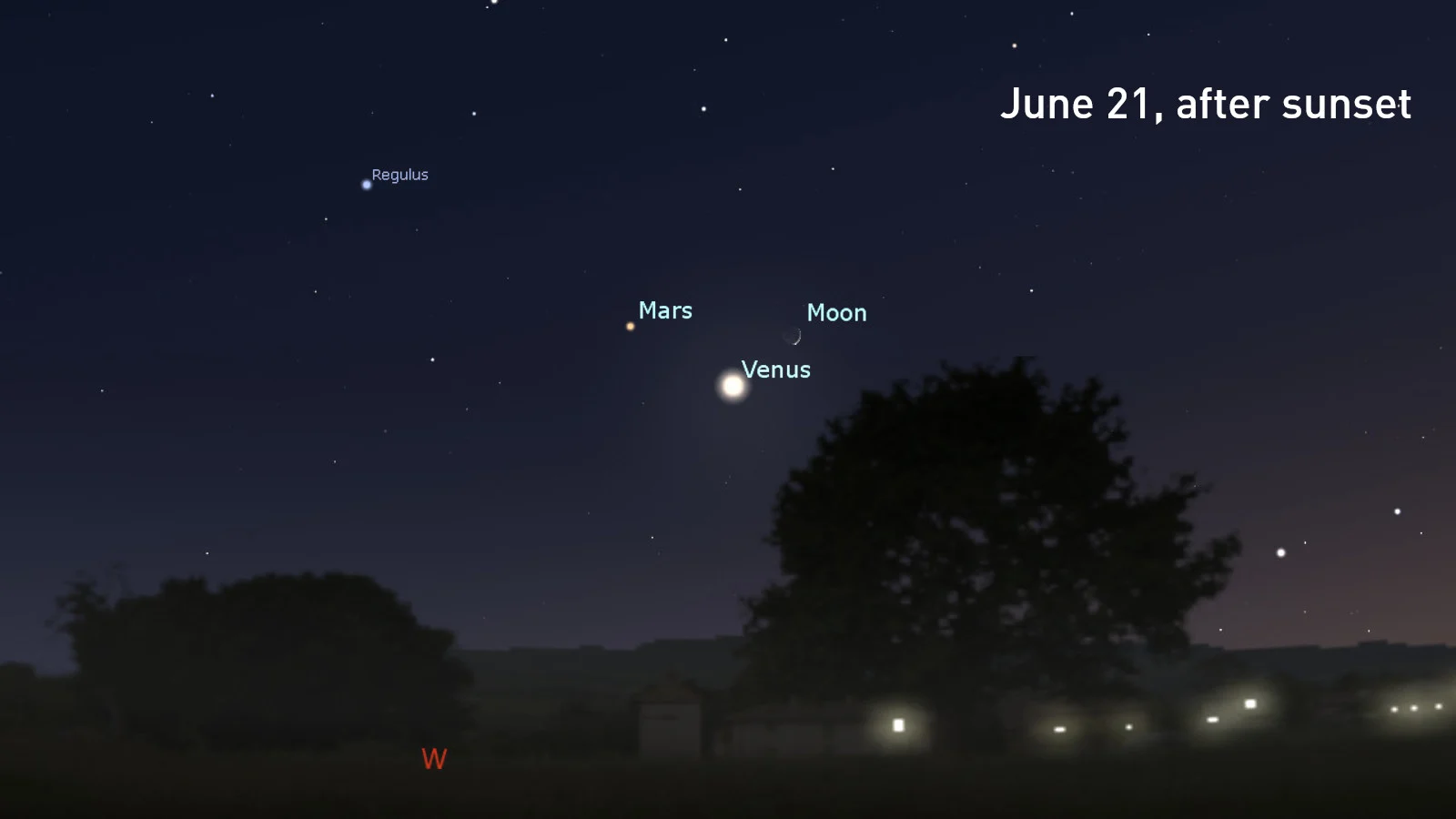

Jun 21: Venus, Mars & Crescent Moon form triangle in the west post-sunset

Jul 1: Venus & Mars at their closest

Jul 3: Super Buck Moon

Jul 6: Earth at aphelion (farthest point from the Sun for 2023)

