Record nine metres of melt observed on Alberta’s Athabasca Glacier

Canada's record wildfire season is likely having an effect on the Athabasca and other glaciers

Researchers say the 12-month vertical melt-rate observed on the Athabasca Glacier earlier this month "blows out" the previous record high melt-rate.

"Over the last ten years this glacier's been melting downward at a rate of four to six metres a year," said John Pomeroy, who is the director for the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for Hydrology. "This year, we have just short of nine metres of melt in the last 12 months, which blows the old record out by a tremendous amount, by two-and-a-half metres."

SEE ALSO: Most of Western Canada's glaciers will melt in 80 years, UNBC study finds

Pomeroy and his research team, who work out of the University of Saskatchewan’s Coldwater Lab in Canmore, completed the field observations September 14. They use a device called an ultrasonic depth sounder, which is attached to a long metal pole inserted deep into the glacial ice, to monitor both the melt-rate of the ice as well as snow accumulation and melt over the winter months.

Researcher John Pomeroy stands next to the ultrasonic depth sounder used to measure how much glacial ice is melting away from the Athabasca Glacier. (Connor O’Donovan/The Weather Network).

According to Pomeroy, all that glacial water is running away from persistent above-average warmth.

"We had a very warm fall last year, it was still melting in September and October, and then it started melting this year in April and May," Pomeroy explained. "Banff had a record warm May, and then warm temperatures through June, July and August."

Pomeroy says that Canada's record wildfire season is likely also having an effect on the Athabasca and other glaciers. He says wildfire smoke can darken the glacial surface with soot, reducing its reflectiveness.

"That darkening causes something called the albedo effect where the reflectance of the glacier drops," explained Pomeroy, whose team is still working to determine how the albedo effect impacted the Athabasca Glacier this summer.

"The less reflectance of solar radiation there is, the more energy that is absorbed by the ice and the faster it melts."

Researchers observe the accumulation of algae, soot and other organic matter on the Athabasca Glacier. (Connor O’Donovan/The Weather Network)

He adds algae can colonize the liquid water, soot and other deposits on the glacier and can form a dark substance called cryoconite, which also darkens the glacial surface and accelerates melting.

RELATED: Climate impacts are worsening faster than they ever have on record

The Athabasca research site is one of 35 glacial research sites across the Alberta Rockies that Pomeroy's team observes.

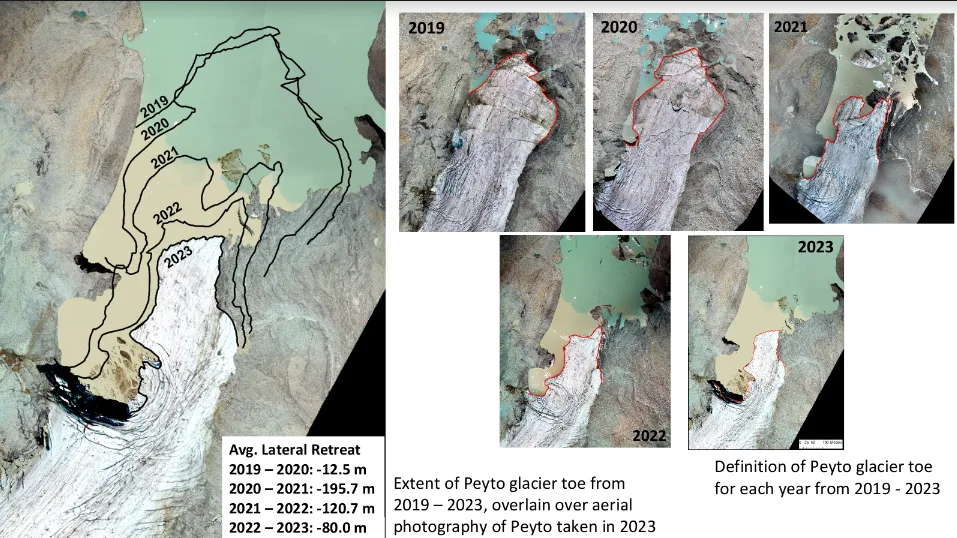

Aerial photography shows the retreat of Peyto Glacier, which feeds the North Saskatchewan river. (John Pomeroy, provided)

He says the melt observed at the Athabasca Glacier, which has more than half of its volume since the start of the 1900s, is symbolic of what’s occurring at other sites too. For example, new data shows vertical melt at Peyto Glacier, which Pomeroy’s team studies in even greater detail than Athabasca, was around four to eight metres this past year - also a new record.

Researchers use connectible ice augers to drill down into the glacier so they can set observational equipment deep enough to record multiple metres of ice melt. (Connor O’Donovan/The Weather Network).

"Nine metres (at the Athabasca Glacier) is one third more ice melt than has ever been recorded here. That shows us we’re in a bit of an emergency after this exceptionally warm and low-snowpack year," Pomeroy said, pointing out that communities across Canada and the northern United States depend on these glaciers for water use in cities, hydroelectric facilities and irrigation networks.

"The Pyrenees in Spain are losing their last glaciers this year, so there are mountain ranges where they’re losing them all. But we still have them here in the Rockies. We need to appreciate them, and we need to save them. "

A new lake has formed at the snout of the Athabasca Glacier. Pomeroy says it’s only formed in the past few years. (Connor O’Donovan/The Weather Network)