Great Fire of London could have been managed with better leadership

On this day in weather history, the Great Fire of London had already burned thousands of homes.

This Day In Weather History is a daily podcast by The Weather Network that features stories about people, communities, and events and how weather impacted them.

--

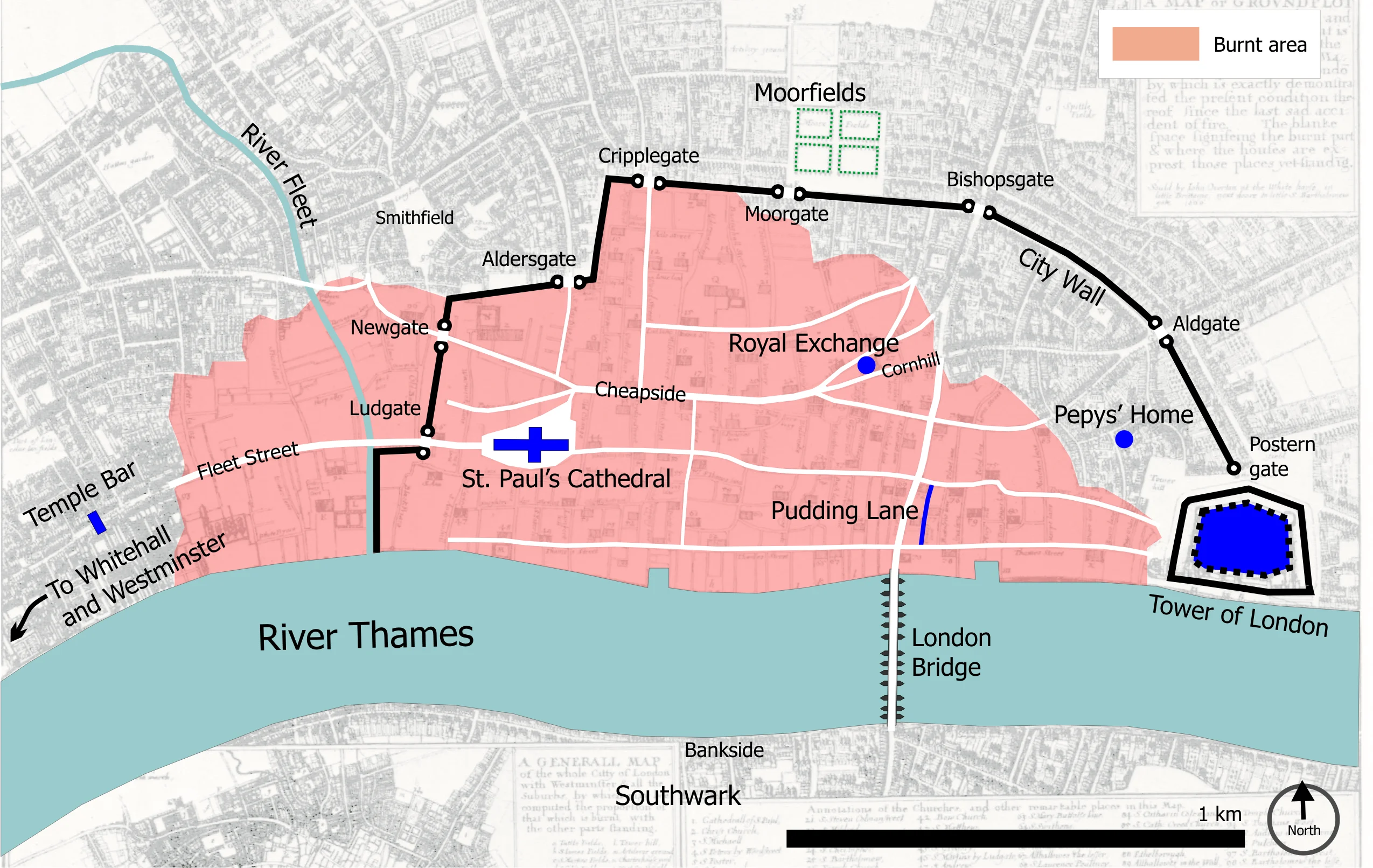

From Sept. 2-6, 1666, a major fire swept across central areas of London. The fire destroyed 13,200 homes, 87 parish churches, and most of the city's official buildings.

It all started at Thomas Farriner's bakery in Pudding Lane, shortly after midnight. The family on top of the bakery escaped but the maid did not make it out and died. Their neighbours tried to help extinguish the fire but to no avail. Local constables recommended that the adjoining houses should be demolished to manage the fire. The home dwellers protested, so Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bloodworth was called to override the objection.

"The Great Fire of London, depicted by an unknown painter (1675), as it would have appeared from a boat in the vicinity of Tower Wharf on the evening of Tuesday, Sept. 4, 1666." Courtesy of Wikipedia

Experienced firemen also suggested that the surrounding buildings should be demolished, but Bloodworth didn't heed. He said that the buildings' owners weren't around to give it the demolition an "OK." Bloodworth said, "A woman could piss it out."

Strong winds quickly spread the fire, and by Sunday morning, locals had abandoned their homes. The floods of people made it difficult for firemen to reach the fire.

By Sunday afternoon, the firestorm was raging and created its own weather. The chimney effect caused a rush of hot air to move upward on top of the fire, creating a vacuum on the ground. This added more fuel to the fire and caused the flames to rush towards the city's centre.

"Central London in 1666, with the burnt area shown in pink." Courtesy of Bunchofgrapes/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0

On Monday, the flames reached the financial district. As the fire threatened bankers' homes, they quickly tried to save their gold. John Evelyn, a courtier and diarist, wrote, "The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning..."

"...I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them," Evelyn added.

On Tuesday, the fire was most destructive. St. Paul's Cathedral was completely destroyed.

"Ludgate in flames, with St Paul's Cathedral in the distance (square tower without the spire) now catching flames. Oil painting by anonymous artist, ca. 1670." Courtesy of Wikipedia

By Tuesday evening, the wind died down. On Sunday, it rained, finally extinguishing the fire. But there were still burning coal around the city around two months later.

There aren't any official records about how many people died in the fire.

To learn more about the Great Fire of London, listen to today's episode of "This Day In Weather History."

Subscribe to 'This Day in Weather History': Apple Podcasts | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | Spotify | Google Podcasts | iHeartRadio | Overcast'