Jul 7: Venus at its brightest for the next week

Jul 12: Jupiter close to the Crescent Moon, predawn

Jul 12: southern delta Aquariid meteor shower begins (ends Aug 23)

Jul 17: Perseid meteor shower begins (ends Aug 24)

Jul 17: New Moon

Jul 29-30: southern delta Aquariid meteor shower peaks

Aug 1: Super Sturgeon Moon

Aug 12-13: Perseid meteor shower peak

Aug 16: Apogee New Moon (farthest New Moon of 2023)

Aug 18: Mars near thin Crescent Moon

Aug 27: Saturn at Opposition

Aug 31: Perigee Blue Moon (Closest Full Moon of 2023 & 2nd Full Moon of August)

Sep 1: Zodiacal Light visible in the east before morning twilight for 2 weeks

Sep 4: Gibbous Moon passes by Jupiter

Sep 15: New Moon

Sep 16: Crescent Moon occults Mars

Sept 19: Venus at its brightest again for the next week

Sep 22: Mercury highest in eastern sky, predawn

Sep 23: Autumn Equinox (northern hemisphere)

Visit our Complete Guide to Summer 2023 for an in-depth look at the Summer Forecast, tips to plan for it, and much more!

The Planets

Venus has been exceptionally bright in the western sky after sunset for much of Spring, and this will continue into Summer. Look for the 'evening star' to emerge from the Sun's glare each evening. The planet Mars will be nearby each night as well.

Venus, Mars and the Crescent Moon form a triangle in the evening sky on June 21, 2023. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Watch for a thin Crescent Moon to hang near the pair on the first night of Summer. During the week and a half afterward, Venus and Mars will draw closer together, reaching their closest distance in our sky on the night of July 1.

These two will continue to track closer and closer to the horizon each night following, until they are lost in twilight in the latter half of July.

Over in the east, to start the season, look for Saturn to rise after midnight, with Jupiter following along about two hours later. Throughout the season, these two planets will rise earlier and earlier, and thus will be easier to observe.

Saturn, the Crescent Moon, and Jupiter line up in the night sky in the pre-dawn hours of July 9. Credit: Stellarium

By the beginning of August, Saturn will be up in the hours just after sunset, with Jupiter rising around midnight. On August 27, Saturn will reach Opposition, and will be up all night long, lined up on exactly the opposite side of Earth from the Sun. Jupiter will still be lagging behind, rising closer to 11 p.m., but as we transition into September, this trend of rising earlier continues, making them easier to see for the casual skywatcher.

Of particular note is one last event that is specifically for anyone who has access to a telescope or binoculars. In the daytime hours of September 16, the planet Mars will pass directly behind the Crescent Moon. Given that the Sun will be shining brightly in the sky at the time, this will be difficult to observe, but it could be a very rewarding event to witness!

Meteor showers

Each year in July and August, as Earth continues on its orbit around the Sun, the planet passes through two overlapping streams of comet debris in space. When this happens, the bits of ice, dust, and gravel in the streams cause meteors to streak across our night skies.

The southern delta Aquariids

We encounter the first of these two streams starting around July 12. Thought to originate from a comet named 96P/Machholz, the debris in this stream produces a meteor shower known as the southern delta Aquariids.

This meteor shower begins with only a one or two meteors per hour, visible starting around 10:30 p.m. each night as the radiant rises in the east, but best viewed in the hours after midnight when the radiant is directly to the south. The number of meteors roughly doubles each night in the last few days of the month, reaching around 20 per hour during the shower's peak on the nights of July 29 and July 30.

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower gets its name from the fact that its radiant is near the constellation Aquarius. This view of the night sky shows the radiant's location in the predawn sky on July 29, 2022. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Although not a particularly strong shower, southern delta Aquariids meteors tend to be fairly bright.

