Blue Moon, lunar eclipse, fireballs: Your summer stargazing guide is here

Perseid fireballs, a Blue Moon, and a lunar eclipse, all in the same season! What more could we ask for?

Summer is an excellent time to stay up late and stargaze, with plenty to see in the night sky, including one of the best meteor showers of the year.

Watch for some of the brightest planets to be visible in the predawn and evening skies during the summer months. The real 'stars' of the season will be the Perseid meteor shower and the Seasonal Blue Moon, which will both light up our night skies in August. Plus, we cap the season off with a Super Harvest Moon Partial Lunar Eclipse!

Here is our guide to the astronomical sights on display for Summer 2023:

Jun 20: Summer solstice (northern hemisphere)

Jun 20: 'Planet Parade' alignment in the predawn sky

Jun 21-22: Full Strawberry Moon

Jun 27-July 4: Moon passes by the 'Planet Parade'

Jul 5: Earth at aphelion

Jul 7: Mercury near thin Waxing Crescent Moon

Jul 12: Southern Delta Aquariid meteor shower begins

Jul 17: Perseid meteor shower begins

Jul 20-21: Full Buck Moon

Jul 23 & 24: Waning Gibbous Moon near Saturn

Jul 31 & Aug 1: Southern Delta Aquariids peak

Aug 12-13: Perseids peak

Aug 19-20: Super Blue Sturgeon Moon

Aug 23: Southern Delta Aquariids end

Aug 24: Perseids end

Sep 1: Zodiacal Light in the east before morning twilight for 2 weeks

Sep 5: Mercury highest in predawn eastern sky, Waxing Crescent Moon near Venus

Sep 8: Saturn Opposition

Sep 10: Waxing Crescent Moon near Antares

Sep 17: Waxing Gibbous Moon near Saturn

Sep 17-18: Super Harvest Moon Partial Lunar Eclipse

Sep 22: Autumnal Equinox (northern hemisphere)

Visit our Complete Guide to Summer 2024 for an in-depth look at the Summer Forecast, tips to plan for it, and much more!

Summer Solstice

At 4:51 p.m. EDT on June 20, 2024, the Sun will reach its highest point in the sky in the northern hemisphere for this year.

This 'pause' in the position of the Sun in the sky will mark the start of northern Summer and southern Winter for 2024.

This solargraph image records the path of the Sun across the sky each day from summer solstice to winter solstice in 2023, interrupted only by cloudy skies. (Bret Culp)

With the change in the timing of the equinoxes and solstices, year by year, and with 2024 being a Leap Year, this summer solstice will be the earliest seen since 1796.

The Planets

You may have heard some hype in the media and on the internet about the "Rare Planet Parade" that was to occur on the morning of June 3. While that event was not the astronomical spectacle many were promising, there are many opportunities to see the planets throughout the summer months.

In the early mornings, before the first light of the Sun begins to peek over the horizon, look to the east for the true Planet Parade.

Jupiter, Uranus, Mars, Neptune, and Saturn will be lined up above the eastern horizon. Only Jupiter, Mars, and Saturn will be visible to the unaided eye. A telescope or a pair of powerful binoculars will be needed to see the other two.

Each morning from June 27 through July 4, the Moon will join the parade, passing by each planet in turn. June 29 will probably feature the best view, when the Crescent Moon will appear lined up with all of the planets.

Five planets and the Crescent Moon line up in the eastern sky on the morning of June 29, 2024. (Stellarium)

Those same five planets will remain visible in the sky each morning, rising earlier and earlier until, by the beginning of September, we'll be able to see them all above the horizon by midnight. (You'll still need a telescope or binoculars to see Uranus and Neptune, though.)

Meanwhile, Mercury and Venus will be 'hanging out' in the western sky just after sunset. They may be challenging to spot in the first couple of weeks of summer, as they'll still be a bit too close to the Sun. However, into early July, both will climb higher above the horizon, giving us a chance to see them emerge from evening twilight before they set for the night.

Mercury and the Moon just above the horizon after sunset on July 7, 2024. (Stellarium)

On the night of July 7, around 9:45 p.m., local time, look to the western sky. You may spy this small bright world hanging out with the thin Waxing Crescent Moon for a short bit before they both slip below the horizon. In the half hour or so before that, you may also spot Venus much closer to the horizon before Mercury emerges from the dimming twilight.

