Ottawa's tornado caught forecasters off guard, but WHY?

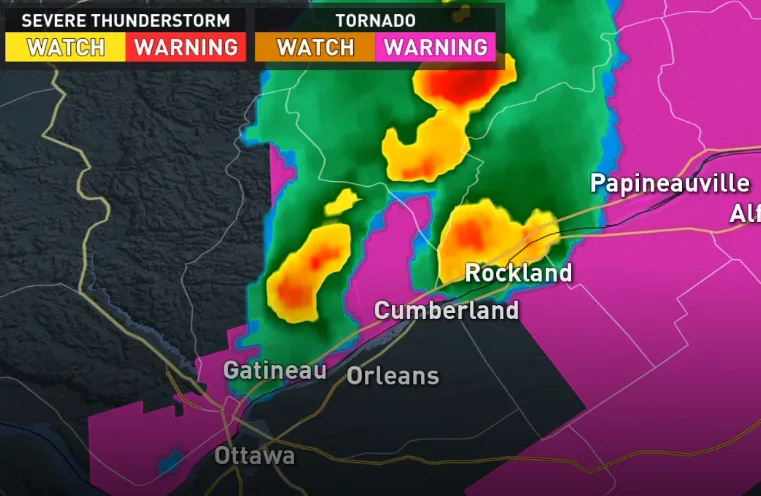

An otherwise tranquil day in eastern Ontario took a dramatic turn on Sunday evening when a bright white funnel cloud descended over the Ottawa River. The tornado, which has been given the initial rating of EF-1 formed about 10 km southeast of Gatineau just before 6 p.m. and went on to tear a damaging path through Orleans.

While forecasters had their eyes on the region for potential severe weather on Sunday, it's safe to say the tornado caught meteorologists off guard.

So what makes this tricky tornado special?

Summer revealed! Visit our Complete Guide to Summer 2019 for an in-depth look at the Summer Forecast, tips to plan for it and much more

Ultimately, that's a question that will likely attract a variety of researchers and grad students alike, but we can see some clues if we look at the atmosphere at the time of the storm.

WATCH BELOW: WARNING SYSTEM IN ACTION

WERE ALL THE INGREDIENTS PRESENT?

Thunderstorms, particularly those that go on to produce tornadoes, are finicky beasts. While it's true that any severe storm can produce a tornado, they need a lot of ingredients to be aligned just so to develop to their full potential. Among these are moisture in the atmosphere, a source of lift, inherent instability, winds that change with height and with direction, and a particular environment between the bottom of the cloud and the ground.

Some of these ingredients were forecast to come together on Sunday, and that had forecasters eyes on the region for the risk of storms that might produce damaging winds, small hail, and torrential downpours.

The main ingredient missing from Sunday's storm was one of the most important for tornadoes -- the changing winds, or what's known in the weather business as shear.

To support a very large thunderstorm, you need speed shear, a situation where winds are stronger the further up you go in a storm. For a tornado to form, forecasters look for directional shear, where the winds not only increase in speed but change in direction.

Based on forecast data, very little of either of these factors was expected for the Ottawa Valley on Sunday afternoon. The lowest levels of the atmosphere were also fairly dry, as evidenced by pictures of the twister swirling ahead of generally clear skies.

That's not to say there was none of these ingredients available; there was, but in quantities so marginal it didn't spark interest. To put it a different way, if forecasters raised the alarm for tornado risk for every situation with this kind of setup, there'd be a tornado risk every day of the summer.

RELATED: Northern Tornadoes Project 2019 aims to capture every Canadian twister

WATCH BELOW: ARCHIVED RADAR OF THE ORLEANS STORM

SOMETHING SPECIAL ABOUT THE OTTAWA VALLEY?