In 2023, the timing of this meteor shower isn't ideal. It peaks just before the August 1 Full Moon. So, with the bright light in the sky on the two nights of the peak, it will reduce the number of meteors the average viewer will see.

The Perseids

The location of the Perseids radiant in the northeast, at midnight on August 12-13. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Earth plunges into the second of the two debris streams on July 17. Left behind by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, the meteoroids from this stream put on one of the best meteor displays in the northern hemisphere — the Perseid meteor shower.

The Perseids have the distinction of being the meteor shower with the greatest number of 'fireball' meteors. Fireballs are meteors that are so bright they can outshine the planet Venus, and they are easily visible through any light pollution from the Moon or even cities.

Watch: Perseid fireball captured on camera

Although the Perseids start off fairly quiet for the first two weeks or so, the number of meteors quickly ramps up in early August. During the peak — on the night of August 12-13 — the shower can deliver up to 100 meteors per hour. Sometimes even more!

The Perseids radiant — the position the meteors appear to originate from in the sky — is a special one. Positioned in the northeastern sky, it never sets below the horizon at this time of year. So, there's no waiting for this meteor radiant to rise. Observers need only wait for the Sun to completely set.

2023 may be one of the best years for seeing the Perseids, due to the timing of the shower with respect to the phases of the Moon.

With the peak occurring just a couple of days before the New Moon, there will only be a thin Crescent Moon in the sky to start off the night. So, this will give us a nice dark sky for the rest of the night for meteor spotting.

Read on for tips on how to get the most out of viewing a meteor shower.

DON'T MISS: Wow. Weird 'rock comet' 3200 Phaethon is way stranger than we thought!

The Perigee Blue Moon

At the end of August, we will witness a rare event in the night sky — a Perigee Blue Moon.

This image of the August 31 Perigee Blue Moon is a composite from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit: NASA's Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio/Scott Sutherland

Now, there are two definitions for a Blue Moon. The first is "the third Full Moon in a season with four Full Moons." The second is "the second Full Moon in a calendar month."

The reasons for this are somewhat complicated, but in both cases, they describe an 'extra' Full Moon. The 'seasonal' definition made more sense over a century ago, when farmer's almanacs tracked years solely based on the seasons, with the winter solstice marking the transition from one year to the next. However, in our modern calendar, years with a seasonal Blue Moon have only 12 Full Moons in total. It's the years with a calendar Blue Moon that end up having an extra 13th Full Moon.