Both of these planets remain fairly shy throughout most of the season. Venus stays near the western horizon, becoming easier to see in August as it sets later and later. Mercury will peek up above the eastern horizon before sunrise around the end of August and the beginning of September.

On the morning of September 5, look for Mercury at its "greatest western elongation" or its highest point above the eastern horizon. Then, that same evening, watch for Venus near the western horizon, along with the Waxing Crescent Moon.

Aphelion 2024

On July 5, at exactly 1:06 a.m. EDT, our planet will reach the farthest distance from the Sun along our elliptical orbit for this year. This is known as aphelion (pronounced ah-FEEL-ee-uhn).

At that time, Earth will be around 152,099,970 km from the Sun, or just over 2.5 million km farther than its average distance of 149,597,870 km (1 'astronomical unit').

The point where Earth is closest to the Sun is called perihelion (perr-i-HEEL-ee-uhn). In 2024, it occurred on January 2, at 7:39 p.m. EST, when Earth was about 147,100,633 km from the Sun. During the next perihelion, on January 5, 2025, at 8:28 a.m. EST, Earth will be even closer than during perihelion 2024, at a distance of 144,648,083 km from the Sun.

Meteor showers

Every July and August, Earth passes through two overlapping streams of comet debris in space. As we traverse these streams, the bits of ice, dust, and gravel contained within them produce meteors streaking across our night skies.

The Southern delta Aquariids

We encounter the first of these two debris streams starting on July 12.

Potentially originating from a comet known as 96P/Machholz — an odd 'sun-grazer' that may be an alien visitor to our solar system — the dust and ice in this stream is responsible for our yearly Southern Delta Aquariid meteor shower.

For the first two weeks of the Southern Delta Aquariids, up until the 27th of July or so, observers typically see only about one or two meteors every hour. They start showing up between 10:30 and 11 p.m. each night, as the constellation Aquarius rises in the east, and can appear at any point in the sky from then until morning twilight.

The radiant of the Southern Delta Aquariid meteor shower, at roughly 1 a.m. local time, on the night of July 31-August 1, 2024. (Stellarium/Scott Sutherland)

However, after the 27th, the number of meteors roughly doubles each night until they reach around 20-25 per hour as the shower peaks on the nights of July 31 and August 1. After that, the numbers drop off again, but a few per hour can still be spotted each night until August 23.

Although not counted among the strongest showers of the year, Southern Delta Aquariid meteors still tend to be fairly bright.

In 2024, the timing of this meteor shower is quite good. The nights of the peak feature a thin Waxing Crescent Moon that only rises in the hours before morning twilight. Thus, provided we have clear skies, this is an excellent year to check out the Southern Delta Aquariids.

The Perseids

The location of the Perseids radiant in the northeast, at midnight on August 12-13, 2024. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Earth plunges into the second debris stream starting on July 17. Left behind by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, the meteoroids from this stream put on one of the best meteor displays in the northern hemisphere — the Perseid meteor shower.

Although the Perseids start off fairly quiet for the first two weeks or so, the number of meteors quickly ramps up in early August. During the peak — on the night of August 12-13 — the shower is capable of delivering up to 100 meteors per hour. Sometimes even more!

The Perseids also has the distinction of being the meteor shower with the greatest number of fireballs. A 'fireball' is any meteor that is at least as bright as the planet Venus, and they can be visible for hundreds of kilometres around, even during a Full Moon or from under severe urban light pollution.

Watch: Perseid fireball captured on camera

The Perseids radiant — the position the meteors appear to originate from in the sky — is a special one. Most meteor shower radiants rise and set along with the stars. However, positioned in the northern sky as it is, the Perseids radiant never sets at this time of year. The meteor shower continues day and night, and we just have to wait until it is sufficiently dark for a chance to spot the meteors streaking by overhead.

During the peak of this year's shower, the First Quarter Moon will be in the western sky for the first half of the night. While that will add to the sky's brightness until it sets around midnight, observers only need to turn their back to the Moon for their best chance to spot Perseid meteors and fireballs. Getting as far away from urban light pollution as possible will maximize that potential.

DON'T MISS: Euclid telescope shares astounding new views of the cosmos

The Seasonal Blue Moon

In the latter half of August, we will see something that hasn't graced our skies since 2021 — a seasonal Blue Moon.