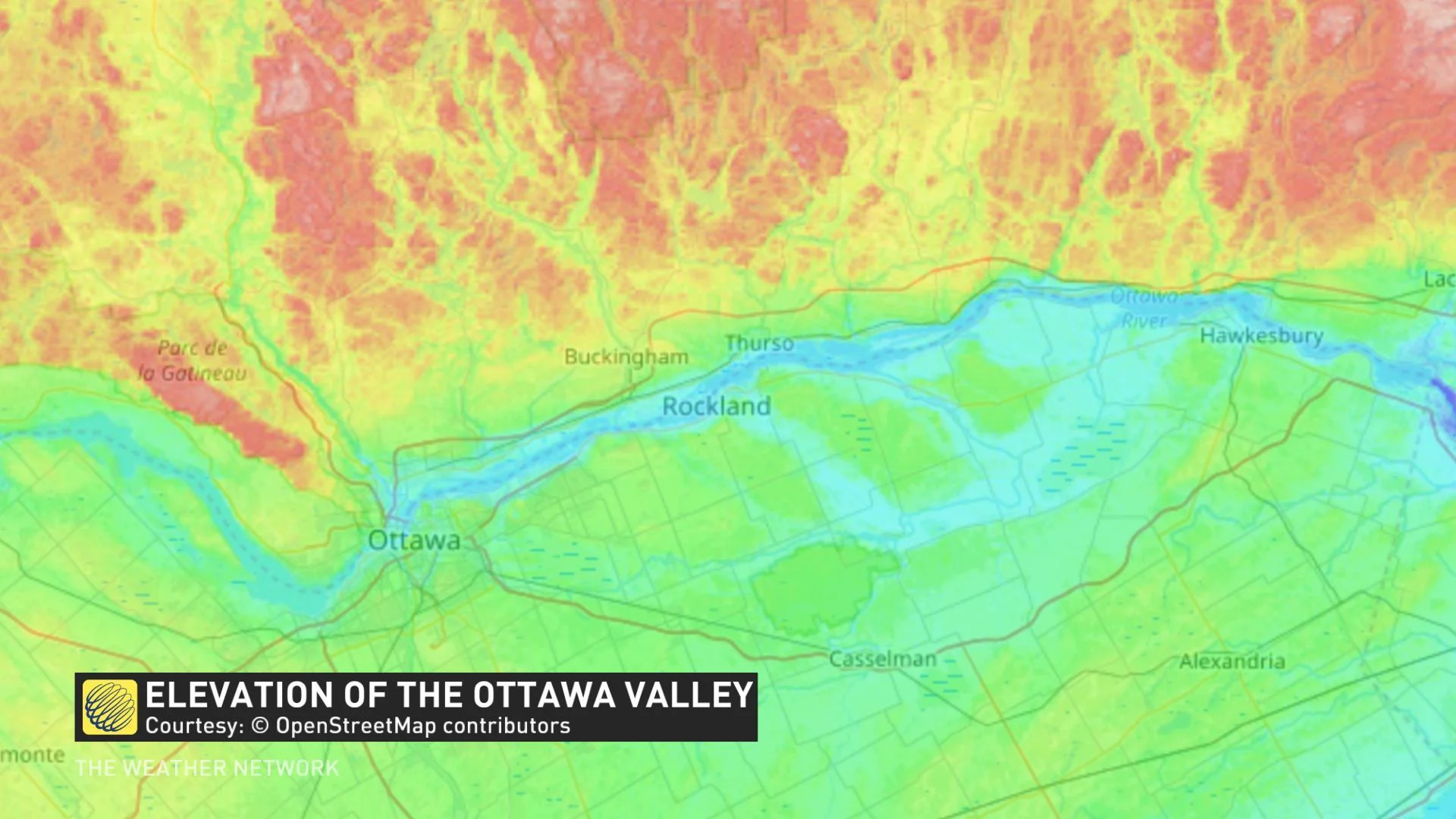

The Ottawa area is no stranger to tornadoes, but is it something specific about the region that makes these 'less than impressive' storms suddenly turn ferocious?

The potential is definitely there. The topography in the region presents some unique opportunities for storms, with local winds in along the river valley and the abrupt change in elevation north of the river playing a role in how storms develop and how they move.

In the case of Sunday's storms, it also looks like the interaction between storm cells -- or perhaps between the storm cells and the terrain -- played a role in the rapid intensification of the storm. Only about 25 minutes elapsed from the time the cell first appeared on radar to reports that the tornado was on the ground. That's about as fast as that development can happen.

At the end of the day, however, we just can't say for sure at this point. Though tornado research is a rapidly growing field in Canada via initiatives like the Northern Tornadoes Project, the reality is we're a big country with a lot of ground to cover (literally) and a relatively small population of researchers in atmospheric science.

If anything, cases like this go to show how much there still is to learn about severe weather, and that even when all eyes are looking in the right place, complex weather can still get the better of us.