What’s the recipe for a severe drought in Western Canada?

Coming off an incredibly dry 2023, Alberta is looking for some major help from nature over the remaining winter months and spring to hydrate the province. The Weather Network's Connor O'Donovan has the mid-winter drought outlook for Alberta.

After an exceptionally dry 2023, drought is on a lot of minds in Canada this winter.

In Alberta, the provincial government has drafted an emergency plan to deal with drought in 2024 and has put together a “drought command team” that will be working with water license holders to develop new ways to share and manage water in the year ahead. After more than 20 municipalities declared agricultural emergencies in 2023, Alberta’s farmers are certainly eyeing the skies with concern as well, and its fire chiefs have expressed concern about the impact of dry weather on wildfires in the season ahead.

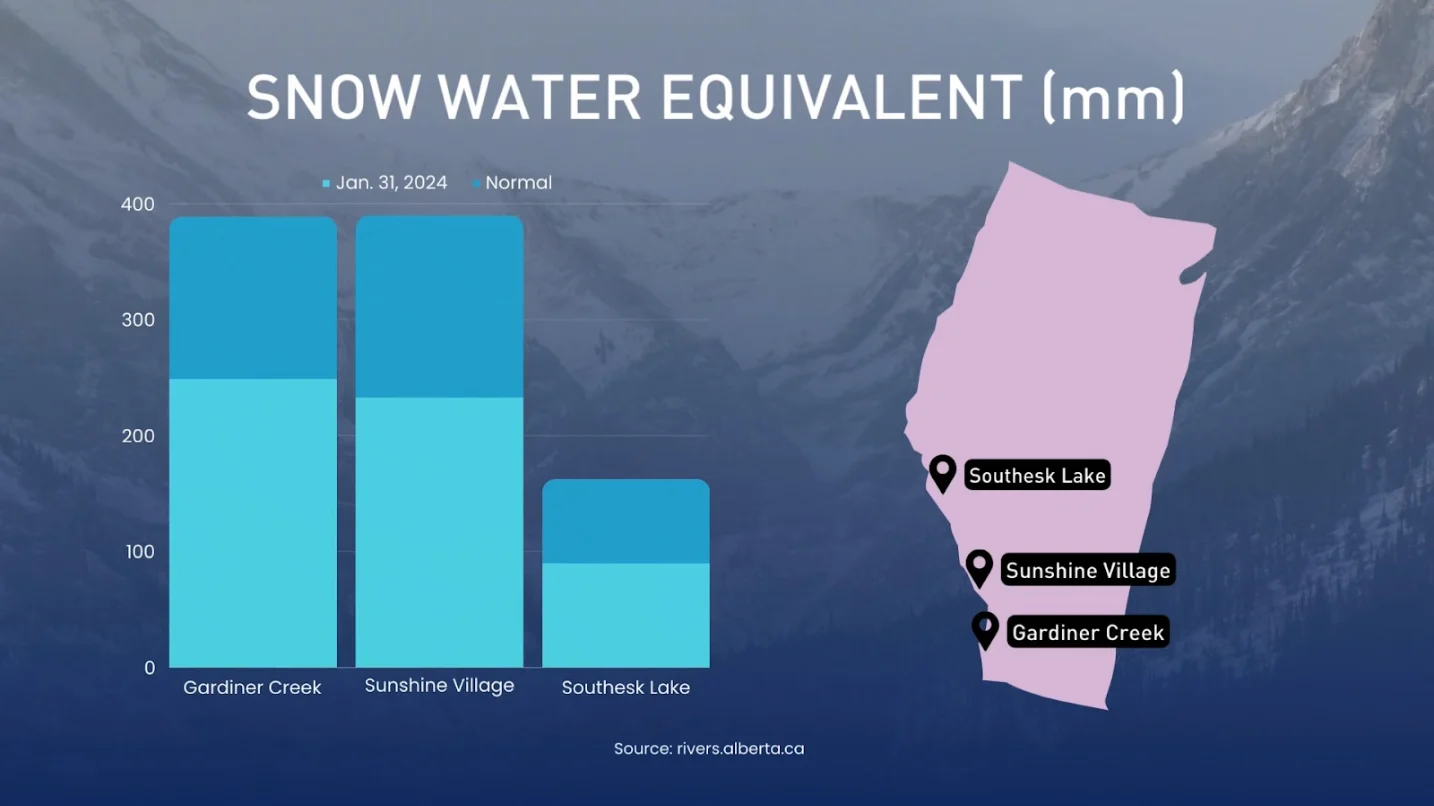

Snowpack levels are well below normal in many parts of Alberta, which hydrologists say is an indicator of a likely drought year to come. Source: The Government of Alberta)

RELATED: More Alberta communities impose water restrictions as drought continues

So what is the environmental recipe for a severely impactful drought, and what ingredients are already in the climate kitchen as we move through 2024? We can look to 2023 for a hint.

“Low mountain snowpack, early melt then extreme heat, high evaporation rates and lack of summer rainfall,” says hydrologist John Pomeroy of the conditions that contributed to drought last year. Pomeroy is the Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, and the director of the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for Hydrology.

“We’ve never seen a hydrological year quite like this in Western Canada.”

As Pomeroy says, 2023 saw “some of the lowest stream flows ever recorded” on water systems like the Bow River, record wildfire seasons in Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan thanks to dry conditions, water use restrictions in major cities, shrinking water reservoir levels, early irrigation shutdowns, and low agricultural yields in some parts of Alberta as communities across the province declared agricultural emergencies. In its December 2023 drought assessment, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada declared 70 per cent of the country “abnormally dry or in moderate to exceptional drought,” including 81 per cent of Canada’s agricultural landscape. Hydropower production was also affected in Manitoba and British Columbia.

Pomeroy’s University of Saskatchewan research team also recorded record-high ice melt in the Columbia and Wapta icefields, which could lead to longer-term water supply issues.