Blue Moons are an astronomical rarity. They typically occur once every 3 years. However, if you've noticed them being somewhat more common recently ("didn't we just have one of those last year?"), it's not your imagination. The discrepancy comes from the fact that we currently observe two different types of Blue Moon.

The first type is "the third Full Moon in a season with four Full Moons." Basically, with one Full Moon typically occurring each month, you should see three each season, for a total of 12 Full Moons in a period of four consecutive seasons. However, once in a while, due to the timing of the Full Moons, you get a total of 13 Full Moons in the span of four seasons — three seasons with three Full Moons, and one season with four. This is what we are seeing in Summer 2024. The last 'seasonal Blue Moon' was in August 2021, and the next we'll see after this is on May 20, 2027.

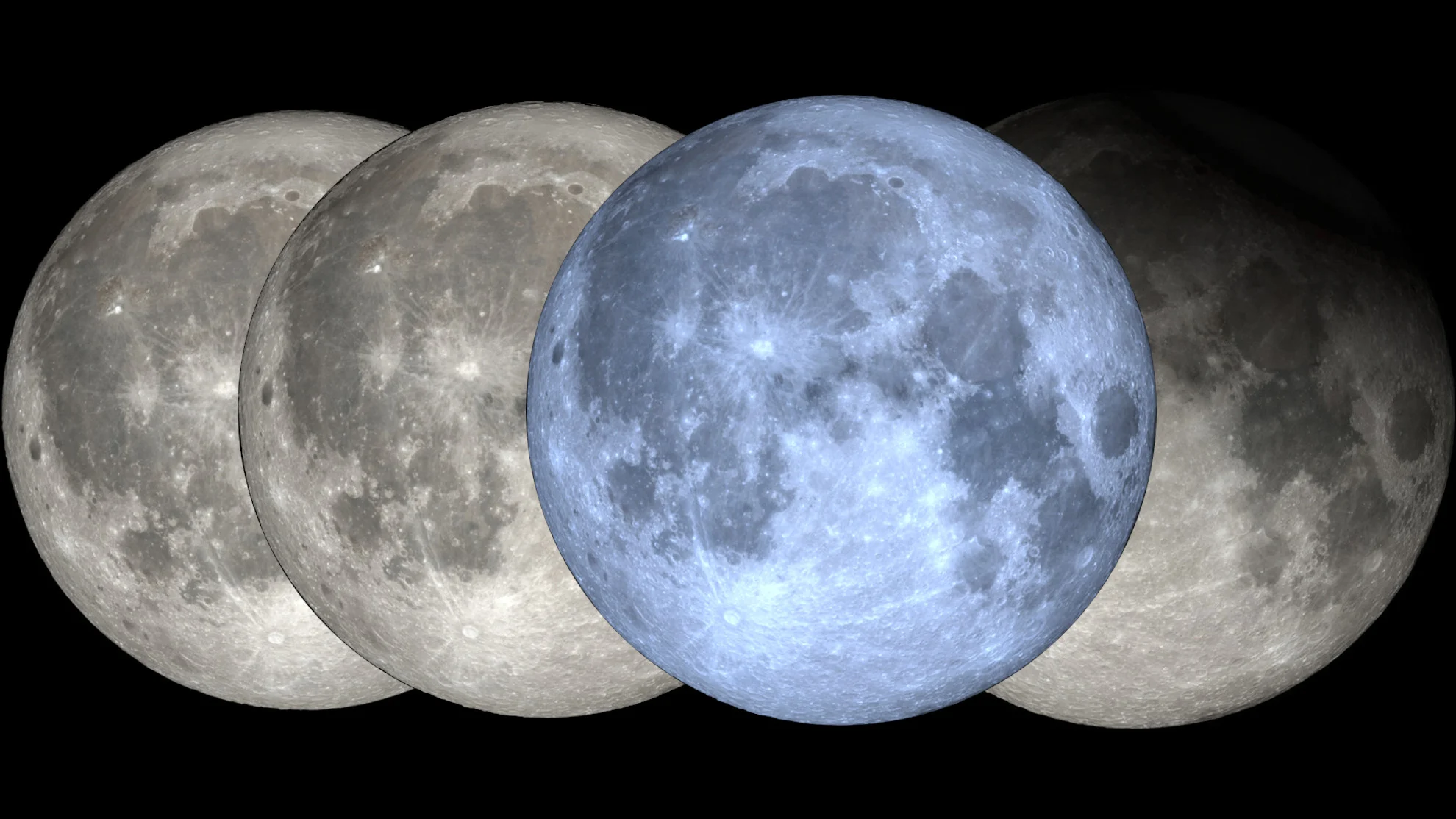

The four Full Moons of Summer 2024. Although the August Full Moon will likely not turn blue, it has been shaded that colour in this image to represent the event. The September Full Moon is darkened to denote the partial lunar eclipse that will occur on that night. (Scott Sutherland/NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

