Satellite images tell tale of where Fiona took biggest toll on P.E.I. forests

P.E.I. government officials now say about 13 per cent of the Island's forested area was affected by the extreme high winds that accompanied post-tropical storm Fiona in September 2022.

"Affected" by Fiona in this case represents forested land where at least 70 per cent of trees were blown down, MLAs on the province's environment committee were told Thursday.

SEE ALSO: Hurricane Fiona, one year later: Could it happen again?

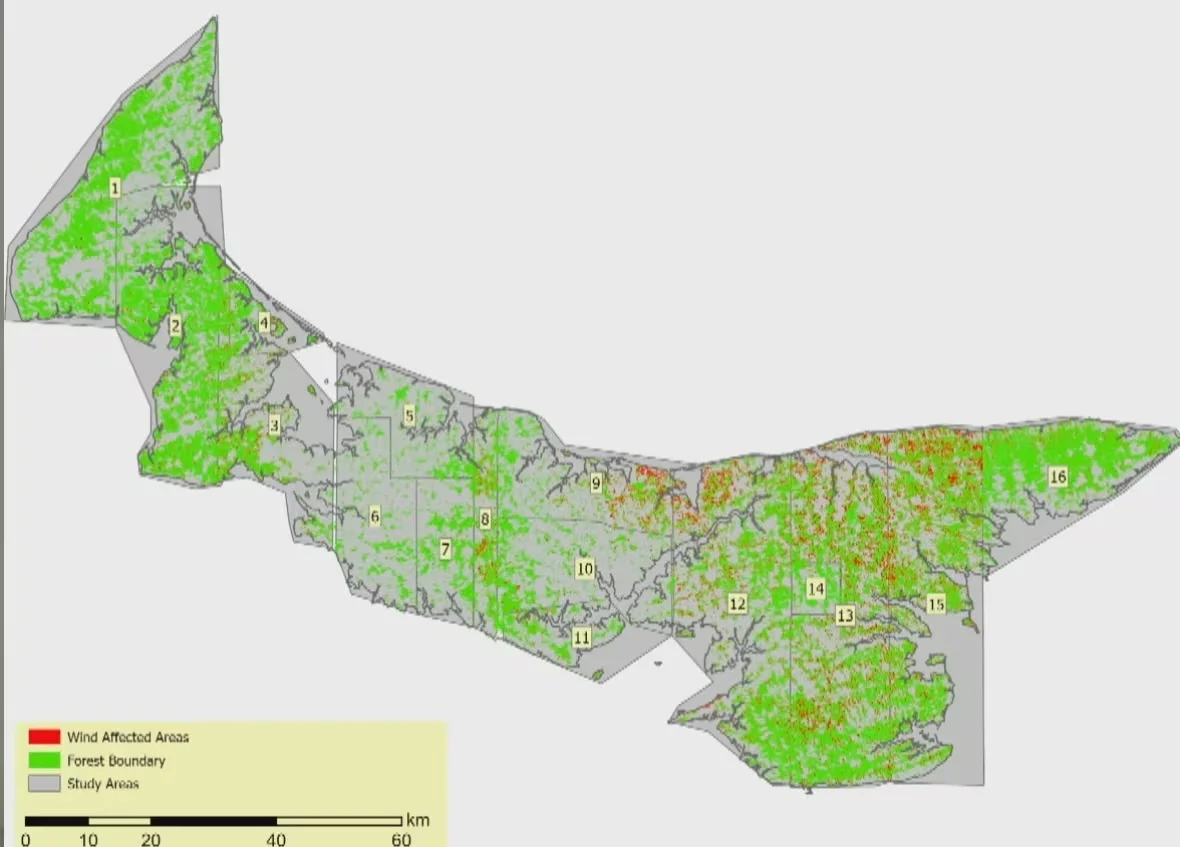

The eastern part of the province was left with 18 per cent of its forested land affected, compared to 12 per cent in central P.E.I. and only five per cent in the western part of the province.

"It doesn't mean that every stick of wood in that area is blown down, but those are the most heavily affected areas," said Kate MacQuarrie, the director of Forests, Fish and Wildlife for the Department of Environment, Energy and Climate Action.

The difference is most obvious when broken down into smaller regions, MacQuarrie told MLAs.

About 28.9 per cent of forested area on P.E.I.'s North Shore had at least seven in every 10 trees blow down, while the percentage in East Prince was only 1.6 per cent.

A map of the wooded areas on P.E.I., with small red patches showing where at least 70 per cent of trees in a forest were blown down by Fiona. The numbers show the boundaries of the satellite images used to analyze the wood loss. (Government of P.E.I.)

She noted that some wooded areas "may just not be possible to salvage given the time and cost associated with it. It's heartbreaking, but I take some solace in knowing that… our forests are resilient and in the lifetime of the forests they will recover."

The new data comes from analysis of 16 high-definition satellite images of the Island that the province commissioned after Fiona swept over the Maritimes.

Forestry officials have used the data to start planning how to compensate for the loss of trees, which represent not just wildlife habitat and carbon capturing for the province, but dollars and cents for P.E.I.'s estimated 16,000 woodlot owners.

MacQuarrie said salvage efforts on publicly owned land has begun with areas with a high degree of softwood blowdown, with an eye to reducing possible wildfire fodder as well as recovering some value for the wood.

So far, contractors have gone through about 244 hectares of public land, at a net cost to the province of $340,000 once salvaged wood has been sold.

A salvage operation is conducted at a P.E.I. woodlot last winter. (Shane Hennessey/CBC)

The department has no breakdown in terms of how much salvage has occurred on private land, other than 460 hectares for which the province has provided incentives for salvage.

The incentives average $1,140 per hectare. MacQuarrie noted that at that cost, it would take $39 million in funding to salvage all the private land that is classified as "affected by Fiona."

"The actual decisions are up to individual private woodlot owners in terms of what they want to do on their own lands," she told MLAs. "So some areas will be salvaged. Some areas' woodlot owners will choose not to for various reasons.

Replanting the land is another matter.

The province is increasing production of saplings at its J. Frank Gaudet Tree Nursery by 30 per cent as it anticipates a higher demand from reforestation projects in the years ahead.

A mechanized seeder is shown being used at the J. Frank Gaudet Tree Nursery in a 2018 file photo. At that point, the provincial nursery was making 700,000 seedlings a year available to Island woodlots. (Randy McAndrew/CBC)

MacQuarrie said careful attention is being paid to which types of trees should be grown for that purpose, noting that red oak and white ash are varieties that are expected to grow well given current projections for how climate change will affect the Island.

However, climate change will also boost the fortunes of pests, she said.

"A disease called oak wilt is marching north… [and] emerald ash borer is on our doorstep in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia."

As for the risk of wildfires taking hold in parts of the province where tree debris is drying out on forest floors, MacQuarrie said she is aware of it, but "it's not what's keeping me awake at night right now."

Tree planters head into a forested area in P.E.I. National Park this summer. Wooded areas on the province's North Shore suffered the most damage from Fiona's winds, according to satellite imagery. (Submitted by P.E.I. National Park)

She said lightning-caused fires are much rarer here than in Western and Northern Canada, and any fires that do start on P.E.I. tend to be stemmed by the "very highly fragmented landscape here — lots of fields, lots of roads, lots of natural fire breaks."

MacQuarrie also said the province has been training more forest firefighters and boosting its prevention measures.

"If people are smart, then that will keep the number of fires low," she said. "Our ability to respond is at an all-time high."

WATCH: Months after Fiona, this devastated town is still in shock

Thumbnail courtesy of Tony Davis/CBC.

The story was written by Carolyn Ryan and published for CBC News.