“It started with some record heat and rapid melt of the very low mountain snowpack in the spring,” Pomeroy says.

“Low snowpacks and low water storage in the Rockies will affect things right through Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, and of course British Columbia, and then down into the US Pacific Northwest, and north into the Northwest Territories.”

Parts of Western Canada then saw record heat in the spring and below-normal precipitation throughout the year.

Prairie water reservoir levels fell in 2023. (Connor O’Donovan/The Weather Network)

So what can we look at now to predict how similarly 2024 will play out?

“The indicators of a low drought to come are low water storage,” Pomeroy explains.

Remember that low snowpack that kicked off the dry summer we saw in 2023? Well, data shows snowpack in many locations in Alberta is even further behind normal now than it was in 2023. River levels were low before they froze, Pomeroy adds, indicating low groundwater levels, and he calls prairie soil moisture “as dry as you can get.”

“We could easily be in a situation where we have restrictions on irrigators, where cities have to put in mandatory water restrictions, where wildfires are again as bad or perhaps worse than last year, and where we’re fighting to preserve the ecosystems to keep our trout alive and others aline in our streams,” says Pomeroy.

“It’s going to make it challenging to decide who gets the water, when do they get it, and who can’t have it. That’s going to be a tough one for us. Canada’s never faced that before.”

On that note, the government of Alberta has already announced that it’s entering into water sharing agreements with water license holders, the first time it’s done so since 2001. It’s also recently awarded a contract that will see drought modelling developed for the province.

“We’ll have to have observations so we know what we’re managing; we’ll need to have the best prediction models to help us plan; and we’re going to have to cooperate; we’ll have to share water between cities, provinces, the industrial sector, and First Nations,” Pomeroy adds.

It’s important to note that there is still time to change course. Should we see several large snowfall events before the summer, the worst drought impacts could likely be avoided.

“The real tell will be how much snow we get, how much sticks around, and the kind of precipitation we get in that window between the last two weeks of March and through the month of April,” said Alberta Wildfire Information Officer Derrick Forsythe on the subject of wildfires in 2024.

If severe drought does come, Pomeroy hopes that it can at least be a learning opportunity.

“Hopefully this ends in a year and we get through it, and then we learn from this one so the next one impacts us even less.”