The other type of blue moon is "the second Full Moon occurring within a calendar month." In the same way that we typically have 12 Full Moons within four consecutive seasons, we also tend to see 12 Full Moons within a single calendar year.

Again, due to the fact that the timing of each Full Moon changes, though, one can fall on the first or second night of a calendar month. In that case, unless it's February, the next Full Moon will happen at the end of that same calendar month. That is the type of Blue Moon we saw in August of 2023, and we'll see the next on May 31, 2026.

The 12 Full Moons of 2024, including their popular names and any other notable facts — supermoon, micromoon, harvest moon, lunar eclipse. (Scott Sutherland/NASA GSFC, with data from Fred Espenak)

Now, will the Moon actually turn blue on these dates? No. Or, at least it's not likely.

The term "Blue Moon" simply denotes something that is rare. "Once in a Blue Moon," as the saying goes.

The Moon can turn blue, though. The Moon becomes a dusky red colour during a sunset or a total lunar eclipse because air molecules scatter sunlight — the shorter wavelengths (blue) are scattered first, followed by green and yellow. This leaves only orange and red wavelengths of light to either colour the sky (on any typical night) or be cast directly onto the lunar surface (during a total lunar eclipse).

However, if moonlight is passing through certain types of particles floating in the air, such as ash from a volcano or a forest fire, the opposite can occur. These particles can scatter the longer wavelengths of light first. Thus the reds and oranges are lost, and we see the Moon with a slightly more bluish tinge.

The Zodiacal Light

For about two weeks starting on September 1, turn your gaze to the eastern horizon in the half hour before the start of morning twilight. Specifically, you are looking for a diffuse white glow in the shape of a pyramid, with its base along the horizon and its peak extending high into the sky.