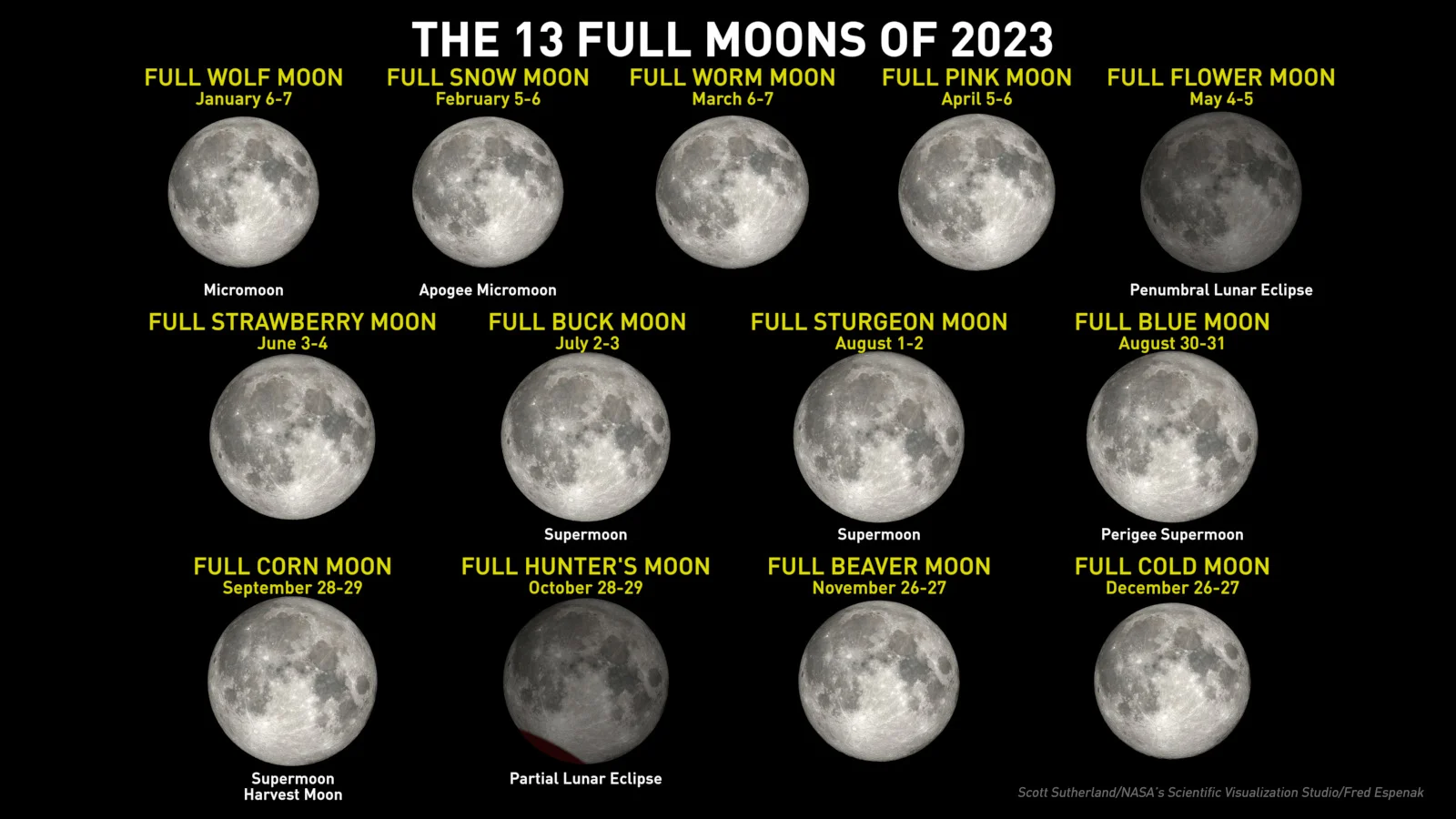

The 13 Full Moons of 2023, including their popular names and any other notable facts — supermoons, micromoons, lunar eclipses, etc. Credit: Scott Sutherland/NASA GSFC, with data from Fred Espenak.

With the 13 Full Moons of 2023, the 'extra' one falls on August 31. Since we assign each Full Moon of the year a different name based on what month it occurs in, as shown above, this extra Full Moon is simply called the Blue Moon.

There's something extra special about this 'extra' Full Moon, though. It will also be the closest, biggest, and brightest Full Moon of 2023!

The term 'supermoon' is quite popular these days. These are Full Moons that appear larger and brighter because they occur when the Moon is near its closest approach to Earth in that particular orbit. There are between three and five supermoons every year. Among those there will be one that is closest of them all. This is the Perigee Moon.

In 2023, we have four supermoons — July 3, August 1, August 31, and September 29. As coincidence would have it, the August 31 Blue Moon is also 2023's Perigee Moon.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio/Scott Sutherland

While there's a Perigee Moon every year, and a calendar Blue Moon every three years or so, Perigee Blue Moons are surprisingly rare!

The last time we saw one of these was on July 30, 1996.

While there have been plenty of Blue Moons and even Super Blue Moons since, August 31 is the first Perigee Blue Moon in roughly 27 years.

However, after this, we'll apparently have to wait even longer. According to retired NASA scientist Fred Espenak, there's no shortage of Blue Moons or Super Blue Moons to come, but the next Perigee Blue Moon doesn't occur until December 31, 2115, over 92 years from now!

The Zodiacal Light

Have you ever been out in the hours just after sunset or before sunrise and noticed a bright pyramid of light covering a significant portion of the sky? If so, you may have seen an elusive phenomenon known as the Zodiacal Light.

