A world first, every tropical ocean saw a Category 5 storm in 2023

For the first time on record, every tropical ocean basin around the world has produced a tropical system with the equivalent strength of a Category 5 storm

For the first time since weather satellites began peering at our skies from above, each of the world’s warm oceans have seen a scale-topping tropical cyclone so far in 2023.

While we’d typically see at least one tropical system somewhere on Earth achieve this infamous milestone each year, we’ve never seen each of the world’s tropical ocean basins pump out a scale-topping storm all within the same year.

Many of the planet’s apex storms so far this year have been noteworthy for their ferocity, longevity, and the sheer speed at which they intensified.

MUST SEE: How a mammoth hurricane rapidly intensifies in mere hours

Different oceans, different names, but all the same storms

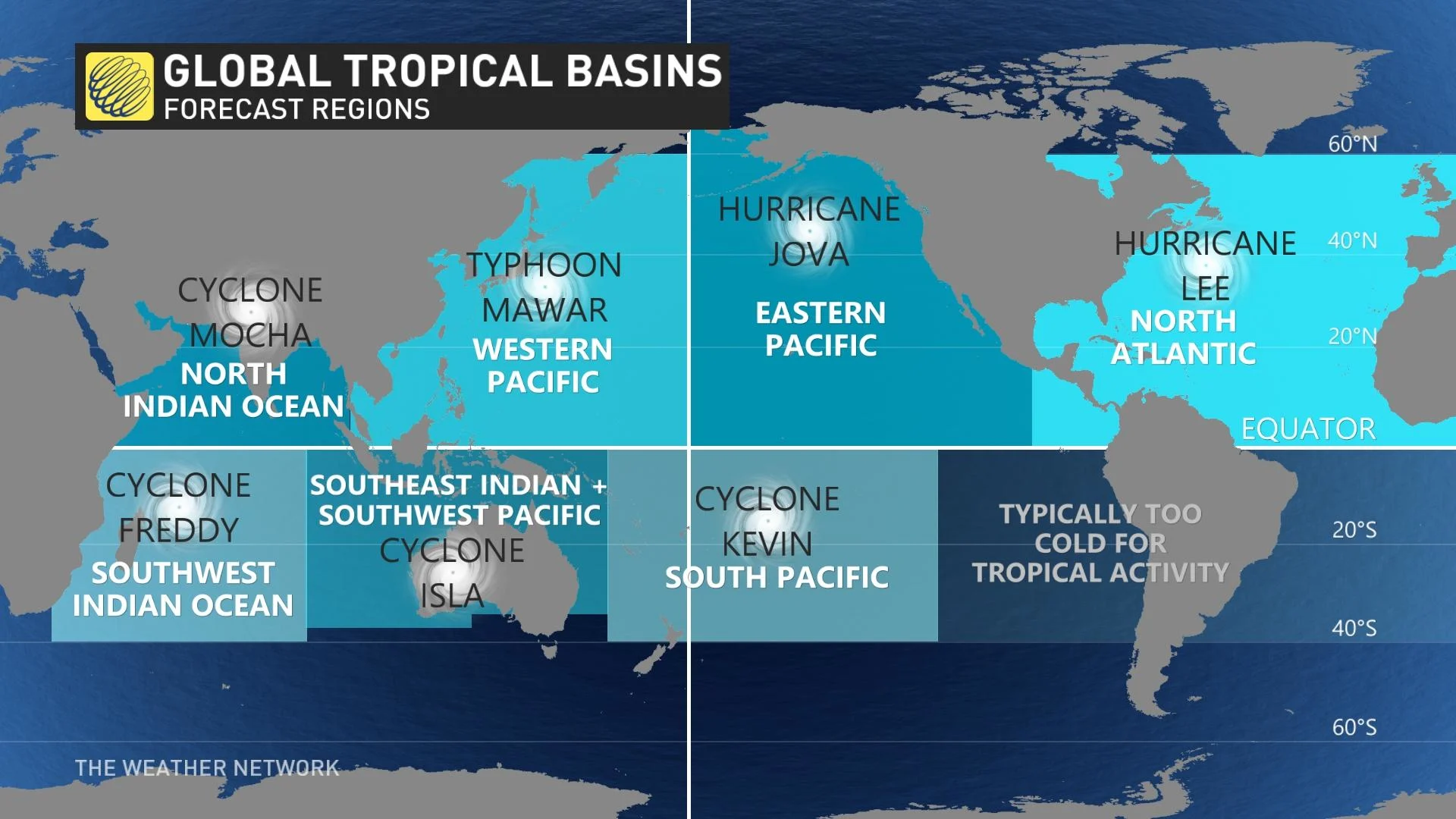

The Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans are broken down into ‘basins’ to make it easier to keep track of tropical systems throughout the year. There are seven major tropical basins split between the three oceans.

All low-pressure systems with tropical characteristics are called ‘tropical cyclones’, but each stage of a storm’s formation earns a different name around the world based on its maximum sustained winds.

Tropical cyclones that grow quite strong are called hurricanes in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, typhoons in the west Pacific near Asia, and they’re simply just cyclones everywhere else.

They’re all the same storm even if they have different names, and each basin so far in 2023 has produced a powerful hurricane, typhoon, or cyclone with the equivalent strength of a scale-topping Category 5 hurricane.

Cyclone Freddy was the longest-lived storm on record

The first Category 5 tropical cyclone of 2023 was a deadly powerhouse of a storm in the Indian Ocean that’s likely to secure a spot in record books as the longest-lived tropical cyclone ever observed.

Cyclone Freddy formed off the northwestern coast of Australia on February 6, continuing west across the entire Indian Ocean for more than a month.

The storm grew into a formidable force as it traversed the sunbaked waters, peaking in strength near the central Indian Ocean several times, once with sustained winds as high as 270 km/h.

RELATED: What the science says about hurricanes and climate change

Freddy rapidly weakened before making landfall on the mountainous island-nation of Madagascar, but it regrouped after crossing the island and made landfall on the African mainland in nearby Mozambique.

A calm environment allowed Cyclone Freddy to stall out across the region, forcing the storm to loop back toward Madagascar before once again returning to Mozambique, where it finally fizzled out on March 14.

The cyclone's drenching rains brought catastrophic flooding to the region, killing more than 1,000 people in Malawi alone, Reuters reported a month after the storm ended.

Meteorologists tracked Cyclone Freddy for five weeks and two days, making it the longest-lived tropical cyclone on record. The storm beat out the previous record-holder, set by Hurricane John’s 31-day run across the eastern Pacific in 1994.

WATCH: Hurricanes are growing more intense, and climate change is probably to blame

Hurricanes Jova and Lee exploded just hours apart

Two hurricanes rapidly intensified on either side of North America over the course of two days in September.

Jova formed far off the western coast of Mexico where it encountered very warm waters over the eastern Pacific Ocean. The system intensified from a tropical storm with 110 km/h winds on September 5, 2023, into a Category 5 hurricane with 260 km/h just 24 hours later.

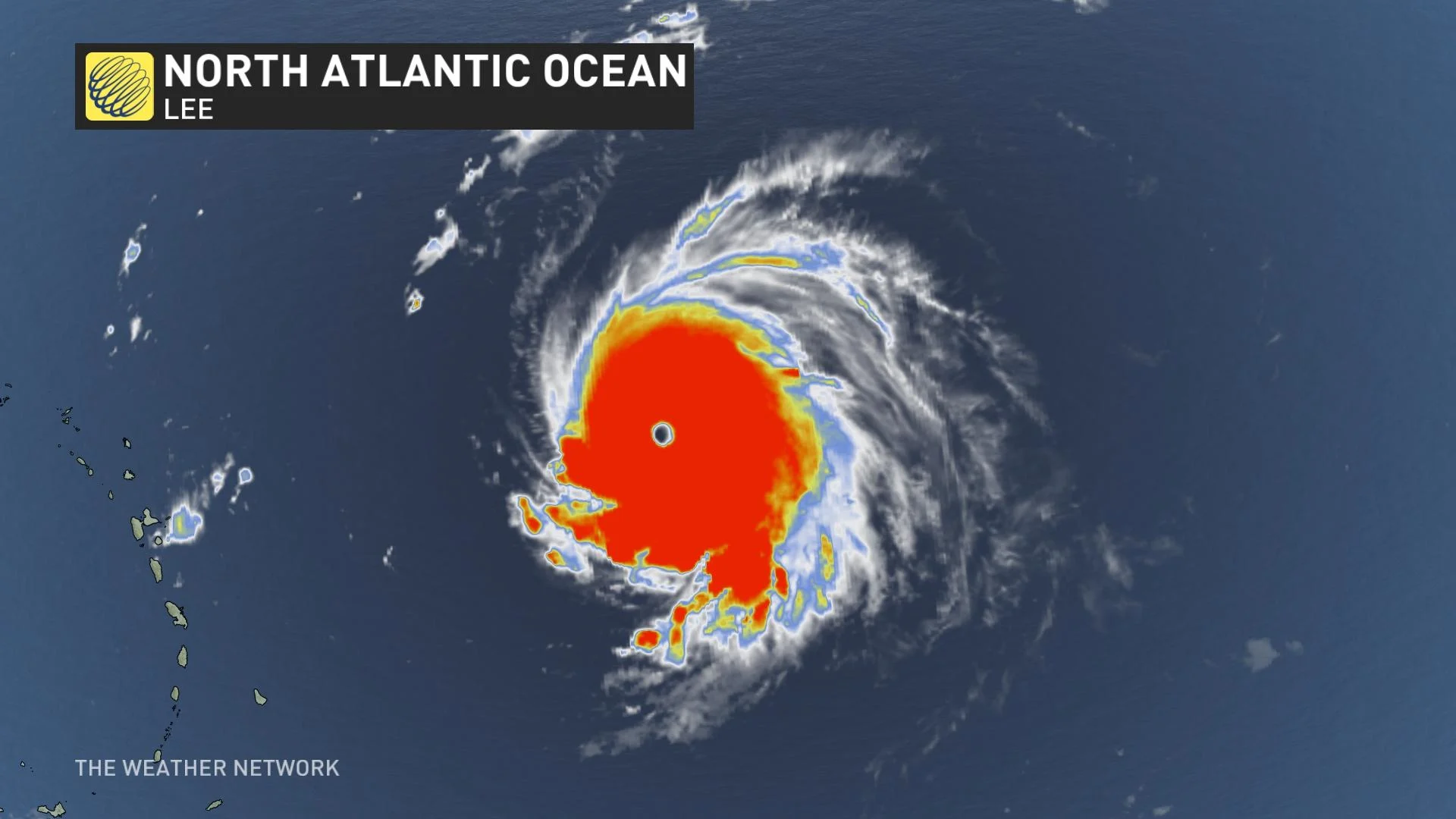

The following day, Hurricane Lee over in the Atlantic Ocean accomplished a similar feat. Lee rapidly grew its maximum sustained winds from 130 km/h to 270 km/h over a 24-hour period, one of the fastest bouts of intensification ever observed over the Atlantic.

Jova was the first scale-topping hurricane to form in the eastern Pacific Ocean since 2018, while Lee continued the Atlantic basin’s streak of producing intense hurricanes in recent years. Hurricane Lee was the eighth Category 5 storm to form in the Atlantic since 2016.

Mawar grew into the year’s strongest tropical cyclone

But the year’s strongest tropical system developed in the western Pacific Ocean back in May. Super Typhoon Mawar swiftly grew into a monstrous Category 5 equivalent storm when it peaked with maximum winds measuring as high as 295 km/h.

DON’T MISS: How hot water fuels the world’s most powerful hurricanes

Mawar, also known as Betty in The Philippines, where the country’s weather bureau uses its own naming system, narrowly missed the U.S. territories of Guam and Northern Mariana Islands, where structural damage and power outages occurred.

Thankfully, Mawar avoided making any direct landfalls, only bringing heavy rain and rough surf to The Philippines and Japan as it swept through the region.

Three more storms round out 2023’s historic feat

The hot waters around Oceania gave rise to another Category 5 cyclone at the end of February. Cyclone Kevin’s intense winds briefly reached the top of the scale after traversing the islands of Vanuatu. Kevin formed around the same time as Cyclone Judy, another powerful storm that followed almost the same track as Kevin just a few days earlier.

STAY SAFE: What you need in your hurricane preparedness kit

Waters off the northwestern coast of Australia gave birth to another scale-topping storm two months after Freddy began its historic journey.

Cyclone Ilsa rapidly intensified off the northwest Australian coast in the middle of April as it swirled toward landfall near Port Hedland, which sits about 1,400 km north of Perth. Ilsa hit the coast with the equivalent strength of a major hurricane, but the sparse population led to minimal damage.

Cyclone Mocha rapidly intensified in the northern Indian Ocean during the middle of May. Mocha’s maximum winds of 277 km/h made the storm one of the strongest on record in this part of the world. The cyclone weakened as it swept into land, unleashing deadly floods in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

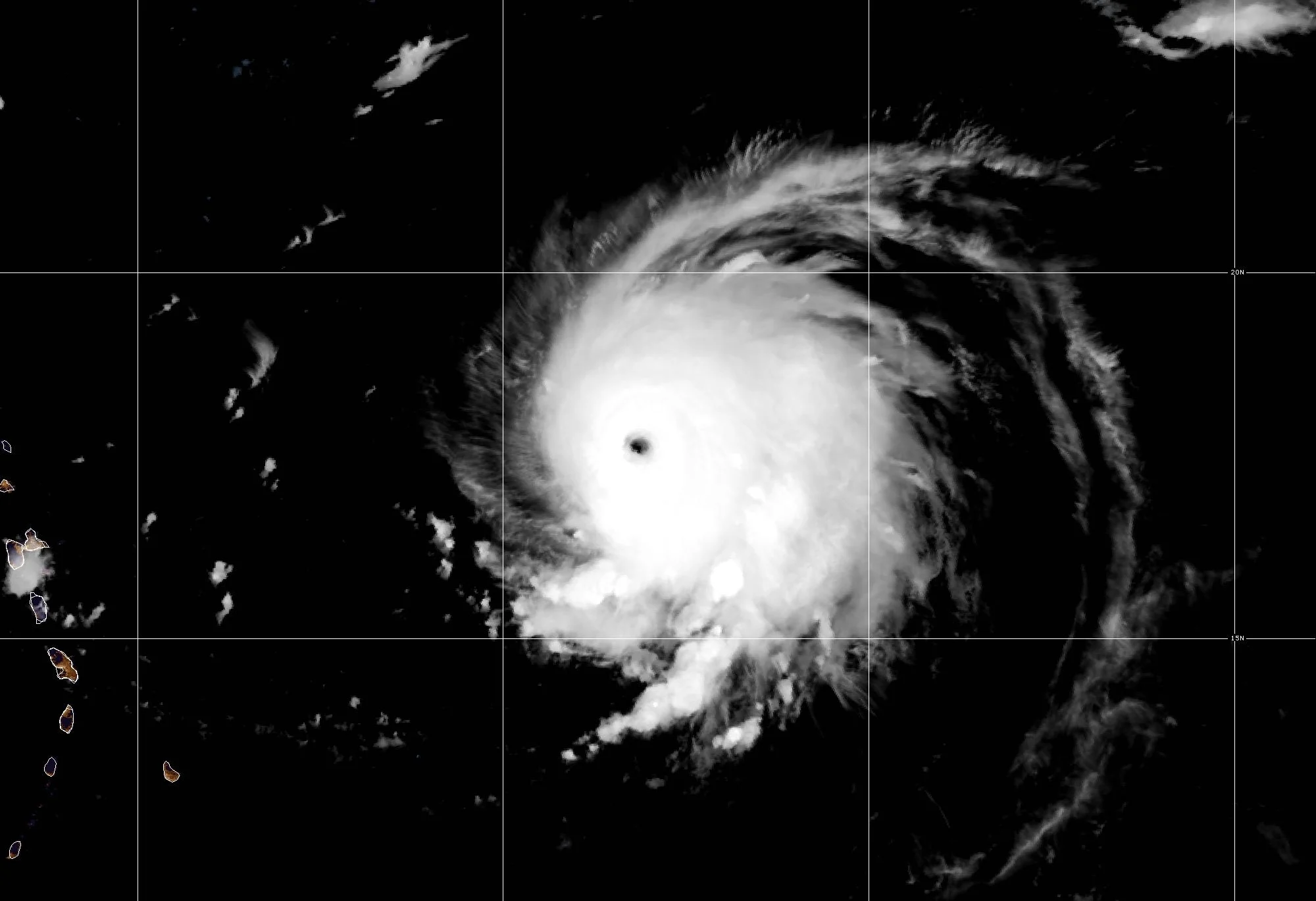

Header satellite image courtesy of NOAA.