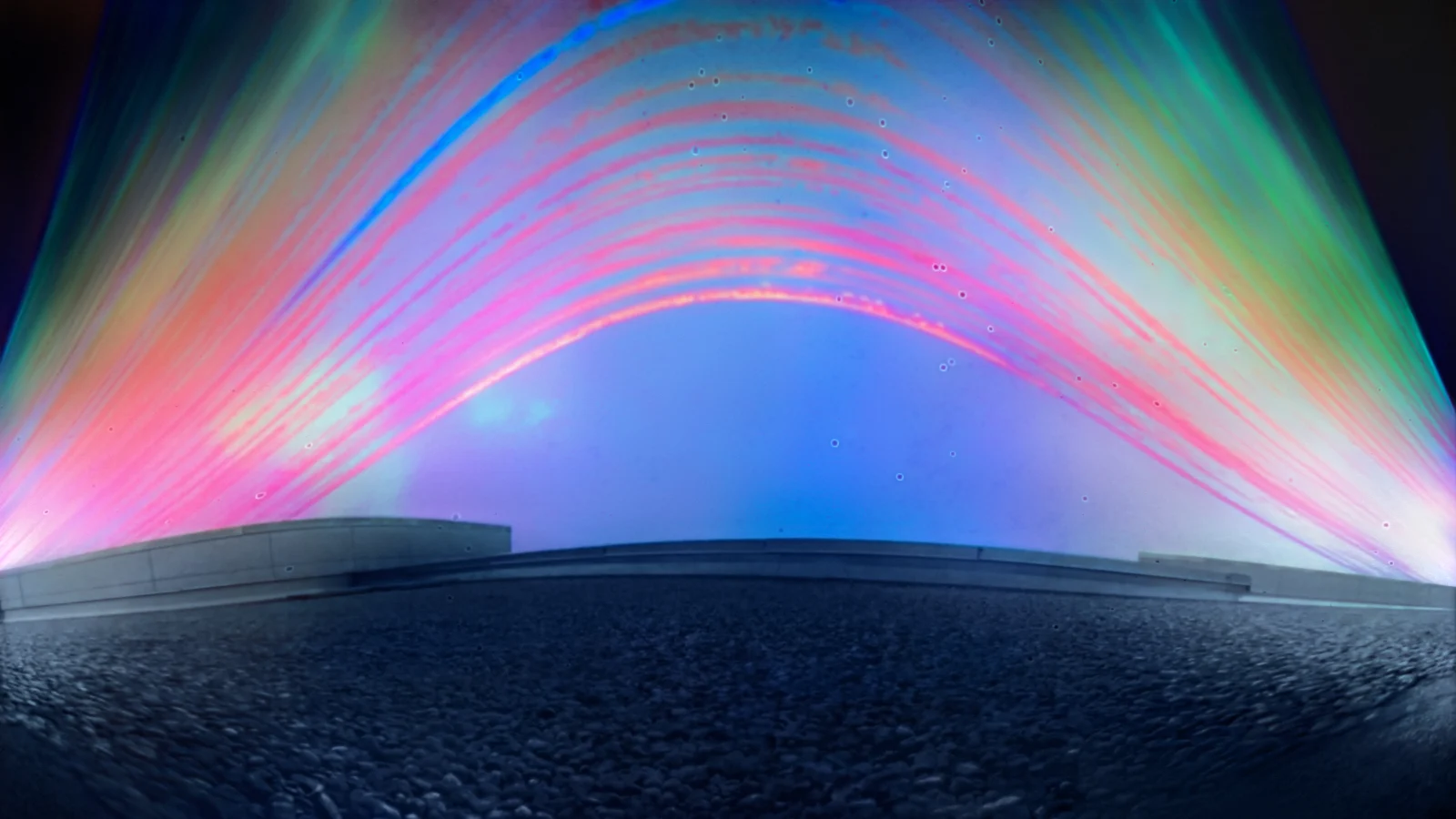

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: European Southern Observatory (ESO)

This is called the Zodiacal Light, which results from sunlight glinting off trillions of grains of dust that float in an immense disk surrounding the Sun.

Although this phenomenon has been observed for a long time, researchers recently shed fresh light it. Rather than originating from comets, data from NASA's Juno spacecraft revealed that it could be Martian dust lofted into space during planet-wide dust storms!

Viewing the Zodiacal Light is challenging; not because it is elusive in any way, but instead due to the fact that observers often mistake it for simply being part of twilight.

The best way to be certain you are actually seeing it is to look up the exact timing of twilight in your area. With that in mind, if you see this diffuse glow in the sky and it is still before twilight has begun, you can be confident that you've truly spotted this immense interplanetary dust cloud.

Super Harvest Moon Partial Lunar Eclipse

On the night of September 17, just days before the end of the season, a Supermoon will rise. Being the closest Full Moon to the fall equinox, this will also count at the Harvest Moon for 2024.