For about two weeks starting on September 1, turn your gaze to the eastern horizon in the half hour before morning twilight. Specifically, you are looking for a diffuse white glow in the shape of a pyramid, with its base along the horizon and peak extending high into the sky. If you miss it during those dates, the phenomenon is visible again, at the same time of the morning, between October 23 and November 6.

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: European Southern Observatory (ESO)

The zodiacal light is produced by sunlight glinting off grains of dust that float in an immense disk surrounding the Sun. However, we can only see this effect at specific times of the year. In February and March, it appears in the western sky, in the half-hour after evening twilight, in the two weeks just after the Full Moon. In September and October, we can see it in the eastern sky, in the half-hour or so before morning twilight, during the two weeks following the New Moon.

New research has shed fresh light on this phenomenon. It was once thought that the dust cloud that produces the zodiacal light originated from comet tails. However, researchers used data from NASA's Juno spacecraft to reveal it may actually be Martian dust floating in space!

The best way to be sure that you really are seeing this phenomenon is to look up the exact timing of twilight in your area so that you know precisely when it begins, and get away from city lights so that you are sure light pollution isn't going to spoil the view.

Tips for watching a meteor shower

Meteor showers are events that nearly everyone can watch. No special equipment is required. In fact, binoculars and telescopes make it harder to see meteor showers, by restricting your field of view. However, there are a few things to keep in mind so you don't miss out on these amazing events.

The three best practices for observing the night sky are:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Clear skies are essential. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin your chances of watching an event such as a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. If you look up into the sky from home, what do you see? The Moon, a planet or two, perhaps a few bright stars such as Vega, Betelgeuse and Procyon, as well as some passing airliners? If so, there's too much light pollution in your area to get the most out of a meteor shower. You might catch an exceptionally bright fireball if one happens to fly past overhead, but that's likely all you'll see. So, to get the most out of your stargazing and meteor watching, get out of the city. The farther away you can get, the better.

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village until a multitude of stars is visible above your head.

In some areas, especially in southern Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over. The best options for getting away from light depend on your location. In southwestern Ontario and the Niagara Peninsula, the shores of Lake Erie can offer some excellent views. In the GTA and farther east, drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

If you can't get away, the suburbs can offer at least a slightly better view of the night sky. Here, the key is to limit the amount of direct light in your field of view. Dark backyards, sheltered from street lights by surrounding houses and trees, are your best haven. The video above provides a good example of viewing based on the concentration of light pollution in the sky. Also, check for dark sky preserves in your area.

When viewing a meteor shower, be mindful of the phase of the Moon. Meteor showers are typically at their best when viewed during the New Moon or Crescent Moon. However, a Gibbous or Full Moon can be bright enough to wash out all but the brightest meteors. Since we can't get away from the Moon, the best option is just to time your outing right, so the Moon has already set or is low in the sky. Also, you can angle your field of view to keep the Moon out of your direct line of sight. This will reduce its impact on your night vision and allow you to spot more meteors.

Once you've verified you have clear skies and you've limited your exposure to light pollution, this is where being patient comes in.

For best viewing, your eyes need some time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but 30-45 minutes is best for your eyes to adjust from being exposed to bright light.

Note that this, likely more than anything else, is the one thing that causes the most disappointment when it comes to watching a meteor shower.

If you step out into your backyard from a brightly lit home and looking up for a few minutes, you might be lucky enough to catch a rare bright fireball meteor. However, it's far more likely that you won't see anything at all. Meteors may be streaking overhead, but it takes time for our eyes to adjust, so that we can actually pick out those brief flashes of light. Waiting for at least twenty minutes, while avoiding sources of light during that time (streetlights, car headlights and interior lights, and smartphone and tablet screens) dramatically improves your chances of avoiding disappointment.

Sometimes, avoiding your smartphone or tablet isn't an option. In this case, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off and reduce the screen's brightness. That way, it will have less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly gaze into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few of the brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark.

Once you're all set, just look straight up and enjoy the view!

--

(Thumbnail image courtesy NASA's Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio)