Bold failures: 7 Canadian expeditions that ended in disaster

Attempts by Europeans to map out Canada's territory haven't always gone smoothly.

Canada's Indigenous people had long adapted to life in the country's vast territory prior to European contact. The first Europeans to arrive in the area, not so much.

Of the seven failed expeditions below, some were led by people who were extremely prepared and competent. Others, by inept megalomaniacs. All met disaster in some way, with some never returning alive.

JOHN CABOT

Giovanni Caboto, known to English speakers as John Cabot, took the long way round from being born somewhere in Italy to vanishing somewhere in the general vicinity of Newfoundland.

The far-travelled trader’s scheme for a more northern route to Asia than the one people thought Columbus had found took him first to the court of Spain, then to Portugal. Both apparently had their quota of explorers for the decade, but he managed to find a sympathetic ear from the English King Henry VII.

Even then it took him a couple of tries to reach any land. His first voyage in 1496 had to turn around, but the 1497 jaunt is believed to have taken him to Newfoundland and possibly even Labrador. If you’re wondering about “possibly”, we wrote that because the sources of his record are remarkably spotty.

Obviously he didn’t find any glistening Chinese cities, but he did famously encounter waters absolutely teeming with the cod that would form the backbone of Newfoundland’s economy for centuries after.

It was enough to intrigue the king, who rewarded the adventurer handsomely, and in 1498, Cabot set out again, this time with five ships and hundreds of men.

One was damaged in a storm, and had to turn back. The rest were never seen again, and Cabot was presumed lost to history.

Or was he? Newfoundland Heritage says there’s evidence Cabot’s last resting place was at Grates Cove on the Avalon Peninsula, where he either starved or was killed by the indigenous Beothuk peoples. But there’s still more evidence he may actually have made it back to England in 1500, dying months later.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

The confusion is weirdly fitting: No one is sure where he was born, and no one is sure where he died, or even IF he died.

Anyway, whether he’d made it back or not, the government would have considered him a failure anyway. Around then, they still thought they were looking for a route to the fabulous wealth of Asia, so a few barrels of cod and some forested islands would have been a bit of a letdown.

THE BROTHERS CORTE-REAL

North America is one of those rare places on Earth which the Portuguese DIDN’T reach before other Europeans, though not by much. But the vast North American continent, still largely unknown to Europeans at the dawn of the 16th Century, would claim the same toll of the Portuguese as it claimed of Cabot.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Explorer Gaspar Corte-Real took a stab at finding the northern route to Asia, sighting (but not landing on) Greenland in 1500. He made a second attempt in 1501 with three ships, and is believed to have reached Newfoundland and possibly Labrador as well.

The expedition did some surveying of the area (along with straight-up kidnapping several dozen Indigenous people), but though two of the ships made it back to Portugal, the one carrying Gaspar himself never did, and he was never seen again.

His brother, Miguel, managed to get funding from Portugal's King Manuel to go searching for the wayward explorer the next year. Just as with Gaspar, two of the three ships Miguel took with him made it home, while the third, carrying Miguel, did not. Nobody ever saw him again either.

The Corte-Real family hadn’t run out of brothers: Vasco Añes Corte-Real wanted to go find his siblings, but the king had run out of patience, and forbade the expedition for fear Vasco would vanish too, so the missing duo’s fate is lost to history.

HUMPHREY GILBERT

Humphrey Gilbert is most known to history as an explorer, which is a bit rich, given how terrible he was at it.

His first attempt at founding a colony in North America in 1578, numbering an impressive 10 ships and 570 men, completely fell apart without even reaching Newfoundland. Strapped for experienced sailors, Gilbert recruited pirates for much of his crew, who then pinched four of the ships for a spot of good ol’ fashioned piracy. Two other ships proved unseaworthy and needed to turn back, and supply problems finally sent the rest homeward bound as well.

Gilbert was persistent (as well as “vain, tempestuous and cruel,” according to the Canadian Encyclopedia), so in 1583, he gave it another shot, this time with five ships. Once again, the whole thing was a shambles from day one. One crew deserted only two days into the hard crossing to Newfoundland, and the pirate crew of another robbed a French ship on the way (They just couldn’t help themselves, we guess).

In Newfoundland at last, Gilbert turned into a bit of a megalomaniac, pronouncing grand plans for a colony without any realistic hope of achieving them (to the apparent bewilderment and amusement of the small flotilla of foreign fisherman that had been fishing off the island without incident for decades).

Somehow, it got even worse. His employed pirates started raiding the aforementioned fishermen, and he had to send the “malcontents” and sick back home in one of his four remaining ships before setting out again. Another ship ran aground and broke up, leaving the expedition without gathered specimens or maps.

Gilbert gave up and took his remaining two ships home, but the fates weren’t through with him. Caught in a storm, his ship sank with him aboard, and an eyewitness aboard its sister ship watched him go down, belting out passages from an open book from his doomed ship’s stern.

HENRY HUDSON

Like everybody else on this list, English explorer Henry Hudson’s life story has a lot of gaps in it. What we do know is that he was better at this exploration business than the other folks on this list, and that his worst enemies were on his own ship.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Hudson had already developed a reputation for trying and failing to find the northEAST passage -- a route to Asia over the north coast of Russia. The third time he gave it a shot, in 1609, he appears to have given up by ... Going completely in the opposite direction. He sailed aaaaaaaaall the way over to North America, blazing a trail past Newfoundland to Nova Scotia and the present-day U.S. northeast coast, including New York, whose Hudson River is named after him.

The Canadian Encyclopedia says this astonishing detour was in direct defiance of orders from his Dutch backers, who told him to head straight back to Amsterdam if he failed to find the northeast passage a third time. It’s possible he did it to build a case for English backing (he’d sailed for England before), and it seems to have worked. When he sailed a fourth time, in 1610, it was in an English ship, with funding from wealthy English interests, including the Prince of Wales.

His exploration skills were on full display during that voyage, which took him all the way into the enormous bay that bears his name, as far south as James Bay. But rather than heading back to England, Hudson made his crew overwinter on the bay. Angered at what they saw as dithering, and spurred on by onboard machinations among some of the sailors aboard, the crew mutinied, setting Hudson and eight others adrift in a lifeboat.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

None of the maroonees were ever seen again. As for Hudson himself, well, he did have a river in New York and a ginormous bay named after him, which we guess is better than nothing.

JAMES KNIGHT

There’s always going to be an air of mystery in any tale of a missing explorer, but the fate of James Knight has more than the usual question marks.

Knight was almost 80 when he set out with two ships for the fabled but increasingly-cursed Northwest Passage in 1719, with grandiose plans to search for new iron and gold mines, and sites for a new whaling industry. Behind him was a decades-long career with the Hudson Bay Company, where he rose from lowly carpenter to board member, with plenty of time spent on the bay’s shores as governor of the company’s expanding holdings, as well as extensive sailing experience.

That’s a lot of time to learn that life in the Arctic is really, really hard, and according to an historian quoted in Up Here Magazine, Knight took that experience with him; His ships were well-kitted, with sturdy housing materials and a stove and coal for overwintering. So it’s a puzzle as to how someone so well prepared could have ended up stranded on Marble Island, his ships sunk, not far from today’s Rankin Inlet (Kangiqliniq).

It wasn’t until the 1760s that another explorer, Samuel Hearne, could confirm the fate of the lost expedition, but the circumstances of the men’s deaths were unclear, and that gap in the record endures through the ages.

Hearne interviewed local Inuit people, who told him the last of the men died in 1721. Up Here says no graves were found at the site, indicating most of the men may have struck out for the mainland. Canada’s Register of Historic Places says there are “some” graves on the island and, heartbreakingly, the Marble Island website repeats a common story that the last survivor died while literally digging the grave of the next-to-last survivor.

JOHN FRANKLIN

Sir John Franklin has enjoyed a surge in posthumous popularity since the rediscovery of his two lost ships, Erebus and Terror.

They were famously lost in his disastrous final voyage in search of (you guessed it) the Northwest Passage. But Franklin was no stranger to disaster, having survived an earlier expedition that went so far off the rails it descended into murder, possible cannibalism, and near starvation.

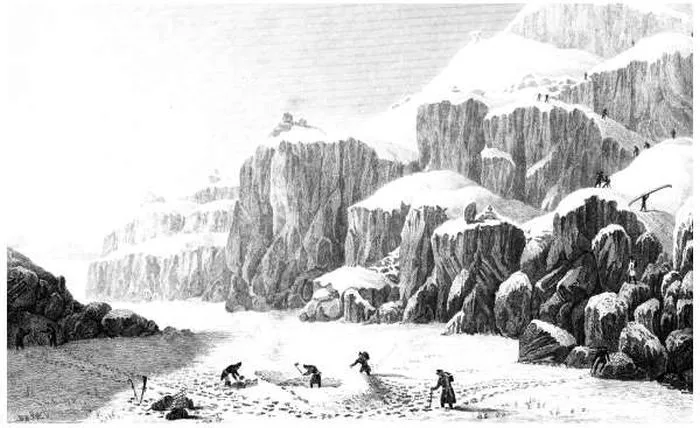

Depiction of John Franklin's party east of the Coppermine River. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

That would be the 1819 Coppermine Expedition, with Franklin and his men teaming up with French Canadian voyageurs and Indigenous people to map the northern mainland coast of the North American continent. Supply and organization problems left the expedition isolated far from aid and at the mercy of the hostile Arctic landscape. At one point, they were forced to subsist on lichen and their own boots (the Royal Society’s account says they were ‘lightly boiled’).

During this far-reaching nightmare, there’s one especially harrowing story: One group, travelling separately, was forced to make camp when two of their number, Hood and Richardson, became too weak to continue. They were saved when a third party member, Michel, came back regularly from the woods with what he called “wolf meat.”

Hood and Richardson grew suspicious -- three other party members had disappeared by that point, and they couldn't help but draw certain conclusions about where the meat was coming from. Those suspicions were only compounded when Hood was found shot dead (Michel claimed he accidentally shot himself cleaning his own gun, which was impossible given the length of the gun and the location of the wound).

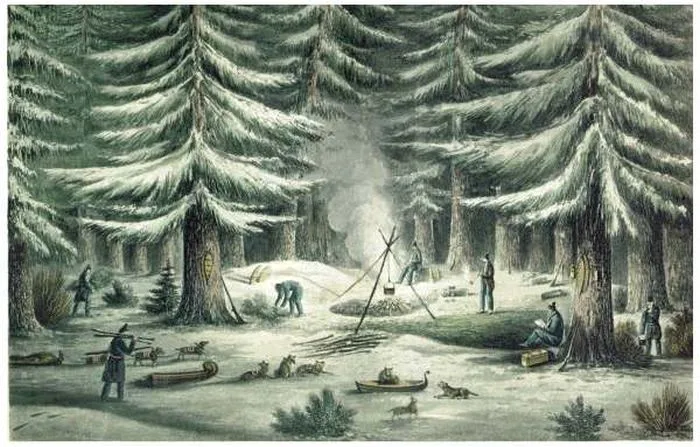

Franklin's party preparing to make camp. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

It was all too much for Richardson. At an opportune moment, he shot and killed Michel.

Eventually, the survivors linked up with Franklin’s party at a pre-prepared outpost, but starvation continued and the group would have died if not for some of Franklin’s Indigenous allies arriving with food and caring for the luckless explorers.

Franklin’s expedition was a failure, but he returned to the U.K. to a hero’s welcome for his survival in the face of adversity. He learned his lesson: A second attempt a few years later was much more successful, and made him a solid choice for his later 1845 attempt -- an infamous catastrophe that resulted in the loss of both his ships, as well as Franklin’s entire crew, again plagued with allegations of cannibalism. Read more about Franklin’s final voyage here.

THE VOYAGE OF THE KARLUK

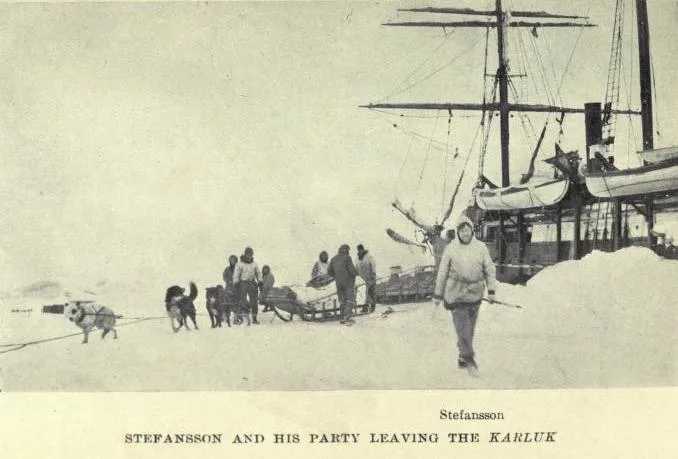

While others on this list hailed largely from elsewhere, the disaster of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913 was almost entirely made-in-Canada, meant to advance Canadian national goals and backed by Prime Minister Robert B. Borden.

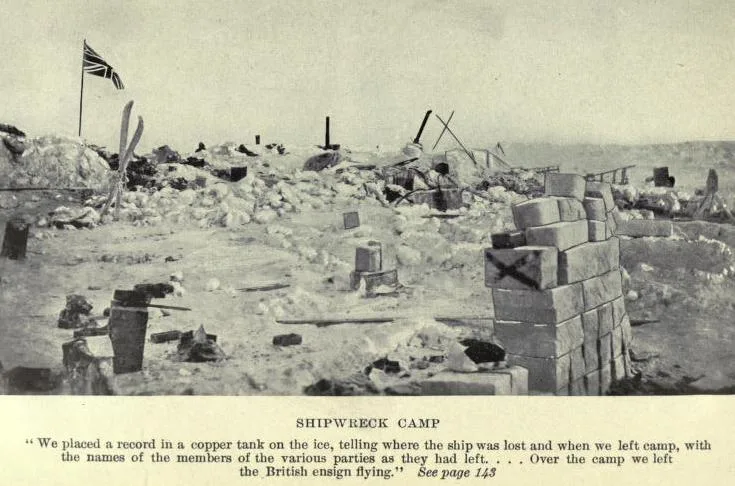

The expedition was intended to consolidate Canadian sovereignty over the North American Arctic, with its flagship, the wooden-hulled Karluk, setting off for Alaska in June 1913, and joined there by two other ships bought by the expedition. The ships split up, and the Karluk’s problems began, becoming trapped in the ice by August and gradually drifting toward Siberia. In January, the hull buckled from the pressure of the ice and the ship sank, leaving all 25 passengers and crew alive on the ice, but stranded in the near-total darkness of the inhospitable High Arctic winter.

From Bartlett & Hale: The Last Voyage of the Karluk (Wikimedia Commons).

The survivors would owe much to the ship’s captain, Bob Bartlett, who prepared the crew as best he could by directing them to make igloos on the ice and moving as many supplies off the doomed Karluk as possible (Not without a sense of black humour, it seemed: Heritage Newfoundland says Bartlett stayed on the ship until the absolute last minute, and set Chopin's "Funeral March” playing on his record player as it went down).

The crew made it to dry land at Russia’s Wrangel Island, but the Canadian Encyclopedia says eight either died or were never heard from again as they struck out for other destinations. As for Bartlett, he and Inuit hunter Kataktovik set off by sled across the wilderness, enduring a journey of more than a thousand kilometres, relying on Inuit villages for help and supplies, before reaching Alaska and sending a rescue. Even so, three more of the of the stranded explorers had died on Wrangel Island, bringing the human cost of the expedition to 11.

From Bartlett & Hale: The Last Voyage of the Karluk (Wikimedia Commons)

On top of everything else, by the time the survivors returned, the First World War had just begun, and the Canadian popular imagination had other things on its mind than Arctic sovereignty.

One survivor actually joined the British Army upon his return and, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, concluded that: “Not all the horrors of the Western Front, not the rubble of Arras, nor the hell of Ypres, nor all the mud of Flanders leading to Passchendale, could blot out the memories of that year in the Arctic.”