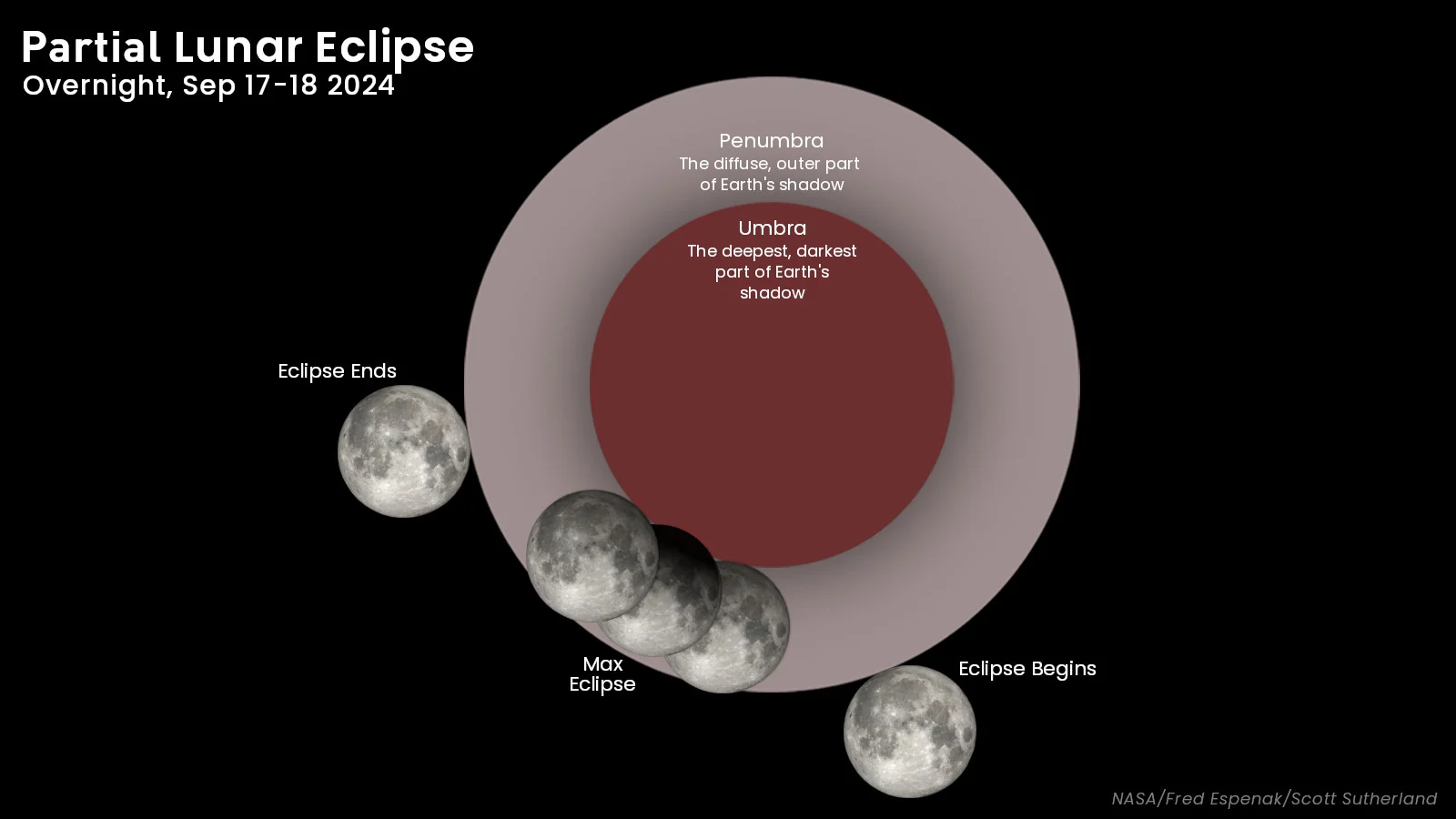

To top this off, starting around 8:41 p.m. EDT, the Moon will begin passing through Earth's shadow. It will be difficult to spot for the first hour or so after that, as Earth's penumbra only causes the Moon to dim slightly. Starting around 10 p.m. EDT, though, the shadow will deepen near the Moon's north pole, and from 10:12 to 11:15 p.m., that region of the lunar surface will darken significantly as it passes through the edge of the inner umbra.

The Moon's path through Earth's shadow during the September 17-18 partial lunar eclipse. (Scott Sutherland/NASA)

As only part of the Moon passes into the umbra, rather than its entire disk, this will be a partial lunar eclipse. The portion in the umbra will turn a reddish hue during the event. However, it will likely be difficult to notice this colour difference when contrasted against the rest of the Moon. Using a telescope or binoculars may help.

The entire event lasts just over four hours, with the Moon passing out of the penumbra at 12:47 a.m. EDT on Sept. 18.

Fall Equinox

At 8:43 a.m. EDT on September 22, the Sun will pass over the celestial equator headed south. This marks the fall equinox for the northern hemisphere.

Just as we saw with the spring equinox and the summer solstice, this is also the earliest fall equinox in a very long time.

The last September equinox that was close was 1896, when it occurred at 8:03 a.m. EST on the 22nd. However, to make a proper comparison, we need to subtract an hour ("fall back") from this year's timing — 8:43 a.m. EDT becomes 7:43 a.m. EST. So, that's even earlier than it was in 1896!

It turns out that we have to go back another full century, to September 22, 1796, to find one earlier than this year's fall equinox. On that day, 228 years ago, it occurred at 3:06 a.m. 'local mean time'. (LMT for Toronto was used here, which still compares well with EST for this comparison.)

Over the next three years, the equinoxes and solstices will get nearly six hours later, year by year. Then, in 2028, they'll shift back by a full 24 hours, and become even earlier than we are seeing now.